Now is life very solid, or very shifting?

-

-Virgina Woolf, Diaries.

In a way, Sickert had always played the

impartial observer- but that was only ever partially true.

Certainly, in terms of composition, he

tends to be quite distinct from many of his peers- even from Nicholson, who is

just as interested in the complexities of viewpoint, vantage, oblique angles,

temporal registers and so on (if not more so).

The difference between Sickert and

Nicholson, say, is that Nicholson looks at the subject, or up or down at the

subject, or across at the subject, or is in the process of turning to look at

it, his attention caught or held: while Sickert is already looking away.

It’s a very subtle distinction, partly

based on elements of composition, partly to do with the submission of detail,

and party as a kind of temporal register- we feel we are already moving on in a

Sickert (or, at least, in many of them).

|

| 50. |

To go back to The Front at Hove, it is typically bunched up to one side- our gaze

moving away as in the famous ‘embarrassed camera’ shot in Taxi Driver (49.) In Reflected

Ornaments we can almost see a ‘pan’ away from the subject, as if the true

subject (whatever might be taking place in the room) has been censored, is

off-camera. Even in seemingly casual, breezy pictures like Ethel Sands Descending the Staircase at Newington (50.) we feel as

if we’ve glanced up, perhaps have stolen a glance, and have begun to look away

(for whatever reason- recognition, familiarity, secret adoration,

embarrassment); everything leads our gaze away from the figure as much as towards

it; our eyes slide back down the banister, where light and dark are more

dramatic and more concrete than in the top portion of the figure, or are drawn

to the sunburst clock, the rat-tat-tat of the posts and steps, the punctuation of

the picture frames, all of which also ‘plot’ her path, a series of vertically

descending bumps or notes on the stave. And again, it’s a favourite Sickert

motif, the curling, unravelling swirl off to one side- like a curtain sweeping

to reveal or conceal, to change the scene- just as the subject is one of

arrival and departure, transition, moving perhaps from privacy to company, from

a room of one’s own to the space of the viewer, a possible jolt of recognition

(Sickert often pictures interiors as thresholds, vestibules, transitory spaces,

framed by doorways, blinds, curtains, staircases (51.), iron bedframes; rooms,

like pictures, are hoops through which life passes. And again, the seasonal

late-summer/early autumn atmosphere to the light blown in through the curtains,

the fiery ornamental sun-clock add to the notion of passing time).

It’s an approach to the sensual-psychological world of moments moods and images that recalls Woolf’s The Waves, her 1931 ‘play-poem’ almost entirely composed of scenes or atmospheres or situations which seem to evaporate and shift before they’ve even completely materialized- like waves, coming into view and dissolving just as we latch onto them- the play of the world as it comes into a specific focus and once again recedes back into the homogenous, continuous whole. Sickert (as with his particular lineage, Manet, Daumier, Degas) zeroes in on the moment, the transition of the moment, its dispersal and collapse, its perpetual emergence: the perpetual emergence of the perceivable world, fenced-off in discrete pictures.

It’s an approach to the sensual-psychological world of moments moods and images that recalls Woolf’s The Waves, her 1931 ‘play-poem’ almost entirely composed of scenes or atmospheres or situations which seem to evaporate and shift before they’ve even completely materialized- like waves, coming into view and dissolving just as we latch onto them- the play of the world as it comes into a specific focus and once again recedes back into the homogenous, continuous whole. Sickert (as with his particular lineage, Manet, Daumier, Degas) zeroes in on the moment, the transition of the moment, its dispersal and collapse, its perpetual emergence: the perpetual emergence of the perceivable world, fenced-off in discrete pictures.

|

| 52. |

The picture has a slight echo, possibly, of

Manet’s Le Chemin de fer (52.) - with

its chess-move exploration of looks met, suspended, withheld, of solidity and evanescence,

of matter and transience. In the Manet, a startling amount of nothingness is

allowed to occupy the frame, the girl’s attention held rapt by the

unquantifiable play of light and steam as it passes the gaps in the solid rails,

a puff of stilled time (her pose is also that of someone holding an easel painting up to hang on the wall)- just as in the Sickert we watch for the play of light

and dress as it passes the posts, fragmenting the image, speeding it up, flickering within the grid. In the

