I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful

green stuff woven.

-Walt Whitman, Song of Myself 6 (A child said, What is the grass?)

Originally

staged at S.M.A.K, Ghent, now travelling on to co-organizers Pinakothek der

Moderne Sammlung Moderne Kunst, Munich, ‘Oeuvre’ is the largest yet survey of

works by Raoul de Keyser. Around 100 works spanning the 1960’s to the artist’s

death in 2012 are on view.

Though

his reputation may seem long since assured and assimilated, the retrospective

is a reminder that we should never take such things as read. The show

could equally be titled ‘Oeuvre?’- the seemingly banal, functional title masking

an implicit sense of questioning that is entirely appropriate for the artist.

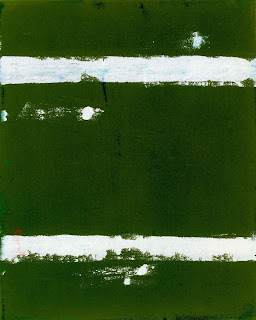

De

Keyser emerged from the 1960’s milieu of Roger Raveel’s New Vision- a distinctive Belgian mixture of pop, daily life,

suburbia- which for him morphed into a tentative abstraction. Early pictures of

sports fields with white lines painted in the grass (seen as wry, mischievous

critiques of the era’s formalism, flaunting the ‘rules’), would recur throughout

a career in which he more or less consistently explored a wavering balance of

abstraction/figuration for the next 40 years.

The

apparently hesitant qualities of early forays into more emphatically abstract

territory are often seen to betray a certain amateurism. Yet it’s a quality he

would, with sophistication, retain and cultivate throughout the decades. For

the ‘Sunday Painter’ connotation is also one of the artist engaged with

pleasure, with delight in the doing (and learning). Or, with the slightly more

desperate notion that one is painting on the Sunday as a refuge from the week.

He doesn’t merely commemorate nor strictly satirize the Good Life in the early

pictures of tents, recreational vehicles, garden hoses, window latches, but

expresses an ambivalence in regard to home comforts, which can equally be about

pleasure and banality, constriction and escape. Gampelaere Surroundings (1967), with its famous close-up of barbed

wire against pastoral field, has a typical bite to it, though the theme is

explored with more subtlety across the years. Window latches later morph,

movingly, into a walking stick (To Walk,

2012). Held up against a provisional suggestion of a country lane rendered in extreme

perspective (expressed with a simple off-centre ‘X’ in wasco crayon), the mobility

aid is both conveyer and barrier/impediment.

Similarly,

the ‘abstracts’ are often somehow wilfully domestic (a kind of precocious ‘back-room’

formalism), carried out in one or two colours, frequently on small stretchers.

There’s a stumbling sense of yearning to understand, to do-well, though in

truth it’s a radical rethink of what ‘doing-well’ might be, in pictorial terms.

This balance of real pleasure with real criticality and real expression is what

separates de Keyser from the cul de sacs of ‘painting’s impossibility’: he

wants to go on being surprised by painting’s life, not its death. And indeed,

Sunday Painting places emphasis on the activity

of painting- pottering around no bad thing.

Except of

course that works of such modest ambition- if they are modest in ambition- could easily drown in a retrospective of

this size.

The

truth is that the work is ambitiously various in terms of atmosphere and

thematic depth- and the current show does a pretty good job of showing that. De

Keyser is a tricky proposition for a big museum as he flaunts institutional

qualities of scale and thematic ‘bigness’, without demonstrably making a fetish

of smallness and intimacy.

The

various rooms are now and then chronological. The first begins appropriately

enough with the ‘60s pictures, alongside the free-standing, stretched linen

‘sculptures’ from that decade (part tent/goalpost, part upturned crash-mat)

gathered fairly close together to give a slightly period feel (or perhaps that

of a gymnasium, a ‘workout’ room). But this is a feint: the show quickly starts

to unravel into thematic groupings, while maintaining a general feeling of progression

and expansion through the decades.

The

potential problems are more to do with the sheer size of the presentation. There is a

valid question of whether a museum-scale retrospective is the best way to

experience de Keyser- frequently domestic in size if not ambition.

