I'm breaking through

I'm bending spoons

I'm keeping flowers in full bloom

I'm looking for answers

From the great beyond...

- REM, The Great Beyond

For pictorial propositions which

so emphatically declare their maker’s name, Clive Hodgson's paintings sail

perilously close to impassive anonymity. Hodgson (b.1953), disillusioned by the figurative

painting he’d been working with since the 1980’s, has for pretty much the last

decade abandoned all ‘content’ or subject matter bar the continuity of date and

signature [1-3.]. Almost all subject matter: on

show at Arcade Gallery (London) until July are Hodgson’s still lifes, made in

parallel with the abstract ‘signature’ works since 2006 but previously

un-shown.

|

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

|

| 3. |

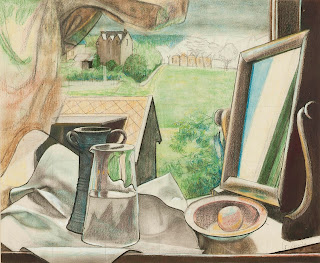

On first glance the still lifes could seem just as

blankly ‘anonymous’ as the signatures which identify them (as Hodgson’s and as

‘Hodgsons’). Their sometimes curiously neutral realism recalls that of Jean

Helion’s return to illusionism in the 1950’s [5.], a certain chalky functionalism

that simultaneously emphasizes and short-circuits the allegorical or symbolic

nature of the objects depicted (we imagine them to be significant while/because

the ‘style’ protests they are not).

Like signatures, simple still lifes are part

of painting’s furniture: pictures of apples in modelled shadow, a signature bellow,

are almost a cartoon idea of painting, are perhaps what people think of when

they think ‘painting’. The still life from 2010 which promotes the Arcade show

(it’s absent from the gallery presentation) [4.] certainly has a kind of strip cartoon feel: with its over-sized

signature, floating central image surrounded by blankness, and hatched lines

for shading (breaking with still prevalent taboos, Hodgson frequently treats

the stretched canvas more like a sheet of drawing paper) it’s something like what

happens when a famous cartoonist translates their work into paint, or is called

on to make a single-sheet museum, collector’s or demonstration piece. It reads

C. Hodgson, but it could equally be C. Schulz.

|

| 4. |

|

| 5. |

A ‘signed’

cartoon is a familiar trope of the form, perhaps an essential one. It suggests pretentions

to greatness or notoriety, popularity, respect, but also satirizes itself- the

cartoonist is eminent, if only in the funny papers. The cartoonist’s signature

is practically an implicit part of the punchline (a visual rimshot, it effectively

says ‘The End’, only more dryly), while raising (in theory) the status of the

‘joke’ to something more profound, more art-like, helps it land (literally)

with more ‘authority’. It co-opts fine art demarcations of reputation and

providence in an ephemeral and popular form. Cartoonists sign their work more

as one would sign-off an informal letter, a conversational, fourth-wall

breaking, authorial intervention; they occupy a space somewhere between

disabused everyman and auteur, which is aligned with their sense of unfussy

formal economy.

The equal

pathos or bathos of the signature, with its layered associations of skill,

craft, quality, value, identification, finish, originality, posterity, mortality and

(particularly) false or genuine modesty, goes right back to the origins of

western oil painting. Jan van Eyck, unique amongst 15th century

painters working in the Netherlands in that many of his canvases were signed (literally sating van Eyck was here [6.]),

frequently included inscriptions which ran variants along the line of ‘As I

Can’: possibly referring to the medieval literary practice of prefacing a work

with an apologia, while also punning on his own name with the doubly conceited

meaning of ‘as [only] I [Eyck] can’.

|

| 6. |

Hodgson’s

signatures frequently prompt this kind of bathetic humour- the signature, in

the abstract works at least, functioning as both setup and punchline,

decorative squiggles and autograph flimsily propping one another up (we might

think back to the many unstable arrangements of Chardin, the house-of-cards

foundations at the heart of art and and life’s pretentions). Content, such as

it is, tends to loop back on itself in a Hodgson. Indeed, signatures and simple

still lifes set up simultaneous indications towards and cancellations of ‘meaning’,

‘significance’: names are perhaps the most limited of verbal propositions, and

yet the signature is the key to Hodgson’s content- and to his complexity- while

we are rightfully sceptical about the symbolic or metaphorical significance or

potential in 2019 of apples, cups, books, tables, of whether we should take

these things for what they are and for what they are only.

