Art is always the same

- André Derain, De Picturae Rerum

You can have your cake and eat it too

- André Derain, De Picturae Rerum

You can have your cake and eat it too

-Bob Dylan, Lay

Lady Lay

|

| 1. |

It’s possible to read title and picture as being about each subject in turn, about Trees and about Villages, or about this specific combination, this distinct hybrid-subject, Trees-Village. The picture – as part of a larger group of similar pictures by the artist from around the same period, but also from across his career, and also from across the history of the artform (with specific reference to Corot) – explores the weight given to each element, how they interact with one another, the many ways they might do so, and the change in register this can generate (just as it explores ‘the way sky and earth come together’, the infinite permutations of which were where the ‘drama of the countryside’ lay for the artist). It’s a painting of the essential condition of Trees and Villages. An essential condition which is nevertheless infinitely changeable– and changeability in turn part of that essential condition (it goes without saying that this extends to the 'essential condition' of painting).

|

| 2. |

|

| 3. |

|

| 4. |

It’s not just the title which places viewer and artist at a slight remove here. The self-identity of each tree, the perhaps virtually indistinguishable identity of one of these small provincial towns to the next (for the uninitiated, or for the careless traveler), is measured against the relative specificity and genericism of one painting to another (2.-4.), whether they’re landscapes, still lifes, portraits...etc. (5.-11.). Derain constantly measures the generic or generalized against the strikingly singular or singularized. It’s the balance on which his art bobs (and it’s a very ‘art-like’ balance at that).

Various painterly approaches sit side by side. Compare

one tree here to the next- each one different to the last, or existing as an

undifferentiated mass, with schematic indications of trunks and branches. They

are part of a coherent whole, and yet detachable, isolatable. These detachable parts

of wholes are where their modernity, not to say post-modernity, lies. One could

see the story of modernism as the abandonment of air-tight objects, hermetic

worlds, constancy and consistency for contingency, for works which leave punctures,

gaps, blanks, leave the seams showing (which is to say that the picture is also

formally and thematically simpatico). Though to some extent, the practice of painting has always forced its practitioners to generalize or specify, to consider the visual continuity or discontinuity of the world; the individual or composite identities of branch, tree, forest, the relationship of building to neighbourhood to town, mark to illusion to referent, picture to picture to oeuvre... A practice which amounts to something like a partial physical philosophy. Writing on Hinduism in a notebook dated 1909 Derain mused, 'plurality to unity, isn't this the very problem of painting...?'.

Within a Derain picture such as Trees and Villages, specific image meets generic subject. The

picture, and the picture as part of a wider oeuvre, is a complex, primitive computation

system, one impossible to exhaustively explain or comprehend; more

like an ecology. Or: the systems of expansion, consolidation and re-organization

that determined the specific composition of village and forest, tree and

architecture, as seen in the picture titled Trees

and Villages. (Derain deals with this kind of recursion throughout his work

in ways more subtle and charged than in the more widely acknowledged Escher,

for example.)

Indeed ‘trees and villages’ would be an apt metaphor with

which to begin a critical understanding of Derain’s particular body of work,

with its rational and irrational organization, building consciously on

the past but also running with the eccentric growth of old woods, vines and creepers, a labyrinthine

network of excavation, ruination and rebuilding...

|

| 12. |

But Trees and Villages is more than a dry essay in painting’s complexity and contingency. Crucially the picture is also charged with feeling, or at least the possibility of feeling. There’s a loaded cloud waiting to pour down, or to pass overhead. The sky seems heavy, yet the top of the picture seems to evaporate. The weather changes, or the image runs out- we might not register at first whether this top portion is cloud or canvas, is image or periphery. This also occurs at the bottom of the picture, where the signature sits on the edge of the illusion, land and trees a band in the middle, like a memory or a quotation. The signature is a mini-version of the rudimentary tree trunks that swipe flatly in the bushy paintwork, while the clouds are almost inept, barely even cloud-shaped, yet they have a sense of specific weight, motion, illumination. The trees and grass are full, yet appear dry and craggy, sometimes bone-like, aching for the rain.