The

paintings are often best encountered when hung to the rhythm of less neutral

rooms, as they were when spread sporadically throughout the converted residential

interior of Edinburgh’s Inverleith House in 2015 (see below). The present show similarly

comes to life most when the white cube is relaxed. Architects Robbrecht and and

Daem- who have created several exhibition spaces for the artist since Documenta

IX in 1992- have built ‘walls’ within the walls of the central room: held up by

MDF posts and made of builder’s gyprock, their papery, flecked and pulped

surface vibrates with the paintings, letting his whites particularly sing. The

installation here is utterly sympathetic to the painter’s sense of utilitarian

construction and play (the paintings sit in a subtle grid of joints and screws,

mirroring his frequent exposal or acknowledgment of the stretcher bar). The

room, entered in Ghent through a separate door and with works darting from year

to year, is a revelation- elastically hung with de Keyser’s precise sense of élan.

De

Keyser spent a career experimenting with ‘hangs’; a constant process of staging

and photographing faux-exhibitions in his studio; leaning paintings against

walls, hanging them with blunt hook devices; putting them outside or in trees. Indeed,

the question of ‘Oeuvre?’- what it might constitute, its fluidity, how

individual works create ripples and eddies in the larger body which can support

and extend those works in turn- seems to have been central to his project.

These

questions, pertinent for any artist, are especially invited by de Keyser’s

particularly self-sustaining practice. New works are created from off-cuts, or

based on the debris left by lino-cutting, or are preoccupied with example and ‘iteration’

generally. I suspect certain paintings may have been made as gap-fillers in his

studio hangs. Not out of formula, but a push to expand formally, spurned on by

the need for something red, or longer, or more emphatically tonal, say. These

studio arrangements, obsessively documented by the artist (and reproduced in

the comprehensive catalogue),

see him looking not for total cohesion but locating opportunities for expansion.

Notions

of expansion and collection, of (sometimes eccentric) growth are reinforced by

frequent pictures that allude (however obliquely) to water, to trees. Shore from 2005 is disconcertingly

illusionistic despite/because of it’s red border, while the broken white lines

of his sports pitches are cut down to become birches. Monkey-puzzle trees

become all-over abstraction, or gestural marks against steamed-up windows (as in

1989’s November). There can be

references to their much older Low Countries tradition- as in the abstracted

windmill of Sinking (Piet)- reflective

water, flooded fields. The deceptively simple conveyance of silvery outdoor

daylight, or its filtering through shuttered interiors, recalls that of David Teniers

the Younger.

Highly

frequent images of shutters, doors, windows, blinds- devices which allow in the

light, admitting one to see out but not in- speak of the work’s air of privacy.

Even the monkey-puzzle tree, with its sense of structural confusion, is

deliberately planted as a barrier, a screen. These images perhaps speak of our

position as viewers peering through the cracks, and the dangers of getting the

wrong end of the stick, being critical busybodies. De Keyser, particularly in

his later years, is something like an old man gleefully placing questionable

objects on his windowsill to delight or bamboozle the neighbours. Yet through

time we get to know him.

‘Oeuvre’

allows itself to be summed up in its last room via a huddled grouping of small

paintings which de Keyser was working with at the time of his death. They have

subsequently been shown, and reproduced in book-form,

under the title of ‘The Last Wall’ (though the exact selection has shifted

slightly over the years).

These

particularly small works ride currents that run throughout the oeuvre- given

poignancy and testimonial status by their biographical significance. And yet

they are not summations but starting points. They can be graphic, or impasto,

or thinly washed in subtly new ways. Forms can be yet more reduced, or more

representational. They are more abject and unlovely than anything which came

before- but are buoyed by the memory of it all. And still his illusionism is

healthy. Seascape is a rag of canvas

wrapped around the middle of a stretcher, hardly meeting the edges; but these

edges become the sides of huts, unpainted canvas the sand; a single gradient of

white sky breaks off to make waves.

The

abiding image of ‘Oeuvre’, and the real summation of his career is a little

painting titled Robben 1. Swirly

lines make a rudimentary frame for a newspaper clipping of a footballer, laying

down on the pitch like a star gazer (a rare photo-collaged element).

Wonderfully scrappy though the match has been, the player falls back, surveying

the world from within his chosen arena, delighted by it all.

...

NB. This reviewer realizes that Arjen Robben, the Dutch player pictured in Robben 1, is in reality less than 'delighted'- having just suffered many near-misses in a disastrous losing match against Denmark at Euro 2012. De Keyser- originally a sports journalist -would surely have been drawn to the ambiguity of the image, its apparent carefree reverie in a moment of personal despondency. The small painting muses on the perils of missing the target, being off the mark, on the chances of luck, skill and effort coming into alignment, of opening one's self up to potential failure. Almost a secular icon, Robben 1 is about being involved in and alive to the complexities of art and life, to the field of human endeavor.

.