Manet we feel ourselves slowly drawn to the white emanation at the centre,

while in the Sickert we also feel the pull of the dark bottom portion, which

seems to draw the white dress down- the longer one looks the more the lower

steps seem to ripple like murky water, the interior staircase more like a moss

covered jetty, the pooling banister becoming a series of watery highlights

(transposing again the relative solidities of the top and bottom portions), a

setting more like that of Daumier’s fleeing mothers and infants/laundresses on

the banks of the Seine (which themselves may have been partially influenced by

his neighbour, the painter and photographer Charles Negre, who would often add

pencil hatching to his negatives in order to tone down the city backdrop behind

his photographed urchins and street-types (53.). Negre was also known to apply

thin layers of oil to his prints, in order to use them as ‘sketches’ for

paintings. Concerns with attention and focus, viewpoint, view-finding even, are important for all these artists.).

|

| 53. |

And

still we don’t look at the woman, but seem to be looking away, for we know

where she is going, we know she’ll pass the brightest point on the turn of the

banister, that she’ll walk down into shadow. Everything is set up for her, and

we’ve taken everything in (Sickert often plays with the notion of

‘registration’, the speed at which an image is recognized, at which it unfolds

or how much of it is allowed to become clear). For Sickert, part of the wonder

of pictures is how they remain suspended, yet go on spooling, elaborating on

their own and by their own means (or not), how they continue to ‘move’ and at

what specific speed. We sense Sickert turning away from his ‘moments’, perhaps because

he already knows pretty much how they’ll play themselves out, how they’ll fall

apart.

Such compositional devices also create a much

more complex sense of our relationship to the subject. Rather like an

unreliable narrator, we sense the ‘looker’ (which is Sickert but which is

really ourselves) to be somehow obfuscating either the full picture or their

full relationship to the picture/subject, or that audience/narrator possess privileged

information, a sense of the characters’ trajectory or context that they

themselves aren’t privy to (perhaps also that such concretized moments are a

kind of slip into genre, into types of scenario, in the way that life can be

pulled inexorably into habits and constructed conventions or continuities of behaviour as

much as pictures can, which Sickert both acknowledges, subverts, and

problematizes. Sometimes it’s almost 'genre' as dramatic irony- the subjects

caught, unawares, within moments of ‘picture’). The viewer becomes a character

within the play, and we are faced with our own relationship to the subject as

much as we are faced with Sickert’s (do our eyes busy themselves with clock and banister so they don't have to catch hers?).

I think part of the atmospheric richness

and emotional complexity in this kind of looking and looking away, this kind of

elision in Sickert is what appeals to novelists like Woolf- the slight of hand,

the real ambivalence or feigning of disinterest, which is quite an

extraordinary thing for a painter to do (pre-deadpan, post-pop anyway), painter

and viewer taking on more of an emotionally or dramatically situated response-

and not a simplistic melodrama, but the drama of understatement, restraint, of keeping things withheld.

That Sickert often plays the impartial

observer, is a kind of character or narrator protesting neutrality, is often

part of the pictures’ content. The ‘looker’ ends up being as fugitive and

enigmatic as the looked at (Kenneth Clarke comments in the catalogue of the

Nicholson/Yeats show that Nicholson ‘like all good essayists [looks] at his

subjects, animate and inanimate, with a kind of humorous sympathy. His comments

are so tactful and urbane that some of his pictures may at first seem to be

plain statements of fact; and probably he would claim no more for them. But we

are not long deceived by this half-ironical reticence.’ Nicholson is a kind of

Hemmingway to Sickert’s Woolf, Yeats’ Joyce or Beckett, Daumier’s Hugo or

Cervantes- these painters as complex and developed in how they narratively

position themselves, their subjects and their ‘readers’. Indeed the Manet also seems to weigh-up pictorial vs. literary absorption.)

