But the picture

does contain elements of ambiguity. Painted shadows act as autonomous

characters, the figures’ shadow becoming a composite, either an image of their

reconciliation, their fleeting union/reunion, or something more threatening; the lamp seems to

scuffle with its own shadow, spinning around and either dancing with it or almost throttling it, an elastic area of looping

shapes in the otherwise sedate composition. The sailor-man smiles, but this

could equally be a scene of struggle, spurned advances, the woman hemmed-in

visually by the post on the wall at the edge of the frame. She’s ran out of

space and out of time, whatever the situation, reached the end of her

enclosure. For a picture with a lot of blank, generalized space, each element

is cropped with little room to breathe. The sky is a postage stamp,

the strong horizontal of the wall curtailed by the portrait format, the lamp

pushed-up against the post. The trees - which are given a relatively generous portion - are equally fenced-off. Even the viewer crowds her: we’re already

crossing the street, the cropped pavement suggesting little distance. The eye

becomes just as trapped, caught in the web of pictorial elements, or circling

the loop of hands and shadows at the centre- playing out her dilemma optically. The 'characters' waltz mechanically, like figures that emerge on the hour from clocks in town squares.

Eckersberg presents a world of limited options. The figures are

like Westworld automatons, background characters programmed to repeat

their parting routine. Or: they are like people as seen by such

automatons. People repeating their various circuits, their coded behaviours.

Pictorial behaviours, even.

|

| 2. |

|

| 3. |

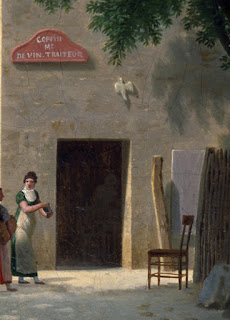

If they look like characters from an

illustration/demonstration, that’s because they partly are. Eckersberg studied under Jacques-Louis David for a time, but it was works like Gerard de Lairesse’s The

Great Book of Painting (1707) [ 4.] and Erdmann Hummel’s Free Perspective

Primarily for Painters and Architects (1824) that seem to have really

caught his imagination. They inspired him to publish his own Forsøg til en

Veiledning i Anvendelse af Perspektivlæren for unge Malere (An Attempt

at a Guide to the Use of Perspective for Young Painters) (1833) and “Linearperspektiven, anvendt paa Malerkunsten (The Linear Perspective Used in the Art of

Painting) (1841): containing a series of instructional etchings perhaps more

beautiful and haunting than the majority of his paintings. Rather than simply

set exercises with rudimentary buildings, trees and figures,

they present fully realized environments, a rolling backdrop of walls, ladders,

barrels and lampposts, all of them lit like sundials or geometry models. The

Sailor and his Girl seem to have started out as one of these perspective

studies [5.], and many of them take place in the same virtual world, a endless

stretch of wall and cobbles punctuated by lamp posts.

|

| 4. |

|

| 5. |

The etchings

make the paintings’ lines of construction explicit, but they also make clearer Eckersberg's pictorial sensibilities, reveal his true artistic sensibility, such as it is. The Garden Wall [2., 7., 8.] might as well be a kind of extended signature, the man up the ladder carefully adding a letter 'E' to the post, leaning on a mahl stick, leaving a neat monogram on a tidy universe. The ladder itself is an image of construction, or construction-as-revelation, illumination (only he can see over the garden wall), propped and propping. He's signing it because he built the wall, constructed the image, made the world. Made the world sensible. Even the lamp is a kind of 'civilizing' of light, a rationalization. There's perhaps a chain of association between this, the sunlight, the picture-as-light-box; a feeling that what we're looking at is sort of deep picture code, deep painting code; like he's ran picture-making through a prism. In another image the figure is ascending the ladder to fill the lamp with oil, to maintain the world's visibility. These tools of perspective, of picturing, Eckersberg suggests, are not just handy tools, but are philosophical anchors: weights and measures to be used in grasping the holographic procession of the visible world. A world, he concedes in this rare candid moment, which is unavoidably imprinted with his own self.

