And in the pictures: does not the image remain

of your eyebrow's dark streak

scrawled rapidly across the wall of your spin?

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus XVIII, translated by Martyn Crucefix

And in the pictures: can't we still see the drawing

which your eyebrow's dark evanescent stroke

quickly inscribed on the surface of its own turning?

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus XVIII, translated by Stephen Mitchell

H/P

While Derain speaks in a kind of ‘Old High-Painting’,

he wasn’t exclusive in his sources. However ‘classical’ he gets, however

retrograde, there is always something unmistakably inter-war, 30’s, 40’s about

his work (rather like contemporaneous poets Pound, Eliot, even Cummings, Williams), particularly in the portraits.

Something like Han van Meegeren’s famous

Vermeer fakes from the period, they can occasionally be jarringly ‘Hollywood’ in their

lighting or cosmetics (he was an avid cinema fan), the portraits of a contemporary, popular

‘type’ of look despite their classicism. Across the paintings he’s alive to the

particulars of make-up, the sweep of hairstyles, the application and alteration

of appearances, lipstick, eyeliner, kohled brows, which in turn inform the

depiction of fruit stalks, highlights, handles, tree trunks. All carry his

calligraphic, just-so swipe. (Or he'll purposefully fudge

things, the 'forehead' in fig.18. working as a cancellation of the

brushmark's inherent predisposition towards natural 'hairline' shapes

and behaviours). Throughout the notebooks are various hieroglyphs,

passages of italicized script, Hebrew characters, units of gesture

and communication which are mirrored in the handwriting of his

paintings, the marks wriggling free of their cursive bonds, while there

is also a sense of 'over-painting' in

many of his later works, a sense that the picture is almost pan-sticked

and

eye-linered, the image scrunched, puffed, crimpled, chiffoned.

There's an undeniable parallel drawn between the the application of additional contouring and definition, layering and blending in cosmetics as in painting. The portraits run with notions of illusionism and styling, augmenting and 'improving' on reality. Derain employs slick, skilled marks and accents which paradoxically pop the illusion; the marks themselves give physicality, yet emphasize the pictures' surface, their flatness, bring their physicality and their illusionism up short. He interrogates beauty, just as he celebrates and sabotages it. Throughout his work, in whatever genre, it's rare for him not to leave at least some small sign of human presence or activity- 'beauty' residing in the process of human apprehension and adaptation rather than an inherent property.

There's an undeniable parallel drawn between the the application of additional contouring and definition, layering and blending in cosmetics as in painting. The portraits run with notions of illusionism and styling, augmenting and 'improving' on reality. Derain employs slick, skilled marks and accents which paradoxically pop the illusion; the marks themselves give physicality, yet emphasize the pictures' surface, their flatness, bring their physicality and their illusionism up short. He interrogates beauty, just as he celebrates and sabotages it. Throughout his work, in whatever genre, it's rare for him not to leave at least some small sign of human presence or activity- 'beauty' residing in the process of human apprehension and adaptation rather than an inherent property.

|

| 18. |

Again

and again Derain finds relationships between the paintings as

physical things and their thematic content. In the case of the

portraits, subject

and handling measure the ‘façade’, the surface, against interiority,

expressivity, depth. The

faces, or ‘heads’ (for they are sometimes more one than the other),

themselves provide

a field for endless investigation. They can be psychologically

penetrating,

imposing, disarming, or they can be doll-like, impassive, statuesque,

mask-like.

(The

number of them worth time and attention belies the sheer volume

produced. Compare the way the head fills the frame from one to the

other, their tonal variety, their handling etc.).

They seem equally (and remarkably, for

the time) knowing about their own artifices, their own limitations even, the

women depicted frequently falling into certain categories or feminine ‘types’,

playing certain roles which are ostensibly male-defined. Indeed, the 'heads' are potentially

problematic in that they could be seen to objectify women in the same way that

Derain’s paintings ‘objectify’ trees, villages, apples, etc., reducing them merely to examples, specimens.

What can become problematic with painting is

that it cannot help but ‘objectify’, in both senses of the word. It reduces the things of the

world to a series of remote surfaces, presented for aesthetic consideration,

reduces its subjects to their silent appearances. But it also ‘objectifies’ in

the sense of expressing some abstract feeling or notion in concrete form,

literally rendering thought and expression as an ‘object’, exteriorizing and

attempting to make more or less visible and graspable some elusive

condition of being. It’s a queasy thing, particularly in these head paintings, but I believe,

and I would argue, that Derain is exploring precisely this problem: that the portraits investigate this biforcated objectification under which painting operates, that they present to the

viewer both the shallow sense of a generic ‘woman’s face’, while expressing

in plastic terms the weird and complex bundle of cultural-personal,

conscious-subconscious associations and conditions which such ‘faces’ might provoke

or mask.