This kind of understatement and ambiguity

is a dominant characteristic of the Camden nudes. We can never really be sure

of what is going on in them (nor our own position as viewers). A liberated

affair, a dead-end romance? Are we supposed to be aroused or deadened by habit

and familiarity? Is the implied viewer necessarily male (in the pictures of

lone women)? Criminal? Do they show husbands or lovers dressing for work, or

clients about to leave? Or killers? Do they merely show the act of modelling

and painting, the relationship of clothed painter and naked model? Are the

relationships fundamentally happy or unhappy, professional or intimate, do they

depict cosiness or squalor, life or death, morning or afternoon? Across the

series, the painting becomes the room- an embryonic chamber, sealed off, which

we peer into or out of. As much as they might refer to sensational news stories

and public morals, they are also about shutting ourselves away, privacy,

hermeticism, the warmth and life of beds and bodies, dressing and undressing,

wasting the day away. The rupture of being naked with someone who isn’t. And

all this within the basic set-up of painter and model- there is as much a

notion of the room being a kind of learning, thinking, experimenting chamber, a

rehearsal room where these notions are played out. They feel much more

knowingly staged than Degas’ studied voyeurism, we are frequently much more

aware of the women as models (in a

way they are embodied explorations of late-Victorian sexuality but also

explorations of the very tradition of the nude- far more genuinely explorative

and humane than the worthiness of Freud’s, say, on the nose, stale

existentialism).

Sickert was highly conscious of their

mutability- retitling the innocuous social realism of paintings like What Shall We Do For the Rent? to explicitly

reference the contemporaneous Camden Town

Murder. Perhaps this was a calculated attempt to capitalize on the notoriety

of the local incident, just down the road from his studio, yet it also suggests

Sickert was highly conscious of image fluidity, viewer projection, framing.

Indeed, according to one of his models, Sickert would meditatively ‘act’ the

part of the murderer, propping the studio accordingly, like an analytic

Sherlock Holmes brooding over his pictorial ‘problem’, and the sheer charged

ambiguity and mystery to the pictures attest to his developed sense of the

phycology of images.

And again, looking away is not the only

kind of looking Sickert’s involved with- its all the more singular when he

chooses to look directly at a subject. The

Lady in a Gondola (54.) is a particularly striking early example (and an early

experiment with photographic sources, the sitter never having sat for Sickert

nor visited Venice), strangely cropped off-centre, the woman leaning back

slightly awkwardly (we feel the very slight pull and tug of the boat on her

unsupported head), though she might as well be falling back into reverie

against a wallpaper backdrop. It’s an early example of Sickert slipping into

his ‘adoration’ mode- the portrait and background fusing into an invented

idealization, and suggesting that memory is often just such a confection.

Indeed, his adoring portraits of actresses-

frequently in profile- are absolutely

aware of how they themselves brazenly play their part, knowingly performing the

role of signed mementos, while classicizing, idealizing, and pulling it off.

Gwen

Ffrangcon-Davies as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (55.)

is a kind of ‘signed portrait’ in the sense of something inscribed, dedicated

and gifted to a devoted fan or admirer as much as the painting is Sickert’s

‘gift’ or tribute to his subject, her name and Sickert’s scrawled almost

illegibly across it (signature and likeness as stand-ins, substitutes in lieu

of the absent party). It could be signed from her to him or him to her. And yet

it also acknowledges its own illusions and delusions; she is playing a role,

perhaps imbued with another personality, perhaps only ‘known’ to the

painter/viewer through a performed character, admired from a distance, speaking

also of how we create the objects of our affection, write them into a narrative.

She is a ‘substitute’ Browning just as the painting is a substitute Ffrangson-Davies,

and the image explores wider notions of memory, substitution, performance and

impersonation.

To an extent pretending to be a study or sketch, an underpainting/understudy, it is both hauntingly, tenderly, beautifully painted yet clearly somehow photographic, sepia toned, dirty, smudged, rough even. Its surface is so thin and so exposed that it is less like a painting and more like a kind of precious imprint (perhaps again musing on the nature of photographs, or the mythic origins of painting, the silhouette of the departing beloved traced on the wall, etc.).

It somehow simultaneously takes on the condition of a stolen glance and a lastingly, lovingly, carefully rendered likeness. We come back to Sickert’s attitude to memory and copying, translation and transcription (indeed he spoke about the process of making paintings after photographs as being like an actor interpreting a role). The depiction itself doesn’t fall into cliché, at least in terms of the denotation of shapes; the eyes are either downcast or blank, forehead and chin are exaggerated, the hair and clothes fall awkwardly, unintelligibly, perhaps into one another (cover up the face and the rest of the picture refuses to cohere as ‘hair’); the features are sharp, flat, yet softly touched; we cannot strictly place her shoulders. Most movingly she seems to be speaking, or just about to- but remains, obviously, silent. The crumpled form near her mouth seems stunted in its expression, like a withered hand, or a rose, or maybe just a gathering of hair and clothes after all- it is one of Sickert’s indefinable, camera-based mystery forms, which refuse to allow themselves any remote graspability, but which generate deeply buried associations.