Hodgson’s

signatures continue to play a vital role in the reception, inferred tone, even

character of the paintings. Sometimes the only hang-over from the abstract

works, the only identifiers that they come from the same practice, the

signatures bubble away thematically in even the most poker-faced of the still

lifes.

|

| 7. |

|

| 8. |

The 2010

picture of apple, mug and pen is stylistically removed from the majority of the

paintings on show at Arcade- only two other pictures [ 7 ., 8.] (both also from 2010) repeat the strip-cartoon, centralized and spare

composition more comfortably related to Hodgson’s abstract pieces. Similarly,

it would also be misleading to treat the still lifes as pure caricature- they

play with their own terms and conditions certainly, not to say their own sense

of potential fatuousness, but share little of the nihilism of a Guston or a

Pettibon, despite occasional formal similarities to those artists. The still

lifes are frequently more worked, less economical and almost totally removed in

colour, handling, sensibility and materiality from Hodgson’s more familiar

oeuvre- yet there are numerous thematic links which open up and enliven one’s

reading of the artist’s parallel lines of enquiry.

The signature’s numbed ability to carry meaning for

example- numbed by repetition and familiarity, but also by its own sheer

limitedness as a verbal proposition- is only reinforced by the still lifes.

Apples, mugs, pens- the 21st century office worker’s version of a

ploughman’s lunch- speak both to an older tradition of ‘studio’ still lifes (of

near-at-hand drawing implements and objects), but equally to a sense of

workplace ennui in their somnambulatory, doodled aesthetic. They come across as

pictures made at the end of the day, or to try and get started. There is a lolling

afternoon word-search or crossword-puzzle feel, of a mind looping, roaming,

drumming its fingers, while the drawing, reading and writing accoutrements again

invoke something of Guston’s insomniac studio pictures [ 10.]. Both artists tellingly depict open books

as slabs and squiggles, text dots and dashes of indecipherable Morse [ 9 .].

|

| 9. |

|

| 10. |

There is

a spinning-top or impromptu sun-dial quality to the plate, apple and seemingly

levitating or balanced pen which also recalls Rene Daniels- the Belgian

artist’s paintings of revolving LPs [11-13.], which in turn become constellations, planetary rings and satellites.

|

| 11. |

|

| 12. |

|

| 13. |

Perhaps its not a stretch to see this as a further elaboration on the

paintings’ prominent dates, Hodgson’s recurring thematic concerns of continuity,

passing time, revolution, loops, cycles, sets, increments, cut-offs and markers.

Mugs, paperbacks (propped open to mark the reader’s progress) and plastic

bottles suggest extended break-taking- and

further, breaking the day up into lunch, tea/coffee break etc. - while wrapped

flowers [14.] carry associations with special

occasions, are markers of significant events, anniversaries, or perhaps just

spontaneous gestures to break the monotony, bring in some colour. A ‘romantic’

gesture, the flowers look to be cut-price supermarket, perhaps last-minute

efforts, as yet to be properly placed or presented. They register with

complexity, as things of urgency, spontaneity, whim, or perhaps apology; things offered when words fail; along with the bottle and the paperbacks, the curtain-like form in the top right corner, they could be hospital gifts and provisions, things to pass the time, to recuperate and rejuvenate; or perhaps they

are cheap because a regular purchase, a regular decorative practice; as placed next to the water bottle they are presented in the realm of necessity. It goes

without saying that all this is entirely coherent with Hodgson’s wider body of

work (see even the star shaped, discount price-tag stencils in the abstracts

[15.]).

|

| 14. |

|

| 15. |

The still lifes are also a kind of ‘break’ from the main

project. Apples, cups, bottles, books, - the literal paraphernalia of a ‘break’,

yet equally types of objects common to the tradition of still life- are thematically

linked with a sense of ‘genre’ as a place for pause, reflection, revitalization,

even if in modest or humble terms, a resting place to take one’s bearings (whether

for maker or viewer: Corot famously saw his portraits and figures, mostly

un-shown during his lifetime, as a welcome and essential break from the

landscapes, while Diderot compared the experience of pausing to look at a

Chardin still life with that of a weary traveller who finds a shaded spot by a

dusty road). Within Hodgson’s oeuvre, these objects and

tokens speak eloquently of his own repetitions, routines, frustrations,

boredoms and spur of the moment changes of pace or direction, while extending

the abstracts’ concern with labelling and grouping, the counter continuities of

slowly-changing date and never-changing name. Indeed, the still lifes form a

hidden counter-continuity: the fact that they are all dated means that Hodgson aficionados

can immediately identify which of the abstracts were made more or less within

close proximity to them. Much of the time it seems the still lifes run at their

own pace, evolving in their own way across spare moments across the years. As

great as it is to see them collected together, it would perhaps be equally

interesting to show them alongside the abstracts, so apparently disparate are

paintings like figs. [16.] and [17.], both from 2017. (And yet the abstract has the look of a decorative

teacup …Perhaps the artist wishes to avoid such assumed correspondences).