|

| 13. |

The sun marks the bare tree on the left with a convincing

highlight (12.) – but that highlight can also detach itself into a floating

letter-form, part of the ground level’s particular alphabet of shapes, pointing,

yonder, to the village on the hill in

the distance, as does a wilfully uncoupled squiggle on the far right (13.). Part burning bush, part Belshazzar's Feast, it's a kind of revelatory apparition, a more emphatic version of the kind of 'underwriting' or overwriting that goes on in many Derains, marks that suddenly pull themselves loose, with a sense perhaps in this instance of mystery forces showing their hand. Maybe. Maybe we are just extra-receptive, primed by Derain's complexification/simplification of mark and and tone, just as our senses would be heightened by light and motion in the environment.The branch resembles a slightly a-typical work, Up/Down (1) (14.), by Raoul de Keyser– part glyph or pictogram and close in shape and quasi-mystical register. Similarly the bare tree makes a kind of crutch for a passing cloud, which perches on top like an old nest (almost on the same visual level as the topmost tower of the distant village): it recalls a similarly curious alignment in Poussin's Man Pursued by a Snake (15.), the spindly branches propping up the sky, the portentous cloud a kind of ghostly treetop (a 'Bush of Ghosts').

|

| 14. |

|

| 15. |

Near and yet still impossibly far away, the village is momentarily revealed, but we sense that it will be obscured as we walk on, the trees moving to block it from view like a fairy tale forest. In memory, the picture exists as a country lane or county road. The actual image contains no such road, at least, not a definitive one– only the illusion of a narrow pathway conspired by the trees and the sun, which could disappear should a cloud pass over or the wind change. In any case, the world of the picture is impenetrable, we can go no further.

With its conditions and coincidences of light and shade, in which we are given to read some signs and significance, this is Derain’s treatment of landscape-as-picture-as-life. Chasing down vague pathways, chasing ideals, the acceptance or realization of our particular position or perspective, destinations and journeys, revelation and reticence, calm and turbulence: these things are the evergreen territory of landscape painting which Derain is exploring in Trees and Villages, 20 odd years after the initial modernist period, and which he’d continue to explore for the next 20 odd years. And while all this may seem far too laden for such a modest picture, it is a small piece in a larger body of works which doggedly pursue such things, that explore variation upon variation of painted images and their potential to mean or not.

I

The ‘late’

paintings of André Derain are still overwhelmingly seen as reactionary at worst,

or as exhibits in a slightly dubious narrative of a post-war ‘return to order’

at best. Even the ‘late’ designation is applied to the artist’s work prematurely,

pretty much anything post-fauve (three-quarters of his oeuvre at least) routinely

considered past-its-prime. These are careless readings. For the ‘late’ paintings

are frequently as radical as anything else being done at the time: the pictures

are less a ‘return to order’ than they are part of an expansive and concerted exploration

of different kinds of disorder (certainly

different kinds of disorder to those of the succeeding schools of the

avant-garde). The paintings carry multiple ‘disorders’, maladies, perhaps so

subtle as to be easily miss-diagnosed, put down to unintentional inconsistency.

As early as c.1910 Derain cast aside immediately obvious formal links to the avant-garde- though he remained a close associate of many key players (particularly Picasso, whose eclecticism and frequent tastelessness are not a million miles from Derain, yet somehow not a problem), and an idolatry figure for many aspiring artists, albeit from the distance of his country mansion from the 30’s onwards. His reputation remained above water well into that decade (the paintings’ retroactive ‘classicism’ ultimately deemed ‘ultra-modern’ after much critical humming and hawing), but by the 1940’s had begun to sink alarmingly. By then there was a suspicion as to whether there was simply too much intellectualized ‘referencing’ going on for his own good. This criticism snowballed to such an extent that Alfred Werner, only two years after the artist’s death in 1954, could write that-

As strong as Derain was

intellectually- his contemporaries describe him as having had a superior wit,

and an encyclopaedic erudition- so weak was his character. He wanted power, he

craved money. The dealers were always importunate, and he knew that a picture

was sold for thousands of dollars before it was dry…He no longer imitated the

Old Masters, to pour into them his own spirit; he imitated, he repeated himself

ad nauseum…kept on producing one piece after another, some of them still fairly

good, some very shallow, but all painted with a stupendous technique that

convinced those who loved to be convinced by a famous name. (Alfred Werner,

‘The Fauve Who Was No Beast’, The Antioch Review, vol.16, no.2, 1956).