To an extent pretending to be a study or sketch, an underpainting/understudy, it is both hauntingly, tenderly, beautifully painted yet clearly somehow photographic, sepia toned, dirty, smudged, rough even. Its surface is so thin and so exposed that it is less like a painting and more like a kind of precious imprint (perhaps again musing on the nature of photographs, or the mythic origins of painting, the silhouette of the departing beloved traced on the wall, etc.).

It somehow simultaneously takes on the condition of a stolen glance and a lastingly, lovingly, carefully rendered likeness. We come back to Sickert’s attitude to memory and copying, translation and transcription (indeed he spoke about the process of making paintings after photographs as being like an actor interpreting a role). The depiction itself doesn’t fall into cliché, at least in terms of the denotation of shapes; the eyes are either downcast or blank, forehead and chin are exaggerated, the hair and clothes fall awkwardly, unintelligibly, perhaps into one another (cover up the face and the rest of the picture refuses to cohere as ‘hair’); the features are sharp, flat, yet softly touched; we cannot strictly place her shoulders. Most movingly she seems to be speaking, or just about to- but remains, obviously, silent. The crumpled form near her mouth seems stunted in its expression, like a withered hand, or a rose, or maybe just a gathering of hair and clothes after all- it is one of Sickert’s indefinable, camera-based mystery forms, which refuse to allow themselves any remote graspability, but which generate deeply buried associations.

Ultimately she slips away, despite her

indelible presence. The brief encounter of an autographed picture, framed.

The ‘actress’ pictures show that just as

Sickert’s attitude to composition isn’t standardized, neither is his attitude

to photographs. Variation on Peggy (56.) is

a similar profile, with a similar rudimentary background to the Lady in the Gondola- based on a press

clipping, the image is transformed, synthesizing his own past (the green and

pink of his St Mark’s) and making the image emphatically ‘picture-like’, willing

the snapshot into something more robustly emblematic, to go on lasting. Gwen

Ffrangcon-Davies is also transformed from her portrayal of Browning in Gwen Again (57.) - based on a stilted publicity

image, it’s a glowingly exaggerated, glamourous melodrama in velvet and silk

(tellingly now owned by Roxy Music’s Bryan Ferry), Sickert playing even more

fast and loose with the inclusion of script, signature, photographer’s credit

etc. These would be yet more apparent in the bottom portion of the related

picture Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France (58.) mixing serif type with something close

to handwriting and then his own jagged signature in dark pink, juxtaposing the

poster-like title and credits with a huge abstracted expanse wherein the dress

becomes almost like an architectural encasement, a pile of cracked meringue and

cream in a green-y pink almost reminiscent of Guston. He also anticipates pop’s

fascination with image reproduction and degradation, the thick weave of the

canvas across which marks are stained and scumbled making it seem like a giant,

grainy blow-up pasted over peeling layers of old posters.

|

| 57. |

|

| 58. |

Indeed it’s important to note that the

photo-based pictures come from a wide range of sources- newspaper clippings,

film or theatre lobby cards and press images (which themselves are often re-stagings

of ‘real’ performances), commissioned portraits, impromptu studio snaps, and

even rehearsed and choreographed images under Sickert’s own direction.

|

| 59. |

We see something of the young actor Sickert

re-emerge as a kind of Lear or Falstaff in the grandly titled ‘biblical’

self-portraits (Lazarus Breaking His Fast

(59.), The Servant of Abraham (60.)) in

which he purposefully, gleefully cultivates a crazy old man kind of image,

simultaneously Old Master and coot, a figure of humour and pathos. Several

areas of these canvases accept the unintelligible patches of their source

photographs, the camera overloaded by strong light, dissolving the forms or

removing from them their clarity and distinctness. With the yellowed palette

they can’t help but recall a kind of cataract vision, or a loss of one’s grasp

on the external world, Abraham particularly

filling the frame with the artist’s head, the one staring eye cocked the other

seemingly glazed over, vision turning inward, mystic even, in spite of the

apparent frontality and documentary objectivity of the photograph.