I wouldn’t want to make this an outright

apologism for the pictures’ sexism, to whatever degree, but can only argue that

Derain’s approach toward type and example here is, for better or worse, entirely

consistent with his landscapes, still lifes, et al. That the women’s submission

to, engagement with, personal adaptation, subversion or rejection of these

given ‘genres’ of face-making and self presentation, these given looks and

roles, present a radical re-articulation of his lifelong ‘theme and variation’ fixation.

Derain measures the women’s ‘type’ (as well as type of pose or attitude) against their individuality. As with the landscape and still lifes, they may be a type of something, but they are also strikingly singular, and, as with the paintings in other genres, there is a demand that we spend time to get to know them, to look further and further into their idiosyncrasies. They play with perennial portraiture concerns- estrangement, recognition, the encounter, countenance and character, closeness to or remoteness from the viewer, direct and indirect gazes- which extend as always to the paintings themselves, in their compromised state as pretty surfaces with hidden depths.

While these complexities stand out from the many generalized 'portraits' of the time, regrettably the queasiness of painting’s 'objectification' can't help but become amplified in paintings of women (overwhelmingly excluded from technical, professional or social initiation into the field) by men, no matter how well intentioned. But I think we owe Derain the benefit of the doubt. He pursued these faces with the same care and invention that he did all his work- in all its complex shallowness and depth.

In some ways the faces are just too purely and simply strange to be passed off as superficial, mild-erotica (nevermind easily digestible 'eye-candy') as are the wider series of nudes and figures .

C

Derain measures the women’s ‘type’ (as well as type of pose or attitude) against their individuality. As with the landscape and still lifes, they may be a type of something, but they are also strikingly singular, and, as with the paintings in other genres, there is a demand that we spend time to get to know them, to look further and further into their idiosyncrasies. They play with perennial portraiture concerns- estrangement, recognition, the encounter, countenance and character, closeness to or remoteness from the viewer, direct and indirect gazes- which extend as always to the paintings themselves, in their compromised state as pretty surfaces with hidden depths.

While these complexities stand out from the many generalized 'portraits' of the time, regrettably the queasiness of painting’s 'objectification' can't help but become amplified in paintings of women (overwhelmingly excluded from technical, professional or social initiation into the field) by men, no matter how well intentioned. But I think we owe Derain the benefit of the doubt. He pursued these faces with the same care and invention that he did all his work- in all its complex shallowness and depth.

In some ways the faces are just too purely and simply strange to be passed off as superficial, mild-erotica (nevermind easily digestible 'eye-candy') as are the wider series of nudes and figures .

|

| 19. |

C

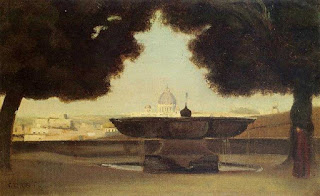

It’s probably worth mentioning at this

point that perhaps the single biggest influence on Derain (and Derain was a

wide and voracious sea-sponge after all) was Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.

Corot, the great landscape painter,

the bridge between the classicism of Claude and the empiricism of the impressionists,

was a natural Derain touchstone. It’s his by turns diffused, silvery, flecked and silky,

by turns buttery and saturated, olive-oily light that we see again and again

throughout Derain’s landscapes (19.);

Corot’s oil-sketch strokes and swipes, allowed to increasingly infiltrate

‘finished’ canvases that lead to Derain’s surface marks; his predilection for

off-set graphic blocks and shards of light or shadow that lead to Derain’s

scattered jigsaw flecks and characters (20., 21.). The debt owed to

the older artist’s coastal/harbour scenes is undeniable (22., 23.).

|

| 20. |

|

| 21. |

Indeed Derain would return to the places

where the breakthroughs of Corot, Rousseu, Courbet and the rest were made and modern

French painting born. Part archaeologist, part pilgrim, he would haunt the

landscapes of Fontainebleau, Barbizon, Granville- as the film documentarian Mark

Cousins said of himself and movies, Derain wanted to be ‘close to the contours’

of painting.

|

|

| 22. |

|

| 23. |

However there was a hidden side to Corot’s corpus that remained largely unknown until after his death: just as influential on Derain were the artist’s figure paintings, works carried out as a kind of private project between the celebrated landscapes (Corot described them as a necessary break, a holiday from his main activities which he reportedly looked forward to).