Like Adolphe Monticelli's A painter at work on a house wall (1875) [ 9.], the painter literally creates the world, the world is him, the picture is signature.

|

| 7. |

|

| 8. |

|

| 9. |

Hmmel’s book on

perspective had arrived at the Danish Academy library in December of 1830,

around the same time Eckersberg moved away from history painting to scenes of

everyday life, a confluence of high rationality and the hum-drum of street

bustle, which can descend into calamity at a moment's notice. Langebro,

Copenhagen, in the Moonlight with Running Figures (1836) [10.] was painted around

this time, while the almost folk-art View Though a Doorway of Running Figures (1845)

[11.] completes something of a circle with this and the almost objective works from early in his

career (pictures like A Courtyard in Rome (1814) [12.]).

|

| 10. |

|

| 11. |

|

| 12. |

There’s a weird back and fourth across

Eckersberg’s oeuvre. Pictures from the Grand Tour seen from oddly objective

viewpoints (recalling the contemporary sketches of Thomas Jones, who was in Rome around the same time, though it's unlikely Eckersberg would've been exposed to Jones's private studies), carried out simultaneously with Neo-classical history scenes, their relatively objective realism returning intermittently alongside stilted religious and mythological subjects, scenes of harbor-side wasteground alongside conventional marine battles. His portraits and nudes fluctuate between blankness and adoration, analytic realism and idealization; the nudes depicted frankly as models one minute, then given copy-paste Arcadian landscape or plush interior backgrounds the next. There’s also a large body of simulation-like

landscapes, marked by a recurring sequences of fences, posts and arches that

reign the world in, populated with stock figures that finally emigrate to the strange storybook world of the genre scenes.

|

| 13. |

For all their frequent coldness and

calculation there’s a moving sense of an intelligence trying to assess the best and

most truthful nature of picture-making, the best of all possible artificial worlds. The paintings are either elaborate constructions,

almost absurdly orchestrated, or practically randomized attempts at accuracy,

veracity, honesty [13.]. There’s a mix of intelligence and naiveté, a

refusal to give-in to a certain manner or loose expression; he wants to get it

right. But he treads softly even in asserting rightness. The result is a kind

of impersonal anonymity (and humility, for all the that the pictures

represent a problematically self-satisfied, entitled, Euro-centric universe).

|

| 14. |

View from the Lime-kilns in Copenhagen

(1825) [14.] is a typical Eckersbergian paradox. On the one hand a functional

depiction of a functional space, it also gets caught up in the play of ships,

posts, and sandy scrub, which becomes a kind of formalized, geometric analogue of the motion of the waves: a clockwork ocean that becomes like the wheel of a

music box or a pianola roll (there are times where Eckersberg’s pictures look

like they were programed by such a device, ‘Painter-Pictures’), a sequence of horizontals and verticals complete with

diagonal winder; like a fairground amusement, it feels as if the post could be

cranked to make the waves and sailboats move to and fro. For all their apparent

certainties in perspective and societal-pictorial organization, the paintings

betray a subtle anxiety about the knowability and unknowability of the world,

sitting on the fence between the mechanical and the phantasmagorial universe.

Eckersberg’s pictures often draw comparisons with Kant. But without getting into all that in any kind of reductive way, paintings like View from the Lime-kilns muse on the limits of the knowable world on their own terms- looking out at the ocean as the ships disappear on the horizon.

|

| 15. |

|

| 16. |

|

| 17. |

Part of what's interesting about Eckersberg is that he's so hard to classify. The painter who, through his influence at the Academy, brought plein air painting to Denmark, who introduced daylight life-classes, who brought internationalist practices to isolationist, Golden Age Danish painting while remaining still somewhat closeted within it; who became a bore to his students, preaching the gospel of perspective, sending them off to look at nature while handing them a steel ruler on the way out. His paintings can seem utterly dated, even for when they were made, but can equally appear to stand outside of time. Possibly because dated. A radical within his context, in a way it's his conservatism that makes him interesting, and perhaps aligns him with some surprising counterparts.

A little dose of conservatism in

the right measure can be its own kind of radicalism, after all. In that, Eckersberg's a

little like the late Stephen Mckenna: an artist similarly hard to pin down.