Werner had escaped to the US after a

year in Dachau, and his distaste may in part have been consciously or

unconsciously magnified by the unfortunate speculation at the time that Derain

had been a collaborator. (Along with several other artists he had travelled to

Nazi Germany to give lectures, idealistically claiming in his defence that

such things were above and beyond nationalistic ideologies, were in fact

necessarily and actively so. It's also worth noting that he was encouraged to make the trip after several

visits from a persistent Gestapo officer, who finally suggested it would be a

good idea to pack a bag.) But Werner’s verdict on Derain is by no means

extreme- a general reek of isolated, old-bourgeoisie conservatism, politically

suspect at worst, commercially driven at best, has tended to cling to the late

work, exacerbated by apologists’ frequent defence that we should value Derain

as he is ‘the most French of French painters’ (in life Derain disparaged such absurdly

petty designations).

If

we take Werner’s position to be the

prosecution, and if we don't wish to be 'convinced by a famous name'

alone, then perhaps a case for the defence should start from the above

charges: the emptiness of intellectualized, ‘smart’ referencing, and the

indiscriminately prolific nature of the artist’s output.

...

The task of art is to level time…A Chinese

philosopher said: ‘I do not innovate. I transmit’. He was a wise man.

- Derain, notebook 1943

The notion of overly intellectualized,

aesthetically bankrupt ‘referencing’ would have been quite alien to Derain. His

copious notebooks, however consciously self-contradictory, are absolutely clear

on his mistrust of the notions of ‘originality’ which had become

prevalent in the early years of the 20th century. For Derain, art was

not a paranoid field of aesthetic brinkmanship, of theories and styles submitted to some kind of critical patent office, but rather a continuum of ideas

and images, a vast resource one could plug into; an open-source software to be

used and adapted. His belief in the eternal friction between the fundamental, essential nature of an artform and the virtually infinite variation of

specific artworks is totally aligned with the preoccupation with ‘type’ and

‘example’ discussed above. It's the motor that drives his work.

Derain’s perceived conservatism was due in part to his apparently taking refuge within the traditionalism of genre, like a hermit crab inhabiting past idioms, holed up as he was in his country estate. Yet

the very traditionalism of genre (landscape, portrait, still life etc., and the sub-categories within these) provided him with a firm base on which to

recombine form and content in ways which would not implode or impede their potential

for meaning (not to say re-meaning), allowed for his radical (visual) re-tellings and debunkings of painting's old stories.

(Artists with a strong and inbuilt, intuitive sense of genre were the ones who

preoccupied him the most, as we shall see.) While the notebooks can slip into

homilies about the ‘universal’, eternal truths and so on, in practice Derain’s focused immersion within the genres and subgenres of western oil painting prevent the work from falling

into trite, brotherhood of man

cultural evisceration. Though he had a keen interest in and collected art from

many non-western cultures, his natural habitat was the European tradition, through which he swam like a fish in water.

Running with the notion of detachment

and cohesion so central to his project, the individual picture was for Derain a

break with the tradition only in so far as it was also a break within his own oeuvre, in so far as the isolated 'subject' was a break with the continuous world, in so far as elements within the picture were building-block

breaks with the picture’s own unity. As if shuffling letters within a word within a

lexicon, Derain was a radical re-configurer for whom art was less the writing of an unending

dictionary than an ever expanding thesaurus: a collection of ‘words’ clustered

around the same general meaning, yet that meaning shifting infinitesimally with

every unit of expression, a concerted effort across generations to approach the

condition of the world from every possible angle, to reach not single definitions but a network of relationships. Art is still and was always the

memory of generations, he wrote.To flick through his catalogue

raisonne, with double-spead after double-spread of row upon row of heads, still life, landscape etc., is to observe a magnetic push and pull between a constantly

reconfiguring set of subjects and images in a kind of dynamic taxonomy or topography.