|

| 16. |

|

| 17. |

The repetitive nature of Hodgson’s works,

and the sense of invention within the terms of these repetitions, speaks also

of orientating one’s self within

the sameness and difference of each passing day, week, year. Implied

is a sense of routine; eat, drink, shop,

remember; write-down, sign name, what

month is this...; the minor functions and mnemonics of the mind and body as

they pass through the day.

|

| 18. |

Hodgson’s pictures emphasize the shopping list

quality of the objects depicted (Untitled

(2017) practically has a corner shop window-label or café A-board feel [18.], yet with incongruous memento mori skull), laid out like groceries, provisions,

offerings. Indeed, these pictures are close to Hélion in more ways than the

neutrality/anonymity of their ‘style’. For Hélion, minor, everyday functions, rituals

and provisions take on a mythic dimension, whether sacrificial, erotic, comic, tragic,

etc., yet are at the same time emphatically about the life of streets and

rooms, life as it’s lived, objects with a history of meanings yet present,

happening Now. Similarly, for both artists, the sense

of the objects as the ‘world’ brought into the ante-chamber of the studio for

study and scrutiny completes a thematic loop with the condition of the easel

painting itself, as a portable artefact or sample brought from studio to

gallery (in their studio still lifes, its as if both Hélion and Hodgson have

just returned from a shop, an errand).

The space of the studio is ever

present- as a place of activity, reflection, isolation (romantically so for Hélion,

with his knowingly bohemian sky-lit lofts, lone figures playing instruments up

among the rooftops [19-21.]) and of

learning.

|

| 19. |

|

| 20. |

|

| 21. |

There is a slightly schoolish quality to Hodgson’s still lifes, with

their desks and scissors, potted plants and tins [26.-27.],

as if he’s been set an assignment to bring some objects in to paint (Hélion

makes the notion of ‘study’ explicit by including multiple treatments of the

subject within the one picture [22.-23.]). Oil-pastel-y and waxen, they perhaps

distantly recall the paintings of the Scottish artist (and teacher) James

Cowie, who made a handful of poignant pictures of his pupils among the art-room

bric-a-brac, the fields, future and real world visible just beyond the windows

[24.-25.], distant trainfuls of adult comings

and goings.

|

| 22. |

|

| 23. |

|

| 24. |

|

| 25. |

With

their natural surrealism Cowie’s best pictures anticipate some of the junk-shop

or ‘flea-market’ qualities of Hélion’s latter work (and perhaps share an allegiance

with the work of Hélion’s friend Balthus, albeit sanitized), whereby objects

can become suddenly anthropomorphized and jumps in scale create theatrical, table-top

worlds.

|

| 26. |

|

| 27. |

There’s

certainly a tradition of elaborately staged, transparently ‘contrived’ still

life to balance the tradition of still lifes as apparently quotidian, chanced upon arrangements-

which are obviously just as likely to be contrivances, but which make more of a

concerted effort to hide it.

One of the genre’s most sophisticated

proponents, William Nicholson can range with ease between these two modes,

frequently using/acknowledging the laboratory of the studio as a stage for such

arrangements to occur. Utilizing the gamut of painterly options, Nicholson can

wring high drama, mystery and mysticism from mushrooms [28.], books and mirrors

[32.]; a spinning UFO from a glass bowl [31.], a trans-dimensional TV

set from a Sheffield Plate [30.]; Hélion-esque eroticism from

discarded gloves, pressed under a silver casket, all locks, latches, Duchampian

spy-holes, orifices [29.]; or he can go all or nothing on knowingly

over-the-top, Gilbert & Sullivan production numbers, paintings like Emilie’s

Things [33.] or Studio Still Life [35.] which explicitly

explore the staged construction of identity, illusion, which allude to

performance, props, costume (the artist’s top hat and gloves can’t help but

resemble a conjurer’s), not to mention the studio as a kind of rehearsal space

and resource, a dressing-up box.

|

| 28. |

|

| 29. |

|

| 30. |

|

| 31. |

|

| 32. |

Across

the works is a sense of set-up and experimentation. How would it be, for

example, if a sketched-in background became a literal sketched-in background [34.]? Even a picture of a simple inkwell [36.] can continue Nicholson’s searches into mystery. Looking more like a

sounding line or plummet thrown down a watery shaft (perhaps a literal ‘well’,

the table more like a seabed, the dappled wall like disturbed water), the little vessel carries with it notions of probing, testing,

gauging- casting a line to the great beyond. (That

pen of Hodgson’s is also a kind of aerial, the ‘dish’ a transmitter or receiver…).