McKenna is somehow 'academic' whilst being utterly non-acedemic, studied

without being stuffy, intellectual without being reductively 'theoretical', his

pictures like the work of a Sunday painter who read classics at Oxford (the

truth is they were made by a Sunday classicist who studied painting). They wear

their deep knowledge of the European tradition on one sleeve, and, if not quite

their heart, at least a kind of obstinate determination to remain complex and

smart and delighted on the other. They are about being in rooms and parks and

cities, but they are also about the ruins and follies of civilization, the

melancholy of the cultural memory-bank, part children's book illustration, part

postmodern pastiche. Ridiculously pretentious, but equally totally disabused

and present, giddy on the world. A determined naivete meets and matches an equally determined

sophistication. Emphatically cultured and cosmopolitan (Eckersberg was pretty parochial by comparison), they are equally happy to defy good sense

and good taste (before his death, McKenna designed his own retrospective as a perverse salon

hang, a last gesture of fogyish cool). Cultivation and civilization are held up as ideas, though always with a

question mark in the corner. Measuring ideals against instances, the pictures

explore what it means, emotionally, psychologically, to be the heirs of a

classical tradition living in an imperfect word with a strong sense of what it

should or could be [18.-24.]

|

| 18. |

|

| 19. |

|

| 20. |

|

| 21. |

|

| 22. |

|

| 23. |

|

| 24. |

Like the majority of

Eckerberg's pictures they lean toward the impersonal, the anonymous, the

simulated. They are equally caught up in the play between the idea of the thing

and its appearance. Where they might be said to diverge is the extent to which

McKenna is invested in ambiguity; but also, really, in love. Or at least, where

they place and how they express that love, what we might call their humanity.

Eckersberg was certainly 'in love' with the world, laying on his back for hours

up on the academy roof, gazing up at the sky so that he could better understand

the movement of clouds. But it's a scientist's love of the world, perhaps,

where metaphor and poetry don't quite have a place. Which is not to say that

metaphor and poetry aren't present: they're often just clunky if they are, or

speak loudly by their absence, or by their clunkiness. Or they're there as

a concession to what pictures are generally like- if pictures are things that

generally contain elements of ambiguity. Or they're weird, rogue

elements, like the shadow and the lamp in A Sailor, or the way the

gate in Mariahvile in the garden at Sanderumgaard (1806) [16.] looks like a

portal to a parallel, sunny world, to Oz's yellow brick road; meaningless in

themselves but crucial to how we react to the pictures, that contribute to

their compelling strangeness.

Certain rules, generic or pictorial conventions or simple mathematical organizational principles, seem to be making decisions for him. As if his hands are tied. (When

his pictures become compelling it's often, as in A Sailor, because

this pictorial inevitability resounds off the thematic inevitability). It's hard to tell how much ambiguity is encouraged, how much of it he tolerated, or how much he simply didn't intend. It's also hard to tell what he put into the pictures because he thought it should be there: in the landscapes particularly, with their pergolas and paths and lawns, and their rowing-boats and their ducks and swans, it's as if an A.I. thought to itself what do people like, what would they like to see in this picture?. What would a person find pleasing? With Eckersberg it's like they're pictures of someone else's Arcadia, not his.

|

| 25. |

|

| 26. |

Ironically the landscapes' sense of supreme understanding, of nature tamed and a world in harmony, cannot help but be seem disconcertingly perfect. They are often ridiculously idyllic, like pictures from decorative tea trays or table-ware. Like McKenna, he often returns to the image of the park or the formal garden- a hybrid of the natural and the artificial, an imported Arcadia- of the picture-as-park. A playpark where things can be uprooted, transplanted, choreographed.