|

| 62 |

Similarly, in The Tichborne Claimant (61.), based on a press portrait of a famous

criminal from his youth (with whom he had something of an obsession), Sickert

deals with notions of imposterism, acting and authenticity. The blank, almost

anonymous, ‘official’ looking portrait with its incongruous landscape and

de-saturated palette, becomes almost like that of a bank note or forgery (it

also anticipates the contemporary work of Michael Fullerton- particularly his

portrait of Kim Dotcom (62.)- which explores ‘submerged’ narratives or systems

of information, power, corruption etc. via seemingly innocuous portraiture,

often based on photographs). The Claimant would go on to tell his story as a

theatrical turn upon his release from prison in the 1890’s, and in a way

Sickert conflates criminality and theatricality throughout his oeuvre, painting

as a form of subversive perjury, theft, character assassination (the Claimant

also falls as a halfway house between the Victorian villains of the Echoes and

the late photographic works, while already suggesting the ambivalent nature of

photography’s ‘documentary’ status).

|

| 63. |

|

| 64. |

The ‘big-heads’ of Abraham and the Claimant

can be grouped along with the heads of Ffrancon-Davies and of the singer

Conchita Supervia (63.), as well as the famously provisional portrait of Sir Hugh

Walpole (64.). The heads (they are often more like ‘heads’ than ‘portraits’)

seem to explore notions of presentness, knowability- sometimes adoring,

sometimes inscrutable. Walpole seems to exude presence despite being so eroded,

a sense of admiration or affection, certainly warmth- Sickert almost seems to

be depicting the energy that temporality animates the human aspect or essence,

the image somewhat like an old Victorian trick-photograph of a medium taken

over by a spirit, auras and ectoplasm etc. (suggesting obvious parallels with

the notion of portraiture itself. The tilt of the head and the hazy features

also point back towards the Lady in the Gondola, with its negotiations of

presence and dispersal, closeness and distance).

As much as the portraits are about ‘presence’

they are also frequently about self-presentation. Sickert seems to have been

particularly alive to the effect of photography on people’s behaviour and their

behaviour in images. Edward VIII skulking out of a carriage (65.), George V and

his Racing manager (66.), Lord Farringdon (67 .), are all total revisions of Royal

or society portraiture in composition and in body language- the royal pictures

candid and revealing, Farringdon ‘acting’ the part, smiling to the assembled

guests or photographers. These pictures reveal the subject as somehow empty and

insubstantial, or how they can seem to be, caught off-guard or trying too hard;

the king staring blankly ahead while his racing manager (who might as well be a

royal advisor on any matter) sits whispering on his shoulder, the line of the

manager’s mouth continued by the King’s moustache, registering as a weird kind

of scarred grin, a Chelsea smile (it seems a deliberate exaggeration from the

photo to make them effectively ‘share’ the one mouth as much as they share a

hat- the manager almost a smudged, shabby Mephistophelean reflection in a

mirror); Edward VIII spindle legged and boyish, holding his oversized hat in

front for a shield, like an orator expecting eggs; Farringdon propped up by an

impromptu, mohair peg-leg.

|

| 66. |

|

| 67. |

Indeed pictures like Farringdon, Lord Beaverbrook (72.) or The Viscount

Castlerosse (68.), are as much about a certain kind of trouser leg hitting a

certain kind of leather shoe on a certain kind of tiled step or a certain kind

of carpet, as they are about their ‘sitters’. Often the subjects are defined

less by their hazy facial features than by dress and stance, posture. As much

as the pictures are to do with photography’s flattening of tone and contrast

into positive and negative blocks and wedges, they are about how people behave,

how they stand, what they wear, the photographed’s awareness or not of the

photographer, and, in turn, how certain sartorial decisions, certain cuts of

clothing seem almost driven by how high-contrast photography and low-quality

reproduction render tailoring (Edward VIII introduced the ‘midnight blue’

tuxedo, which photographed better as ‘black’ in the newspapers, for example-

and in Farringdon Sickert latches onto the swoop from wide lapel to trouser

pleat, one shiny arc). The clothes frequently seem more solid than the wearers,

inhabited by them, or are at the very least partially about the nature of worn

things, garments, the way they follow or drape from the body, their relative

weight and stiffness or lightness and softness (the viewer is to an extent

invited to try-on the role of the blanked-in sitter- again, a novelistic

inhabitation of character yet one distinct and specific to painting).