|

| 33. |

|

| 34. |

|

| 35. |

|

| 36. |

Hodgson

is more tentative, more suspicious than to go in for all this hook line and

sinker, so to speak. The paintings are more sceptical about themselves. There

is a feeling in Nicholson that the objects are arranged as if to catch a

glimpse of life’s mystery, that if the right combinations of mirrors and

glasses are set up correctly then something hidden might reveal itself, in a kind of homespun divination {see previous post on Nicholson}. And

sometimes there is a similar feeling in Hodgson- but tempered always by the

sense that there is nothing to be

revealed, that objects, like artworks, are vessels for our projected selves or

states, yet impenetrable in themselves. Hodgson appears careful to avoid arrangements which could seem too

emphatically communicative, significant. Certainly most of the compositions are

centred, piled, spread, rather than directed, forms are either isolated or

repeated as pattern, the space is shallow. As in the abstracts, meaning, interpretation and content

hit a wall, or find themselves back where they started, caught in a loop,

swirled around in the bottom of a mug.

The Nicholson's which are closest to Hodgson are those which qualify their own sense of import or significance, which deny or frustrate attempts toward meaning (though to complicate things, that is of course part of their meaning...). Still Life, Apples and Knives [37.], for example, throws opened and unopened letters into the balance: Apples are traditional symbols of revelation, yet the picture seems to be sceptical about the relative availability of information that might be revealed by the probing knives, lined up more like pens or palette knives or perhaps surgical scalpels, should they open up letter or fruit. Within the picture's complex interweaving of elements, so hard to put into words, is a practical exploration of both communion and communication with tactile reality, and with one's art form. Placing official looking letters and envelopes within the same visual hierarchy as the humble fruits, measuring their relative informational clarity and accessibility, measuring their relative surface and inner substance and in turn measuring those illusions against the 'skin' of the painting itself, aligning them with instruments of cutting, puncturing, exposing, putting all of this into play, Nicholson's picture embodies the ethos of still life- for the the genre is about opening up a discourse of and within silent, still and impassive things.

|

| 37. |

|

| 38. |

And while all this can sound dourly serious it can also carry a self-aware zing. Pears [36.], perhaps containing an intentionally dreadful pun, is a series of doublings, of elements 'paired' off and contrasted or complimented, elaborating on the genre's tendency to overplay the perceived correspondences between things. The double knives play a game with their singular partner across the plate, the image creating a general confusion on first glance about just how many of these knife shapes are actually knives or are in fact shadows, while the lone pear at the back casts a shadow which could easily lead one to initially register it as a pear turned away and to its side, rather than facing its round base towards us. Nicholson even adds a pseudo 'stalk' to the tip of its shadow, which is in fact a decorative leaf 'painted' (in all senses) on the plate, reiterating that it's all just painted marks anyway. And just as all these three-dimensional illusions are thrown up, the picture can suddenly flatten, the knives become the handle of a decorative fan (which could be flipped over to reveal an identical image doubled on the other side), the weight of the image suddenly subtracted. Continuing its decorative qualities, the blank background is effectively, like the plate, a decorative void on which shapes and colours are organized- while the painted 'bobs' of the fabric tablecloth in turn grant it an effective texture, make it convincingly real (utterly daring, the picture foregoes easy things like highly contrasting light or dark foregrounds or backgrounds, foregoes the safety net of a space generating table-edge). The picture manages to come across as contingent and unrehearsed, while we simultaneously register that it has been purposefully arranged and choreographed, part paint palette, part 3-dimensional speech bubble.

Hodgson's works perhaps allow us to see more clearly

certain qualities of knowing, and conceptually sophisticated humour in

Nicholson, particularly in his play with objects in studied disarray. Hodgson also