|

| 27. |

|

| 28. |

Nearly

all Eckersberg's pictures of residential or public landscaping have an

ornamental pot or sun dial dropped in

to catch the light, rendered impossibly clearly and often partnered with a human counterpart. As with the lamp-post and the Sailor, they're thrown into visual relationships, the inanimate objects somehow endowed with a sense of intelligence, or at least consciousness, greater than that of the humans. They seem to watch over the figures. In Summer Light in Sanderumgaard (1806) [28.] the crouching woman becomes a kind of sundial herself [29.], while the stroller in Source Hut in Sanderumgaard Garden is eyed by the building as he passes by, as oblivious as the drifting cloud above [31.]. (Eckersberg might be said to break away from conventional pathetic fallacy, wherein it's typically nature that's endowed with human feeling, instead finding an 'aliveness' in things like objects, buildings and ships which outweighs that of the figures). Lamp-posts particularly are placed as onlookers- in View from the Three Crowns Fort (1836) [17.] the lamp takes the place of an observer on the lookout point altogether. They are in some ways substitutes for Eckersberg himself, these silent sentinels, almost like he subconsciously aimed to be a kind of impassive lamp or sun dial, receiving and recording and perhaps even projecting, but passing no judgement. He seems to have at least felt some kind of affinity with them.

|

| 29. |

|

| 30. |

|

| 31. |

The early painting View

of Møns Klint and the Sommerspiret (1809) [32.] plays out this drama of

observation and passivity, the woman turning away from the precipice, the young

man imploring her to look, the old man sitting watching, an analogue of the

picture-viewer. But the older Eckersberg would probably dispense with the

elderly figure on the right. The bench would be enough. Remove him and the feel

is consistent with late Eckersberg (there's an instructive watercolour that

already suggests as much [33.], dispensing with the figures altogether, the backcloth doing the actors' job for them). The Sailor

and His Girl are a late career re-capitulation of this image. They're both images of

fenced off nature, containment, and an imploring gesture towards the unknown; the

man trying to make her see, to impose his vision; to take possession of the

image/narrative, to master his environment/relationships. In Eckersberg, the

attitude of the picture is the attitude towards picturing, is the attitude

towards humanity, is the attitude towards the world. And it's not

without its problems. Perhaps revisiting this harmless scene about man's

mastery over the sublime he saw within it the romantic dynamic of possession

and control. It's little wonder that in both pictures she doesn't want to look.

Many of these early pictures seem like attempts to establish a coherent position on picturing as allied to his notions of perspective and construction, of 'mechanical perspectives', mediated perspectives. Figures that later become sundials and lampposts look through telescopes [35.], or compare the map to the terrain [34.]- implicitly questioning the relation of picture to world.

|

| 32. |

|

| 33. |

|

| 34. |

|

| 35. |

|

| 36. |

The figures themselves are often more decoration than anything, of the same order as the mechanical ducks and swans set to do laps of his ponds. It's a stone's throw from artificial environments to artificial beings in any case, and the 'people' sent in to enjoy the environment can equally look like they were sent in to maintain it, like they're tending the illusion. It goes back to the clockwork nature of the Sailor and his Girl, lights on but pretty hard to tell if anyone's home. Staffage figures seen up-close.

|

| 37. |

Eckersberg's figures are generic, even among themselves. And that genericism is only compounded in the later genre scenes, where generic crowds of generic people walk or run down generic streets to or from some unidentified, generic calamity [39.]. It's often said that these pictures are about the mystery of what's happening off-screen, why the figures are running. But I don't think that's quite it, so much as they're about the mystery of why we, the looker-picturer, aren't.

They're somewhat like misplaced allegories, or emblems that have lost their text; the people of indeterminate age and class, in a functional, multicoloured uniform; the thematic content somewhat about fate, the 'incident', or disruption versus the onward march of daily life; a change in the weather, or single-mindedness, or cross-purposes. But only inasmuch as pictures can generally be about these things. They're close to similar pictures of McKenna's [37., 40., 41.], people in procession, or ascension, or at toil, or at loggerheads; inasmuch as people are generally to be found participating, getting along or not getting along in such ways. They remain medium-cool. Specifics of personality or situation are effaced, patterns of behavior reduced to cooperation or collision. Motives remain either base or unfathomably complex. Unsure which.