|

| 68. |

His portraits of the Martin family (69., 70., 71.) would go even further in their

appropriation of photography- blatantly portraying how photographs portray

rather than strictly portraying the ‘sitters’. In this he anticipates everyone

from Tuymans (particularly the pearly, de-saturated palette) to Richter, etc.,

but his formal fascination with the effects of dress, how it registers tactually

with a viewer, how it can be the dominant note (or one of the dominant notes) of

a picture without being vacuous, is surely more like Alex Katz- in the way that

a Katz can be about wearing a certain

hat, or shirt, or shades on a certain kind of day, the relative looseness or

tightness at different parts of the body within different stances, and the

formal/tactile tensions and releases therein (and so about wearing them in a way that no other art form can quite be).

|

| 70. |

|

| 71. |

Similarly, like Katz, it’s not so much that

he merely copies or renders or approximates the conditions of photography, but

rather that he has also somehow nudged himself back into the position of the

photographer, re-inhabiting the original ‘looker’, transferring some sense

either of closeness to or remoteness from his subject, almost as if we are back

in the moment, back in the instantaneous psychology of the snapper, in the

moment of the decision to release the shutter, in the recognition of the emergent picture. And in this we come back to a

Daumier-esque consciousness and internalization of the ‘picturer’, the very

notion of a picturer, yet one which negotiates painted construction and

reconstruction with that of the newer, instantaneous media. Katz, rarely

working directly from photographs, cuts out the middle-man, is himself the

‘photographer’, negotiates and synthesizes a photo-type with a painting-type of

picturing, while the extent of Sickert’s tampering with the source image waxes

and wanes across the work and towards varying purposes.

|

| 72. |

For example, he can re-feign a kind of

journalistic, factual poetry- in Miss

Earhart’s Arrival (73.) – pinpointing the perfect moment that sums up, not

the scene, quite, but something over and above the incident ostensibly

portrayed, while radically cropping and obscuring the image; while in Jack and Jill (74.) he simultaneously

takes the place of a cinema goer, lending the image a silvery, projected

quality, while also rendering the image more physically present than the flat

publicity still it is based on.

Miss

Earhart’s Arrival was rightly celebrated in its

day- surprisingly so, as Sickert’s late photo-based pictures were more often

than not met with derision, either for their muddy provisionality, for the fact

that he seemed to represent his subjects as being somehow shabbier or more

incidental than they should be, or purely and simply because he was ‘cheating’,

that these photo-copies just weren’t cricket.

|

| 73. |

The famous pilot’s arrival is pretty much

blocked by the crowd, by the rain. There’s something of a contrast between the

opening up of the world through air travel and the huddled constriction of the

crowd- the very idea of elevation vs. the soggy weight of the gathering on the

landing ground. Typically Sickert, his attention rests not on the flight or the

touch-down, or even the arrival really, but on Earhart’s departure: after the

build-up and the queueing, the famous person will duck under an umbrella and

into a car, will disappear into the crowd before the crowd itself disperses.

Everyone seems to be looking the wrong way, or looking at nothing, or at

something outside the frame, or perhaps they have missed it- waiting for

something to happen and realizing that it’s been and gone. Time to be moving

on. And perhaps even the clouds will pass and clear, this particular

constellation of place, people and elements that is the picture lost forever.

It also seems to wonder about modernity in

painting, and whether the contemporary moment can be looked at directly or must

be mediated, screened and framed (the wing of the plane another umbrella or

turn of the century French parasol), so as not to create a total rupture from

the history of the form. Katz does a similar thing- dress and hairstyles, forms

of self-presentation, are from a present moment, yet we rarely see cars, phones,

TVs, laptops etc., despite their absolute ubiquity. Somehow Sickert and Katz

suggest that the speed or conditions of these things seem better expressed

through formal design, overall effect, rather than explicit depiction. We

instantly ‘get’ that the Sickert (with its grainy dynamism, the slashing

raindrops, the cropping) is from an era of adventurous air travel, Pathé newsreels

and emergent photojournalism, we get that a shiny Katz is from a moment of polaroids,

Trim phones and tube TVs, or cell phones and sat-nav, without these things

puncturing the ‘poetics’ of painting continuity, without short-circuiting the

past/present oscillations within the image. The picture retains its present yet

ambiguous relationship with time.