With variation upon variation of

dreamy figures in repose, these pictures represent a private research which

must have struck a chord with Derain. He would surely have been exposed

to Lady in Blue (24.) the first of Corot’s

figures to see the light of day, at the Exposition of 1900. There’s definitely

a Derain-ish inconsistency between the picture’s top and bottom half, firmer

modelling dissolving into feathery strokes.

In fact, the overwhelming majority of Corot’s figure paintings contain some moment of pictorial disruption, carry some deformity; an inconsistency of draughtsmanship between, say, one hand and the other, the head and the shoulders, malformed limbs hanging from dresses. It’s easy to put this down to simple clumsiness (or carelessness in that they were never intended for exhibition) but its these elements which allow them a startling modernity. They prefigure the oddness of Derain’s semi-classicized faces, all shadowed, sculpted eyes, or the elisions of his anatomy, the biomorphic distortions of Picasso, etc. The inconsistency of Lady in Blue later becomes the jitteriness of The Beautiful Model (1923 (25.)), with it’s oddly straightened, bookend back, which in turn reacts with the sudden caligraphic swipe against the belly button, creating an erotic, jerky frisson.

|

| A.D. |

In fact, the overwhelming majority of Corot’s figure paintings contain some moment of pictorial disruption, carry some deformity; an inconsistency of draughtsmanship between, say, one hand and the other, the head and the shoulders, malformed limbs hanging from dresses. It’s easy to put this down to simple clumsiness (or carelessness in that they were never intended for exhibition) but its these elements which allow them a startling modernity. They prefigure the oddness of Derain’s semi-classicized faces, all shadowed, sculpted eyes, or the elisions of his anatomy, the biomorphic distortions of Picasso, etc. The inconsistency of Lady in Blue later becomes the jitteriness of The Beautiful Model (1923 (25.)), with it’s oddly straightened, bookend back, which in turn reacts with the sudden caligraphic swipe against the belly button, creating an erotic, jerky frisson.

|

| 24. |

|

| 25. |

|

| 26. |

The

women (they are mostly women, yet

there are occasional male figures, humorously reclining (26.)) look to

be made-up, or

at least largely composite in character. There’s a disconcerting feeling

of

unreality to them, as if we’ve suddenly come across the people that

inhabit Corot's

peculiar painting-land, the distant figures from his dappled landscapes

seen up

close, and a listlessness to many of them, as if their minds have been

left half-formed. Many resemble novelty photographs, the figures posed

against fake

backdrops with a ledge or a rock to lean on- fantasy images (even Derain's landscapes or still lifes are allways somehow 'made-up', fantasy landscapes, fantasy still lifes).

|

| A.D. |

In some ways both

Corot and Derain recall Fragonard’s figures

de fantaisie of the previous century (27., 28.)- pictures executed almost for the sake of it, excuses for paintings. Knowingly over-the-top, knowingly 'painted',

Derain’s pictures can similarly morph into outré, neo-rococo territory, can

play painterly dress-up and parlour games.

|

| 27. |

|

| 28. |

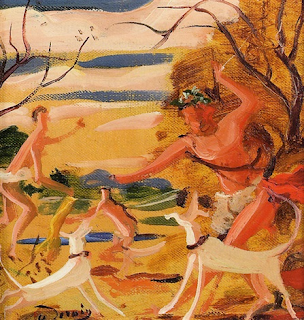

Scenes

of hunts, across country parks

or formal gardens can in turn metamorphose into pseudo-quattrocento,

pseudo-mythological

Bacchanals, creepy and haunting in the way they re-imagine a certain

kind of over-cooked painting (29., 30., 35.). Their painterly

reinvention recalls that of Bob

Thompson in the 1960s (31.- 34.) crackling

with energy, super-conscious, savvy and child-like at the same time,

exploring the implications of 'plurality/unity' raised by the

patchwork-quilt composition of Renaissance or Baroque painting.

|

| 29. |

These are rarely close to the kinds of arcadia painted by his contemporaries (Matisse’s Luxe, Calm, et Volupté, La Danse etc.), carrying instead a feeling of immanent menace. Some have a child-like picture-book or nursery rhyme quality, (One man went to mow, went to mow a meadow (36.), A sailor went to sea sea sea to see what he could see see see (40.))- but even The Bagpiper at Camiers (41.) is more a kind of mesmerizing Pied Piper in his jingle-jangle morning, his playing twisting the road ahead like a charmed snake. These pictures can vary between patchy, dry Cezannisme, Jack Yeats-ish impasto, even a kind of rudimentary, ‘armature’ quality that recalls Lowry (37.-39.) (indeed Lowry’s and Derain’s series of ‘Heads’ could be seen as the results of two differing temperament’s approaches to a similar endeavour (42.).

|

| 30. |

|

| 31. |

|

| 32. |

|

| 33. |

|

| 34. |

|

| 35. |

|

| 36. |

|

| 37. |

|

| 38. |

|

| 39. |

|

| 40. |

|

| 41. |

|

| 42. |

A

musical interlude.