For Derain, painting was a world of distinct territories– without walls but with misty, mysterious borders, the exploration of which preoccupied him for at least three decades. And he doesn't just explore genre or subject in the conventional sense, but even nebulous 'types' of image within whichever given sub-genre: a certain 'type' of tree-by-road picture, a 'type' of head-turn and shoulder picture, a big-table to the left window-to-the-right still life. A type of elevated coastal/harbour picture (16.), a type of beach-level boat scene (17.) (themselves great subjects for elaborating these notions, hazy borders and horizons vs. robust vessels of venture, exchange and exploration, individual subjects and pictures boats to the artform's ocean). 'Genres' (one could say 'tropes', categories or conventions, but each of these terms casts its own specific shade) of composition, lighting, even 'genres' of mark-making, are explored much more comprehensively and in ways which are much more incisive than in any of his contemporaries (even in the extant that he seems to think of these things as more or less distinct categories – which are also options – at all). Again, the eclecticism of Picasso, say, pales in comparison to the subtlety with which Derain shifts between registers, the sheer variety of his illusionism (merging slapdash handling with sophisticated tones and hues here, letting highly achieved lighting conditions fall on impossibly 'wooden' trees or figures there), the variety of ways in which he slips between old and new idioms.

For Derain, painting was a world of distinct territories– without walls but with misty, mysterious borders, the exploration of which preoccupied him for at least three decades. And he doesn't just explore genre or subject in the conventional sense, but even nebulous 'types' of image within whichever given sub-genre: a certain 'type' of tree-by-road picture, a 'type' of head-turn and shoulder picture, a big-table to the left window-to-the-right still life. A type of elevated coastal/harbour picture (16.), a type of beach-level boat scene (17.) (themselves great subjects for elaborating these notions, hazy borders and horizons vs. robust vessels of venture, exchange and exploration, individual subjects and pictures boats to the artform's ocean). 'Genres' (one could say 'tropes', categories or conventions, but each of these terms casts its own specific shade) of composition, lighting, even 'genres' of mark-making, are explored much more comprehensively and in ways which are much more incisive than in any of his contemporaries (even in the extant that he seems to think of these things as more or less distinct categories – which are also options – at all). Again, the eclecticism of Picasso, say, pales in comparison to the subtlety with which Derain shifts between registers, the sheer variety of his illusionism (merging slapdash handling with sophisticated tones and hues here, letting highly achieved lighting conditions fall on impossibly 'wooden' trees or figures there), the variety of ways in which he slips between old and new idioms.

|

| 16. |

|

| 17. |

|

|

|

|

And in the pictures: can't we still see the drawing

which your eyebrow's dark evanescent stroke

quickly inscribed on the surface of its own turning?

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus XVIII, translated by Stephen Mitchell

H/P

And while Derain speaks in a kind of ‘Old High-Painting’,

he wasn’t exclusive in his sources. However ‘classical’ he gets, however

retrograde, there is always something unmistakably inter-war, 30’s, 40’s about

his work (rather like contemporaneous poets Pound, Eliot, even Cummings, Williams), particularly in the portraits.

Something like Han van Meegeren’s famous

Vermeer fakes from the period, they can occasionally be jarringly ‘Hollywood’ in their

lighting or cosmetics (he was an avid cinema fan), the portraits of a contemporary, popular

‘type’ of look despite their classicism. Across the paintings he’s alive to the

particulars of make-up, the sweep of hairstyles, the application and alteration

of appearances, lipstick, eyeliner, kohled brows, which in turn inform the

depiction of fruit stalks, highlights, handles, tree trunks. All carry his

calligraphic, just-so swipe. (Or he'll purposefully fudge things, the 'forehead' in fig.18. working as a cancellation of the brushmark's inherent predisposition towards natural 'hairline' shapes and behaviours). Throughout the notebooks are various hieroglyphs,

passages of italicized script, Hebrew characters, units of gesture

and communication which are mirrored in the handwriting of his paintings, the marks wriggling free of their cursive bonds, while there is also a sense of 'over-painting' in

many of his later works, a sense that the picture is almost pan-sticked and

eye-linered, the image scrunched, puffed, crimpled, chiffoned.