|

| 38. |

|

| 39. |

|

| 40. |

|

| 41. |

It's a reduction of human affairs to plot rather than story: and so their ghost-subject is story. They might partly be said to be about 'narrative', its comforts and lies another handy construction to go along with lampposts and linear perspective. In a roundabout way they have something to express about 'humanity', because they pretty much dispense with it, or at the very least treat it as something of a remote concept, some unknown quantity. And knowingly or not, they critique the notion of 'genre' generally, and 'genre painting' specifically: 'genre''s compartmentalizing of the world an anathema to Eckersberg's objectivity, but at the same time reflective of his affinity for 'constructs' and systems. Their folksy, storybook qualities prod at the notion of storytelling, narration, commentary and comment. For all that they're close to allegory they are reluctant to coerce the world into allegorical shapes. It's something of a cliche now, particularly since the invention of photography, that the picturer cannot both picture and participate, or that picturing is its own compromised participation. But Eckersberg seems to have come to terms with his decision to sit-out pictorial 'participation' in these later works, to withhold judgement and to remain on the sidelines while the world walks past his door. To that end, Figures Running is one of his most revealing images, the world a play of light and colour across a screen. And also a thing he made up.

Eckersberg's pictorial ambivalences perhaps share less with McKenna (a skeptical believer when it comes to grand narratives) and more with the eccentric works of Louis Michel Eilshemius, another sophisticated naif. His War (1917) [42.] is a great picture on murder because it reduces the subject to blunt facts: man shoots man, he dies. The birds fly off, but not out of any moral indignation, not due to any rupture in nature: the gun made a noise. It's neither a picture of victory nor of tragedy. It's overtly comical in a way that Eckersberg never is, but, details of handling and style aside, it's not unthinkable that he might have produced a very similar treatment of the subject. It's common criticism that his religious, historical and mythological pictures are crushingly, comically inert, but in many ways that's the point of his art. Melodrama or flair would only distort the facts. And, crucially, would seem overly keen to push a certain 'meaning'. Things and actions in the Eckersbergian universe have a compromised capacity to mean, or to be made to mean. And again, in the their roundabout way, they end up being about our relationship with meaning. Perhaps even the hermeneutic or ethical void left by rationalist secularism. Intentionally or not, they posit the idea of meaning and meaninglessness.

|

| 42. |

|

| 43. |

|

| 44. |

It's not all doom and gloom. For all they submit their pictorial/personal agency to cold arithmetic there's a hint of deadpan comedy to them. Particularly the ones with the frontal, full-figure framing: very quickly established by silent cinema

as the best format for physical comedy, as it allows not only the maximum amount of figure and a good amount of its environment, but because it also presents the human comedy as framed by an orderly universe, individual calamity framed by societal structure. It places disaster in context. The disruptive figure either wanders into the frame, upsetting the apple cart, oblivious to the chaos left in their wake, or the frame follows them towards their impending miss-hap.

As much as they are emblems of order and understanding, Eckersberg's figures up ladders are also primed and ready for slapstick (though the Sailor also looks like he might break into song). There's a Keystone Cops quality to his running figures, all stampeding in the same direction [46.] (having sacrificed their individual agency to the collective will). Eilshemius's War is very close in sensibility to Chaplin's The Gold Rush (1926) [44.] or Buster Keaton's The General (1927) [43.]. You can practically hear the piano.

|

| 45. |

|

| 46. |

Crucially though, Eilshemius is much more various in handling, tone, emotional range and pitch, even. War is one thing, but then there's a picture like American Tragedy: Revenge [47.]- a little arms-flailing melodramatic yes, but there's nothing quite so arch in the mood or mark-making. There's something of an attempt at real pathos, or at least the notion of pathos. It's hard to judge.