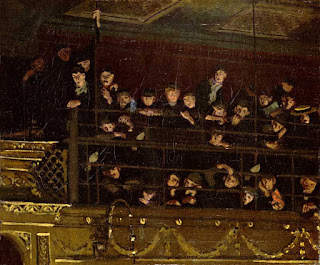

Similarly Jack and Jill might be Sickert engaging with contemporary cinema,

yet it goes all the way back to the up-lit performers/audiences of the music

hall, the Lion Comique, Minnie Cunningham (76.), The Gallery of the Old Bedford (75.) etc.

|

| 74. |

|

| 75. |

|

| 76. |

Jack

and Jill, the English Echoes, the newspaper images,

are all re-capitulations of the Camden Town pictures and the music halls of the

previous century; their melodrama, grande

gringol sensationalism, by turns gothic and parochial; the hypocrisies and

vagaries of taste, the narrative, visual and vernacular languages of British

culture in the 19th-20th centuries. Sickert is very

sensitive to the emergence of types of image, and it’s a natural step within

his oeuvre to pass comment on film noir upon its arrival in Britain- with its double-crossings,

femme fatales and cruel turns of fate, Sickert surely would have seen this most

apparently ‘modern’ and urban of genres as not so far removed from his

Victorian rouges and morality plays, Jacobean drama or the Sunday papers.

Cinema had been tried and tested in

painting before- even by Sickert as early as 1906 (The Gallery at the Old Mogul (77.), often said to be the first ever depiction of the new medium, it also brings to mind Daumier's crowded carriages full of travellers and immigrants, the flashing windows replaced by the movie image, carrying with it ideas of transportation/escape) and famously by Hopper

(78.) – but without such blatant screen-grabbing and wilful two-dimensionality,

the image fully cropped to the implied ‘screen’ rather than the conventional compositional

conceit of showing audience, auditorium, and the image-within-an-image projection.

Weirdly it even looks more convincingly ‘filmic’ than the promotional still it

was drawn from (79.): Sickert doesn’t just paint the image but internalizes a

sense of cinema’s illumination, whether of the projection or literally under

studio lighting, or perhaps even the light reflected on the audience, the

characters here could just as easily be watching the events onscreen, touched

and transformed by its rays (suggesting further themes of presence and

sublimation, identification, the new ways people’s interior lives and

behaviours are coached and dramatized by popular forms- the men leaving the

theatre perhaps carrying themselves with a note of Edward G. Robinson, an extra

tough twinkle, the women perhaps imbued with a hint of Joan Blondell, feeling

extra tough and tragic). The distinctive red, blue, green, brown of colourized

lobby cards can also be detected here even without reference to the probable

source poster, which is again a recapitulation of the Echoes’ ‘hand-coloured’

illustration effects, while the title Jack

and Jill refers neither to the actors nor to their characters but renders

them both types- simultaneously stereotypical American cop/gangster names,

blunt and monosyllabic, but also echoing old English nursery rhyme (a typical

Sickert antithesis).

|

| 79. |

Such activities- painting the famous and

infamous, copying telling newspaper images, using stills from films,

appropriating ‘folk art’ and popular or vernacular imagery, heightening

reality, internalizing the conventions of cinematography or photojournalism-

are all strategies which are pretty much still part of the program today (bits

of the famous people- Doig, Dumas, Tuymans etc.- can all be found in Sickert).

Indeed, entire practices and reputations are sometimes based around just one of

these strategies employed by Sickert at the end of his long career, some 80 odd

years ago. And yet frequently these strategies are still either presented as

something novel enough to hang a reputation on, or are more dispiritingly

worked through essentially as strategies

pure and simple, with little invention or formal/thematic depth. Frequently

they are processes and readymade, provocative or discursive subjects thrown up

in place of any real substance or any true engagement; any of the thematic

reflection upon or interplay between these processes and subjects which seems

so alive in Sickert.

Criticism often has to wrestle with the

fact that Sickert, certainly in his very last years, relied on the help of

assistants- at first merely to start off the underpainting of his so-called ‘camaieu’

technique (wherein a contrasting blue or pink, say, would make a ‘cameo’ appearance

through the thin patches of surface colour), while the paintings from the last

year were all but entirely painted by his wife, the painter Therese Lessore, under

his direction; the two of them, captain and first mate, swamped under an ocean

of newspaper cuttings, magazines and phtotgraphs on sunny afternoons in the

room he called his ‘cabin’. But the ‘images’ were his, the colour effects,

compositions and so on, while Lessore (who’s touch was already sympathetic to

the late Sickert style) did far more than a convincing impersonation,

internalizing and pulling off the demands of the role so that the pictures

might as well have been by the old man himself. They were ‘Sickert’ paintings –

for all those interested in untangling authorship might want to debate- signed

off, approved within the Sickert’s picture lab, and frequently quite unlike

anything anyone else was doing at the time.