This

sheer variousness of Derain's upsets people who like their artists one-note earnest,

demonstrably serious and preferably, above all, consistent. Equally though, it

would be misleading to value Derain only for his post-modernity, to see him as

an aloof ironist with a quick-hand draw. He is more like a slow-moving

basking shark, gobbling up large swathes of art’s histories, foibles and

potentials as if they were plankton. He’s heavily invested, complex, searching.

He roams the perimeters of painting’s micro-territories, is interested in

processing every aspect of its minutiae as much as its great sweeping themes

and continuities.

Derain was castigated for his own immersion in the multitudes

of his chosen art form, a victim of constrictive notions of authenticity and

sincerity in a world that likes

one-trick ponies. In this he rather recalls Bob Dylan of all people. He certainly

toyed with the identity of the troubadour, particularly in the early Bagpiper picture (which sets-up stall for the second half of his career), conjuring a Dylanesque,

‘eerie childlike world, suffused with a sadness which is adult’ as Rosanna

Warren put it, ('A Metaphysic of Painting: The Notes of Andre Derain', The Georgia Review, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring 1978)), which can become comic or allegorical, romantic or biblical (43.). He liked to tell interviewers that he learned a lot about painting from

watching a sailor decorate his boat, an exercise in self-mythologizing/work-framing

similar to Dylan’s early career fib that he’d worked at a carny freak-show, or

that he’d wanted to be the man who ran the Ferris wheel, (‘They want to make

you have two thoughts’, he noted of the carnival performers, ‘they want to make

you think that they don’t feel bad about themselves and also, they want to make

you feel sorry for them. I always liked that.’) which probably had more to do

with Fellini or Tod Browning than real life, but which calculatingly leads the

reading of the work, expresses obliquely the artists’ mercurial ideals in real

and folksy terms- just as Derain’s roving sailor expresses something about everything from

his brushwork to his devotion to his joy.

|

| 43. |

The

trouble with such stories, even told with a wink, is one is expected

to stick to them. The folk-balladeer turned protest-singer became the

frazzled electric collagist, became, inexplicably, the Nashville

crooner, just as the pioneering Fauve became the neo-classicist became

the senile

recycler. Dylan’s sudden about-face on 1967’s Nashville Skyline- in which his piled-up images and allusions, his

gravel whine, his opacity are cast aside for straightforward, simple words and tunes,

simple sentiments and an affected country croon- finds him positioning himself

apart from the counter-culture just about as far as Derain seemingly pushed himself

from the avant-garde. The irony of these divisive transformations is that they

were motivated by a will to dive ever-deeper into the form.

Dylan would go further on the critically panned Self Portrait (1970)- wherein the songs, many of which are

half-hearted cover-versions, can be super-condensed (All the Tired Horses repeats only the line ‘all the tired horses in the sun, how’m I s’posed to get any ridin’ done?’,

for 3 minutes and 14 seconds), perfunctory in performance, or over-egged in

production- willfully derailing what such a thing (a lavishly packaged double-LP by Bob Dylan

called Self Portrait) should surely

be. Yet the purgative Self Portrait is merely an extreme case of a restless mind burrowing down further into the

conditions of an artform, a systematic interrogation and inhabitation of its ways

and means, an inhabitation of the ballad, the dirge, the standard, the torch

song…etc. Throughout his career Dylan asks himself, what can a

song be? what is a song anyway? where does its songness lie?, questions Derain asks of painting from

picture to picture, mark to mark.

Derain’s

‘late’ works are just as much about testing limits as the early

fauve pictures, yet with an inverted sense of what limit-testing

radicalism can be: a radicalism

of subtlety, radicalism by stealth. Extremity of style, Dylan and Derain

suggest, is no barometer by which to measure a works’ worth, innovation,

uniqueness, etc., apparent 'tameness' of subject no barrier to

profundity. The path to new forms and new ideas does not lead one way.

You

can go in and out through your artform by any door. It can be opened

from

either end. Many ends.

Indeed, the later works are also a kind of fallout from the exploded fauve

canvases that made his name- the pursuit of a certain kind of

realism Derain’s route out of the apparent cul-de-sacs that

he and his colleagues had led themselves into. The jolt of these

irrepressibly

odd, relatively ‘realist’ works is almost equal and opposite to the jolt

of carrying a picture out the studio or gallery and seeing it amongst

the open world; as if he held the fauve pictures up to the window and saw some terrible discrepancy in their condition for which he had to make amends.

........