There's an undeniable parallel drawn between the the application of additional contouring and definition, layering and blending in cosmetics as in painting. The portraits run with notions of illusionism and styling, augmenting and 'improving' on reality. Derain employs slick, skilled marks and accents which paradoxically pop the illusion; the marks themselves give physicality, yet emphasize the pictures' surface, their flatness, bring their physicality and their illusionism up short. He interrogates beauty, just as he celebrates and sabotages it. Throughout his work, in whatever genre, it's rare for him not to leave at least some small sign of human presence or activity– 'beauty' residing in the process of human apprehension and adaptation rather than an inherent property. His world is the perceived/depicted world.

There's an undeniable parallel drawn between the the application of additional contouring and definition, layering and blending in cosmetics as in painting. The portraits run with notions of illusionism and styling, augmenting and 'improving' on reality. Derain employs slick, skilled marks and accents which paradoxically pop the illusion; the marks themselves give physicality, yet emphasize the pictures' surface, their flatness, bring their physicality and their illusionism up short. He interrogates beauty, just as he celebrates and sabotages it. Throughout his work, in whatever genre, it's rare for him not to leave at least some small sign of human presence or activity– 'beauty' residing in the process of human apprehension and adaptation rather than an inherent property. His world is the perceived/depicted world.

|

| 18. |

Again and again Derain finds relationships between the paintings as

physical things and their thematic content. In the case of the portraits, subject

and handling measure the ‘façade’, the surface, against interiority, expressivity, depth. The

faces, or ‘heads’ (they are sometimes more one than the other), themselves provide

a field for endless investigation. They can be psychologically penetrating,

imposing, disarming, or they can be doll-like, impassive, statuesque, mask-like.

(The

number of them worth time and attention belies the sheer volume produced. Compare the way the head fills the frame from one to the other, their tonal variety, their handling etc.).

They seem equally (and remarkably, for

the time) knowing about their own artifices, their own limitations even, the

women depicted frequently falling into certain categories or feminine ‘types’,

playing certain roles which are ostensibly male-defined. Indeed, the 'heads' are potentially

problematic in that they could be seen to objectify women in the same way that

Derain’s paintings ‘objectify’ trees, villages, apples, etc., reducing them merely to examples, specimens.

What can become problematic with painting is

that it cannot help but ‘objectify’, in both senses of the word. It reduces the things of the

world to a series of remote surfaces, presented for aesthetic consideration,

reduces its subjects to their silent appearances. But it also ‘objectifies’ in

the sense of expressing some abstract feeling or notion in concrete form,

literally rendering thought and expression as an ‘object’, exteriorizing and

attempting to make more or less visible and graspable some elusive

condition of being. It’s a queasy thing, particularly in these head paintings, but I would argue that Derain is exploring precisely this problem: that the portraits investigate this biforcated objectification under which painting operates. That they present to the

viewer both the shallow sense of a generic ‘woman’s face’, while expressing

in plastic terms the weird and complex bundle of cultural/personal,

conscious/subconscious associations and conditions which such ‘faces’ might provoke

or mask.

I wouldn’t want to make this an outright

apologism for the pictures’ sexism, to whatever degree, but can only argue that

Derain’s approach toward type and example here is, for better or worse, entirely

consistent with his landscapes, still lifes, et al. That the women’s submission

to, engagement with, personal adaptation, subversion or rejection of these

given ‘genres’ of face-making and self presentation, these given looks and

roles, present a radical re-articulation of his lifelong ‘theme and variation’ fixation.