works quietly between the hum-drum and the contrived, suddenly smuggling in

skulls or improbably balanced ball-points, conspicuously ‘fanned’ or carefully

toppled piles of books. He leads us to consider the merits of more obviously

mannered, or twee, or grandiose, or ridiculous paintings, even if one’s tastes

don’t necessarily run towards such obviously contrived or over-stuffed pictures

as the more extreme Nicholson’s above, while at the same time consistently

reminding us that all painting is not that far removed from such

coquettish trickery anyway (Hodgson has stated before that he often finds merit

in certain paintings or certain passages of paintings that might not warrant it

on whole, which is helpful in understanding his own peculiar sense of painterly

'value'). As with the abstracts, Hodgson paints these still lives with the

sense that it’s a patently odd thing to do, potentially pointless, yet also

somehow obvious and inevitable- as if a still life, with its mix of modesty and

stage managing, is a natural thing for a painting to be, a natural form for it

to settle into. 'Still life' also functions as a problem for him to solve. As in the signature paintings, a series of essential elements are inexhaustibly recycled and re-processed as the set-ups are composed and re-composed- a dogged table-top experimenter, the practitioner of still life is forever involved in attempts to intervene in, or re-create, or defy systems of organization, randomness and accrual. And by the time ‘still life’ as a genre gets to Hodgson, it’s

been long absorbed that this is what 'chance' arrangements of objects look

like, just as the objects depicted are standard options with which to explore

relative types of surface, solidity etc. (though he shakes things up with

unconventional littler items, plastic bottles and wrappers, blue carrier bags,

very much the produce of a city, of shops).

|

| 39. |

Hodgson is under no illusions, and neither are we. It’s a subtle thing, but

the pictures tend to register as studied, highly conscious constructs, for all their apparent naivete. There's the sense

of someone working their way back to something which looks purposefully off-the-cuff. They

speak of a certain kind of style, of everyday pretences and deceptions, studied dishevelment. Sprezzatura. Moments of accomplished painting are allowed through, particularly the browned

swipe of an old paperback-side in which we can practically feel and smell the ever so

slightly dewed paper. However, the paintings as a whole generally carry

themselves more like paintings of paintings, or paintings of drawings, frequently finding ways to sabotage their own authority or prettiness. Rarely interested

in the details of the room in which they are situated, or even the tables on

which they rest, the objects tend to float in the centre, like an idea, a

thought balloon. In this they recall the ‘framing’ in certain Morandi’s, usually

of flowers [39.] (which also incorporate

obvious signatures). Hodgson perhaps brings in to focus some of the decorative,

even cartoony, qualities in Morandi: the signatures and the wilting, embalmed

flowers- part ice-cream sundae, part funerary urn- establishing a kind of comically

mordant, grand limpness (like Morrissey wafting gladioli, say). They often play with their own 'off-ness', the look of things gone mouldy, shriveled or curdled, on the turn. Morandi is

often seen as a serious investigator of the nature of things, matter etc., less

so that he investigates the nature of pictures per se, and even less so that he courts

a sense of deflated jollity, comically fudged beauty.

Hodgson

and Morandi operate between moments of authoritative and explorative

representation, and a fundamental sense of decoration, of ‘unnecessary-ness’, perhaps

even Roman/Pompeian ‘flatness’. Interestingly the gallery text at Arcade quotes

Manet, for whom still life was the ‘touchstone of painting’- interesting in

that Manet made problematically ‘flat’ works within the genre he apparently held

in such high regard.

|

| 40. |

Within

the limitations of still life, a painter’s weaknesses, tricks, hacks can be

exposed, or their true material philosophy of painting revealed (by its nature

the genre requires that one bring life to the inert, with little space in which to

hide). Still lifes are often a striking feature of Manet’s celebrated

multi-figure compositions, giving necessary punctuation, pinning the deliberate

inconsistencies of his space, adding up to the overall illusion, yet when isolated

they frequently fail to pass inspection: almost as if one has walked up too close to a

painted backdrop or a paper flower, the spell is broken. Manet’s brash,

virtuoso brushwork, alive to the slipperiness of the world in the larger

compositions, tends to homogenize and flatten surfaces in the smaller still lifes.

Objects tend to be centred, in simple artificial lighting and undifferentiated in texture

or painterly description, everything made with the same wet flourish; the marks

adequate, but adequate only [40-43.].

|

| 41 |

|

| 42. |

|

| 43. |

Whether

this is intentional or not is by the by- it’s part of their meaning (sometimes

failure) as artworks. I don’t think we can accept them as being preoccupied

with decoration in any meaningful sense, or with their own pictorial nature. Nicholson provides a corrective example of a truly invested, illusionistic investigation

of painted form and meaning, while Morandi more convincingly addresses the

decorative nature of the painted picture, not to say the problematized

relationships of equivalence between painted marks and surfaces, the nature of 'failed' illusion or equivalence, pictorial inadequacy as a philosophical position. The Manet of

the still lifes, whether he can be blamed for it or not, would seem to perch

forever between these two posts. (I suspect Hodgson would find plenty of things of worth within them though- one senses that Hodgson's extreme self-scpeticism is in inverse proportion to the generosity of his willingness to find merit wherever it might be hidden in others. Certainly the most problematic of the Manet's could easily be resuscitated by thinking of them in Hodgsonese, though this would require one overlook their sense of lazy complacency).