Eilshemius is a little more like, say, Derain, in that he's alive to the effects of micro-adjustments in handling and pitch, composition, the possibilities within subject and variation, mining the picture data-bank. For Eckersberg, it's as if there's only one real way of representing a scene, which is the best and most truthful of all possible ways, with any traces of 'touch' on the surface erased for the sake of clarity. But then again, this is to be insensitive towards the re-emergence of certain motifs throughout his career, correspondences in subject and form that zip from period to period. As if he's methodically trying to distill some essential version of a 'picture', a 'painting', or the most appropriate compromise between realism and picture-ness, between painting and world.

|

| 47. |

|

| 48. |

|

| 49. |

With their painted-on frames and decorative borders, Eilshemius's pictures are much more explicitly about construction and artifice, vantage and viewpoint. More explicit, but not inconsistent with Eckersberg's preoccupations. Eilshemius's figures are also (like Eckersberg's) more often than not cyphers rather than 'people'; his attitude to them similarly ambivalent. He famously said a true landscape is incomplete without a naked lady, but painted just as many with as without. And when they're there, they're hardly more than the idea of a naked woman, the idea of naked women in pictures.

|

| 50. |

|

| 51. |

|

| 52. |

|

| 53. |

|

| 54. |

Eilshemius's Spaniard Dreams [55.] is startlingly close to one of Eckersberg's instruction manual drawings, Southern Courtyard with Farmer, Vineyard and Colonnade (1838/40) [56.]: the rakish stance of the figures, both leaning in the sunlight, decorative creepers hanging over each wall. Obviously the style of dress would've been more immediate to Eckersberg's everyday world, more dressing-up box to Eilshemius. But there's still a 'stock-ness' to him, he's still something of an archetypal 'worker' figure, in all senses of the word, a functional, rank and file painterly 'type'. A painting drone. He's really there to interact with the barrel, in the same way that Eishemius's more buccaneering character is there to interact with frame, signature and floral decoration. He's leaning there partly to investigate dash and flourish against the functional wall and simplistic frame. It goes practically without saying that the picture is also a none too distant cousin of the Sailor and his Girl, the 'Sailor' with his jaunty hat and ribbon another programmatically 'colourful' character, ripped from the same staffage album.

|

| 55. |

|

| 56. |

Running Spaniard Dreams through Google's reverse image-search, the closest image results are early 20th century greetings cards [57.], the closest search term 'picture frame'. Which is pretty good for an algorithm, and pretty representative of artificial intelligences' succinct approach to criticism. Encountering Eilshemius's curious mix of genericism, literal-mindedness and dogged specificity it seems to recognize something of itself.

Run Eckersberg's

drawing through, and the suggested search term is 'visual arts': but the images

are overwhelmingly architectural studies [58.]. The system seems to know

it can discount the decorative figure, or lump him in with the rest of the

structures, seems to want to express that it's a work of art closer to

technical information. This is a facile exercise, sure, but it's hard not to

see even the workings of this relatively simple algorithm as something like a

gesture of mechanical interpretation. A bare bones critique, minimal text and a

series of illustrations. Between the two an interpretation. More importantly,

and more convincingly, it's hard not to see in it parallels with how Eilshemius

and Eckersberg work through the sundry pictorial options available to them;

which is not altogether 'personal' or 'expressive' in the conventional sense.

Intuitive perhaps. But also deeply aware of convention, category, of an

existing painterly software. The wildly off-the-charts Eilshemius, self

proclaimed 'Transcendant Eagle of Art, Mightiest All Round Man, Supreme

Womanologist and Marksman, Wonder of the Worlds, Etcetera', went as far as

to publish a pamphlet, Some New Discoveries! In SCIENCE and ART (1932), in

which he recommends several picture-making strategies which circumvent the need

for authorial intention, invention or expression (along with handy tips for full movement of the bowels, among other things) [59., 60.]. But it's important to note this as probably something of a self-parody (for all the gaucheness, Eilshemius owed his facility to conventional training), and that neither of these artists take a totally arbitrary approach to image and composition, as in the work of Gerhard Richter for example. They certainly never negate composition, in its broadest sense. For all their impersonal qualities they're devout believers in pictorial construction. They're always reaching for something.