.

…it

does to tack together torn bits of stuff, stuff with raw edges. After all, one

cannot find fault if…one begins letters “Dear Sir”, ends them “yours

faithfully”; one cannot despise these phrases laid like Roman roads across the

tumult of our lives, since they compel us to walk in step like civilized people

with the slow and measured tread of policemen though one may be humming any

nonsense under one’s breath at the same time- “Hark, hark, the dogs do bark”,

“Come away, come away, death”, “Let me not to the marriage of true minds”, and

so on.

-Virginia

Woolf, The Waves

I began by stating that the big

continuities across Sickert’s oeuvre are the popular image/form and the

condition of the passing world. And while this, surely, is an

oversimplification, I would certainly argue that it is somewhere within the space

of this endless re-combination (of the vernacular, the clichéd, the obsolete or

the fading-away, of the continuities/ruptures of past and present) that Sickert

finds his most powerful subjects and images.

In fact, he already reached something of an

elegiac summation of all this at the (pretty much) mid-point of his career:

1915’s Brighton Pierrots (80.).

|

| 80. |

Brighton

Pierrots is in many ways a potted summary of

Sickert’s career up to that point, recalling the pastels of Degas, the street

performers of Daumier as well as Sickert’s own fascination with the music hall-

while pointing the way to the Echoes, to Yeats, to the colour and handling of

the late work.

Reproduction fails to quite get across how

the colours in this picture throb and smoulder, partly through the effects of

Sickert’s late touch, the patches humming and vibrating against one another

almost as in a pastel. The image is ostensibly crepuscular, the light fading-

yet it’s a powerful, deep dullness.

The performers, who play for mostly empty

wartime deckchairs, appear like apparitions haunting the band-stand, repeating

their act perhaps for the last performance of the day. They could almost be

materializing with the setting of the sun, or spectres cast away by the light

of sunrise (see the fading figure on the far left). The top-mid stage-light

registers at first more like a bird flying away- whether a dove from a

magician’s sleeve or just a common or garden gull. It’s a typical Sickert image

of transition, dispersal, a change in state or register, the emergence of

something on the cusp of poignancy, something about to end; the performers with

the infinite sea behind them, the candy-coloured cardboard city in front, caught treading the

boards of the moment. On the one hand it’s like the half-remembered

two-dimensional figures of the Echoes becoming real in the cold evening breeze;

on the other, the players becoming lost in time, loosing their physical

presence, becoming an image; in fact, they are caught between the two states, physicality

and image, by the pitch and nature of the painting, its handling, the

composition, the marks, the tones and hues, suspended in its own specific

balance of naturalism and theatricality, solidity and fragmentation.

|

| 81. |

In some ways a proto-Echoes picture (the

re-make in the Ashmolean (81.) isn’t at quite the same emotive pitch, it’s more

like the slightly more frivolous or illustrational of the Echoes) the Pierrots is in many ways riddled with

clichés; yet it finds within them something real and precious; precious because all we really have, in the end; bits of ideas we string together in order that we might make some sense of life, snatches of tunes we whistle in the dark. Sickert marshals the clichés- the

show must go on (till it ends), greasepaint and footlights, empty stalls, tears of a clown Anthony Newly-isms, the off-season seaside, the

sunset etc.- into a distinct new proposition: one of natural vs. synthetic light, fashion and costume, redundancy and supersession, tradition vs. the

contemporary moment, but above all a moving juxtaposition of sheer futility (the equal of contemporaneous

war poetry, Owen’s ‘fatuous sunbeams’), with absurdity, the sheer unlikeliness of

the world, all its wasted energies, all its 'useless beauty'- and yet also a kind of resigned, stoic acceptance of things as

they’ve been, are, and shall be. An acceptance, even, as much bemused as bitter, as much bitter as hopeful, that they should have been, are, and will be at

all.

.

But

we have gossiped long enough, they said; it is time to make an end. The silent

land lies before us.

-

-Virginia Woolf, Walter Sickert: a Conversation

.