Arguably the artist's most successful still life, Manet's

little picture of an asparagus [44.]- with its repeated calligraphic

notation of veg-bud, marble-vein and cursory signature, its practically monochrome palette- is

successful precisely because it addresses his own predilection for formal homogeneity

and flatness, the intractable connection of one thing to the

other which he explores so much more fully in the complex narrative paintings.

|

| 44. |

By

contrast, Hodgson, an artist highly involved in the flatly decorative, will

suddenly tease out very precisely the form of a cup handle, or the depth of its

concavity, or the crinkle of cellophane. He’ll shift depth of field, relative

clarity, vary the balance of mark and illusion, liveliness and ‘deadness’, or

play with weight, will show books and flowers slumped next to a bottle of water, whose relative heaviness is being slowly subtracted to the point where a good breeze through the

studio window might kick it away. (Hodgson reminds us of the childhood fascinations, not to say tactile researches, that continue in the genre: the joy in filling things up, pouring them out, putting things in and out of bags, counting them, grouping them, cutting them open, rolling and piling, scrunching...).

Indeed 'weight' is another tricky proposition which still life throws up for the artist. I’ve

written elsewhere of Hodgson’s affinities with Italo Calvino, who saw the

‘systematic subtraction of weight from the world’ as a fundamental literary

project, as outlined in his Six Memos for

the Next Millennium. (The notion of ‘Memos’ is appropriate, a metonym for

lightness, quickness, exactitude etc., the tenets of Calvino’s thesis, but also

speaking to Hodgson’s sense of disabused necessity, readiness, pragmatism in

the face of inspiration or desperation).

‘Still Life’ is a genre traditionally

preoccupied with the specific weight of things, gravity, substance. So it’s a

wilfully contrarian gesture on the part an artist who frequently champions

‘lightness’ and ‘dispersal’ as painterly values; values which recall Calvino’s yes,

but equally the descriptive prose poetry of Francis Ponge, a predominantly still-life

poet if ever there was one (taking as his subject soap, candles, mud…).

|

| 45. |

Ponge, a

close acquaintance of Hélion, frequently came to blows with the painter; Hélion

annoyed that the poet should suspend the objects of his attention in splendid

isolation without giving due attention, as he saw it, to the system of

relations between objects; Ponge for his part writing on the recent pictures of

the artist’s return to figuration that ‘none of them have the slightest charm,

the slightest trace of taste’, but also that, ‘all of them have an undeniable

power’ (Ponge, 1950). Ponge, a serial re-writer and self-editor, seems to have

been disparaging of the paintings’ unruly refusals of elegance, grace or simplicity

(the isolated Cabbage Choreographies

are a late exception [45.]) , while Hélion

would naturally lose patience with anything which attempted to poetically wrench

objects from their continuum, or to rob them of their proper weight and

substance.

Ponge

attempts daring transformations and evaporations of material objects though the

sheer focus of poetic attention, matter made ‘gymnastical, acrobatical…Rhetorical?’. Which could be a very

eloquent description of Hodgson’s abstracts, but what of the still lifes? Are

they as light on their feet? No. But they posit

lightness, they measure it against leadenness. They compare and contrast

themselves with the abstracts. They are certainly not content to repeat easy strategies

of flatness, nor do they subtract substance so fully as the Manets, but accept

the challenges of taking on much more of the freight of the world whist keeping themselves afloat. Hodgson’s buoyant sensibilities

remain intact, though pushed to different extremes. The crumpled balls of paper

are a cypher for this. They suggest a notion of the pictures existing in a state just

as precarious, just as easily tossed aside, re-made, re-modelled.

For a

painter to whom ‘meaning’ is antithetical, Hodgson nevertheless interrogates a

distinctly literary balance of form-as-(super-condensed)-content. Perhaps he more

closely recalls- in visual terms, painterly terms- the elliptical ‘flash

fiction’ of Lydia Davis, in which everyday situations (often trips to the

shops, or ‘store’), frequently pass by, apparently without incident,

while seemingly having carried with them something of singular importance, if

not something entirely easy to put one’s finger on. Often ‘about’ dysfunctional

relationships, anxieties, petty jealousies and irrational behaviour, their ‘content’

practically lies solely within their formal construction, so condensed are they,

so limited in length, plot, detail etc. And part of that content is in turn

about the nature of linguistic communication, what it says, what it doesn’t have

to, what it cannot, the limits of expression and the worrisome point where our

and others’ minds and emotions take over, and control of meaning and intent is

lost. Where the sensible becomes the senseless. (I've said too much, haven't said enough...)