|

| 57. |

|

| 58. |

|

| 59. |

|

| 60. |

Eckersberg, really, is a bit like a precocious AI obsessively making paintings. All three artists- Eckersberg, McKenna, Eilshemius- are, in their way (perhaps we might say Eckersberg aspires to be a kind of unbiased, pictorial-intelligence). Competent and clumsy, by turns, synthetic, strangely impersonal or hard to fathom, hard to quite get a firm hold on (all of them somehow finding something of a 'common denominator' in the 'naive' art of Camille Bombois [61.]). Seeing the poetry in the proposition, the melancholy in mathematics. Slightly stuck, after a while, on the degree to which the world is like pictures or pictures are like the world; perhaps concluding, on further reflection and to varying degree, that it might be wise to treat pictures as pictures and world as world, though the two may occasionally pass the time of day, tip the hat.

|

| 61. |

Of course what real digital 'painting generators' do is regurgitate amorphous bits and

pieces of existing images, generalized indications of form and light as learned from the picture data fed through. No program has really managed to make a resolved original composition of its own. But there's a way in which Eckersberg's pictures look like what might happen if an AI fully learned the mechanics of perspective, composition, colour, lighting, if it read up on pictorial symbolism and meaning, genre, picture code, and managed, despite itself, to produce occasional images hard to shake. Hard to shake and indelible because they self-reflexively self-echo these notions.

We might assume that if an AI sat down to make a drawing or set itself up with easel and palette that it would be something of a slave to reality. Or it would be something of a slave to assimilated visual history. Or it would make some form of concession and compromise between the two. Or it would be hamstrung by the sheer range of contradictory approaches available to it. We might wonder where it would begin to - by hand - reproduce reality two-dimensionally. What reality? How much and which parts of it? From what perspective and to what end? The AI is, by definition, a thinking thing, not an objective lens. And so there would be a subjectivity revealed in even its most purposeful attempt at impersonal accuracy. (Conscious and self-conscious thought allows us to see perceptively, if not clearly.) On the other hand, the AI is supposed to be representative of thought freed of history and prejudice, uncoloured and unclouded, and so reluctant to suddenly use the history of visual representation as a crutch.

In this predicament perhaps the AI decides to say what the hell and begins the picture anyway, groping and stumbling forward. And maybe it even decides to make the picture in some way about its predicament. And maybe it decides to try and see if it can't find a subject or a way of framing that subject so that the predicament becomes a way of understanding and engaging with the world generally. It might decide to include the window-frame as well as the view. The fence and the field. It might consider mediation generally, or remoteness, or isolation, or adoration, or interiority vs exteriority, or something simple like scale, or light, or any other number of things while it's at it.

Fighting fire with fire, it tackles consciousness with consciousness. Painting consciousness. We imagine the AI to be so doggedly tied to reality or to convention that the pictorial results of its endeavour would be inert, dull, lifeless. But would the self-reflexivity of form and content, observation and invention in painting be a stranger to the Artificial Intelligence? Or would it not delight in a feedback loop so like the structure of its own mind?

|

| 62. |

Self-reflexivity and metaphor are an odd prospect in Eckersberg. On the one hand he rejects meaning to some degree, rejects metaphor, but it's still there. And when it is, it's in the form of visual metaphors for or distant metonymns of perception and construction, art and artifice, which we see time and again. His intelligence is emphatically a pictorial intelligence, he sees pictures as intelligences.

He returns frequently to the image of a courtyard, (sometimes agricultural, sometimes more like a set of stables, sometimes adjacent to a botanical garden or a vineyard) when dreaming up his perspective studies, a kind of architectonic crucible set up for the interaction of various pictorial elements. It presents an eloquent expression of his approach to picturing, with its confluence of construction, work, nature; within the courtyard, which is a kind of frame, are people tending, carrying, mending, sharing the burden of their (picture) environment. In the perimeter walls open gates and apertures, through which we see the same figure carrying out the same task from a alternate perspectives; effectively the same man hammering a nail in the wall from the left and the right, from near and far. Looking for all the world like he's putting a picture up [62.].

The courtyard, the frame, the picturing-brain, becomes a propositional space, with a series of trapdoors and shutters opened and shut at will, reshaped and shifting in structure at will, but still bound by certain laws and rules. It's continued existence as a stable space, a stable visual economy, depends on certain codes and contracts, certain agreements of construction and cooperation; between picturer and world, between picture and viewer. The back and fourth keeps them running.