Davis marries form and content in ways which deal specifically with the conditions and pratfalls of linguistic expression. Her's is a language-particular literature, a cyclical literature-particular literature. If

painting deals with the silent, physical ‘matter’ of the world in ways not quite like any other

form, then still life is perhaps the most ‘painting-particular’ of genres

within that form (other than pure abstraction at the other end of the representational scale). When push comes to shove, perhaps the most authoritatively reticent of still

lifes speak most eloquently. The works of Adriaen Coorte, say [46., 47.], already intuiting all of the above pretty much at

the origins of the genre as a

distinct genre, already dealing with matter's impenetrability, with signatures, with blank backgrounds...

|

| 46. |

|

| 47. |

Hodgson has said that his

paintings could equally be landscapes or portraits- as they are always in some

sense paintings of paintings, paintings of the idea of painting- and so they might. Yet still life is arguably more

fully of a piece thematically with the signature/abstract/decorative works.

They might smuggle in portraiture- but even these are secondary ‘copies’

(literally in the Manet portrait of Morisot, cropped on a book cover [49.]), pictures of pictures (the tea/coffee

packaging depicting tea/coffee cups [27.]). These are images at a remove- and yet fundamentally based on

primary observation. With its particular weighing of distance, closeness,

remoteness, still life is in part a detective genre, in which clues are put

together to form a personality, situation or scenario, in which silent things

are made to speak, give testimony, in which subjective narratives are allowed

to colour the objective facts. Entirely consistent with the signed abstract

works, we are left to wonder how far things are codified, how much information

they might contain, or how little, how much we are projecting on their blank

surfaces.

Depictions

of open and closed books also continue the signature paintings’ notions of reticence

and (in)availability, inscription, authorship, dedication, identification. Of

locating one’s ‘self’ within things claimed. We are left to wonder how much

Hodgson identifies with the name, with these decorative marks, with the

objects, with these pictures. Or what they might say about existence in 2010,

or 2008, 2012…

|

| 48. |

|

| 49. |

Identification is a notion at

the centre of Hodgson’s work. Paintings, crudely, invite a viewer to ‘identify’

with them, while signatures can provide distancing barriers, as can

dedications, titles and so on (Hélion often plays with the nature of titles as

porous, gate-like moveable barriers or openings). Similarly, we intuit that the

painter must implicitly ‘identify’ with the painting in all sorts of ways, even

at the level of advocacy and allegiance, ‘I am for this type of painting, and will stand by it’. Hodgson also plays wittily with

the placing of the signature- the prominent printed text of ‘Colette’ [48.], for example, could indicate that the

volume is either by or about the author, whose works are a form of qualified

auto-biography in any case, ‘Colette’ functioning effectively as both title and

author credit (and as content). He also frequently underlines the signature,

mirroring the edge of the table-top with amorphous details above [50.], while they mingle with other forms of

assorted texts, notes and labels generally.

A proto-Hodgson work by Hélion, The Exhibition of 1934 (1979-80) [52.], further elaborates on this notion of

artwork-as-signature. A reminiscence across the decades, the picture finds

Hélion reflecting on the beginning of his career, then in its initial

abstract phase. On the one hand the picture measures the hermetic world of aesthetics

against a messier (not to say more cramped) world of human interactions, with

the signature a handy, anchoring wall sign [51.], possibly a mediator between the two. This sign perhaps also

by-passes the role of the woman in the chair invigilating, who is presumably

primed to answer questions about the work: her official-looking cap (like an

usherette or traffic warden, watchman, maybe even a nurse or midwife) is echoed

and inverted in the negative space left by the hanging cord of the fame, establishing a connection between the two, while her body

language is closed, perhaps silenced by the official text on the wall. But

perhaps this is a very contemporary reading of the negation of conversation

that can occur in the library-like exhibition space, the relative critical

‘authority’ of individuals and institutions, the impermeable, monolithic nature

of certain names and reputations, not to say gendered narratives of ‘genius’.

With her curiously angled ‘shadow’, she could almost be an avatar of the

artist, having cast himself back down the years, an unnoticed, Scrooge-like

observer at the back of his own party. Perhaps he wonders what she really thought

of all the ballyhoo, Turning her back on the conversation, she seems more interested in

the humble flowers. In any case she'll be there when everyone else has gone home, left with an empty room and some pictures.

|

| 53. |

An advocate of grand narrative

painting with an equally grand sense of rhythm and harmony, Hélion is possibly re-staging

the exhibition space as a version of The

Painter’s Studio: A real allegory summing

up seven (in Hélion’s case, forty-six) years

of my artistic and moral life [53.]. As with the Courbet, The Exhibition of 1934 is a kind of

preposterous picture: showing the the progression from pious devotee of

abstraction kneeling on the left, to the bustle of groups, figures and discourse, to

Hélion the contemplator of humble objects. The signature sits in the wings,

seems to ask ‘Hélion?’. (The picture is also a part-sequel to The Studio of 1953 [54.], a mid-career stock-taking over which the ghost of Courbet also hangs- though this time the visual 'key' in the bottom corner is a portable set of drawers, which allude to the picture's abundant nesting of images within images, illusions pulled-out or shut-away. The artist's avatar in this case is a compartmentalized box of tricks.)

|

| 54. |

The

signature framed on the wall of the Exhibition is a cartoony gesture,

particularly when nailed up in such an arbitrary fashion, grandiose and yet

slapdash. But it is also complex piece of a complex, recursive picture puzzle. On the one

hand it suggests the signature as the extent of the painting’s information

(with a witty comment on the nature of ‘name’ collecting), a Hodgsonian notion of signature-as-artwork/artwork-as-signature. Yet it also reflects

the wider composition in microcosm: mirrored directly below by the vase of

flowers, signature and still life are silent summations of the painting’s wider

activity. The group of figures and paintings on the wall are a kind of arrangement

or bouquet, a display, a concoction, while the depicted viewers are in turn imbued with Hélion's Hélion-ness (as is whomsoever happens to be the viewer of the painting itself), literally in the 'style' in which they are painted but equally within the narrative of the picture (they are depicted as people reacting to or 'affected' by or conditioned with 'Hélion-ness', while in fact directed by him, a sly slight of hand); the flowers and vase connect to the group's purple shadow, but it can equally appear as if the figures and paintings on the wall are being projected from them, are a magic-lantern show of shadow-figures cast on the walls (which they essentially are), as if everything can be contained, genie-like, within still-life's magic lamps, while the vase and flowers' visual counterpart of frame and name (a name being a kind of frame anyway) suggest that any picture can be further reduced to a boxed autograph, conceptually and existentially, a material registration of distinct being. It perhaps also muses on the object/art-object's ability to effect the room (this being very much the helpfully labelled 'Hélion room', while the shapes behind the signature broadly mirror walls and floor, the looped & grouped letters an extrapolation of the intertwined figures), while the ways in which picture frame and signature relate to flowers and vase are also micro-treatments of the painting’s themes

and perennial oppositions; nature and culture, abstraction and representation, the

organic and the synthetic, wildness and cultivation, speech and silence, meaning’s impossibility

and inevitability; the way independent elements have equals and equivalents

(even the apparently arbitrary, outré approach to colour in the rest of the picture is carried over into

the signature, which is needlessly multi-colored).

All of this suggests that Hélion is in some way acknowledging where he stands in relation to the painting, but also that he'll 'stand behind it', that he's signed a contract of avowal. A signature officiates at the hand-over of responsibility from artist to viewer, accepting that the painter has done all they can, that they've considered the terms and conditions carefully ('As I can') and that the work is ready for 'submission' (a kind of surrender as much as a presentation). For Hodgson, as for Hélion, the signature is a paradoxically self-effacing address to the viewer which affirms the fundamental sincerity of his involvement with

painting as it’s been left to him, as a form of endeavor and expression which one adds one's contribution to, while abdicating any further authorial control. And while it's a form of curiously anonymous 'address', albeit one intimately and indelibly connected to the maker in every way, the picture is an address without a specific addressee, a message as much as a proposition as much as a formal inquiry cast to the great beyond.

Still

lifes, like pictures, are vessels for carrying and conducting consciousness, that

ride the feedback loop of object-imprintment on self/self-imprintment on

object. The genre speaks of the blankness and silence shared by objects

and by paintings as made-objects, which can frustrate the expectation and need for

things to be easily, and probably verbally, meaningful. I've written

before that Hodgson's abstracts are like 'empty envelopes, parcels filled only

with polystyrene beans, blank messages marked only by their posting'. Perhaps

the still lives are tossed to the world (or to himself, in a roundabout way) as one one would toss a message in a

bottle, containing a slip of paper signed C. Hodgson. If only in so far as the

message is the bottle.

.

Life is only what you conjure.

- Ray Davies, Wonderboy

.