Derain measures the women’s ‘type’ (as well as type of pose or attitude) against their individuality. As with the landscape and still lifes, they may be a type of something, but they are also strikingly singular, and, as with the paintings in other genres, there is a demand that we spend time to get to know them, to look further and further into their idiosyncrasies. They play with perennial portraiture concerns – estrangement, recognition, the encounter, countenance and character, closeness to or remoteness from the viewer, direct and indirect gazes – which extend as always to the paintings themselves, in their compromised state as pretty (sometimes trashy) surfaces with hidden depths. While these complexities stand out from the many generalized 'portraits' of the time, regrettably the queasiness of painting’s 'objectification' can't help but become amplified in paintings of women (overwhelmingly excluded from technical, professional or social initiation into the field) by men, no matter how well intentioned. But I think we owe Derain the benefit of the doubt. He pursued these faces with the same care and invention that he did all his work– in all its complex shallowness and depth.

In some ways the faces are just too purely and simply strange to be passed off as superficial, mild-erotica (nevermind easily digestible 'eye-candy') as are the wider series of nudes and figures .

And in the pictures: does not the image remain

of your eyebrow's dark streak

scrawled rapidly across the wall of your spin?

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus XVIII, translated by Martyn Crucefix

C

Derain measures the women’s ‘type’ (as well as type of pose or attitude) against their individuality. As with the landscape and still lifes, they may be a type of something, but they are also strikingly singular, and, as with the paintings in other genres, there is a demand that we spend time to get to know them, to look further and further into their idiosyncrasies. They play with perennial portraiture concerns – estrangement, recognition, the encounter, countenance and character, closeness to or remoteness from the viewer, direct and indirect gazes – which extend as always to the paintings themselves, in their compromised state as pretty (sometimes trashy) surfaces with hidden depths. While these complexities stand out from the many generalized 'portraits' of the time, regrettably the queasiness of painting’s 'objectification' can't help but become amplified in paintings of women (overwhelmingly excluded from technical, professional or social initiation into the field) by men, no matter how well intentioned. But I think we owe Derain the benefit of the doubt. He pursued these faces with the same care and invention that he did all his work– in all its complex shallowness and depth.

In some ways the faces are just too purely and simply strange to be passed off as superficial, mild-erotica (nevermind easily digestible 'eye-candy') as are the wider series of nudes and figures .

And in the pictures: does not the image remain

of your eyebrow's dark streak

scrawled rapidly across the wall of your spin?

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus XVIII, translated by Martyn Crucefix

|

| 19. |

C

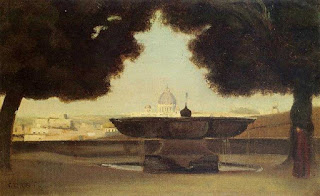

It’s probably worth mentioning at this

point that perhaps the single biggest influence on Derain (and Derain was a

wide and voracious sea-sponge after all) was Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.

Corot, the great landscape painter,

the bridge between the classicism of Claude and the empiricism of the impressionists,

was a natural Derain touchstone. It’s his by turns diffused, silvery, flecked and silky,

by turns buttery and saturated, olive-oily light that we see again and again

throughout Derain’s landscapes (19.);

Corot’s oil-sketch strokes and swipes, allowed to increasingly infiltrate

‘finished’ canvases that lead to Derain’s surface marks; his predilection for

off-set graphic blocks and shards of light or shadow that lead to Derain’s

scattered jigsaw flecks and characters (20., 21.). The debt owed to

the older artist’s coastal/harbour scenes is undeniable (22., 23.).

|

| 20. |

|

| 21. |

Indeed Derain would return to the places

where the breakthroughs of Corot, Rousseu, Courbet and the rest were made and modern

French painting born. Part archaeologist, part pilgrim, he would haunt the

landscapes of Fontainebleau, Barbizon, Granville– as the film documentarian Mark

Cousins said of himself and movies, Derain wanted to be ‘close to the contours’

of painting.

|

|

| 22. |

|

| 23. |

However there was a hidden side to Corot’s output that remained largely unknown until after his death: just as influential on Derain were the artist’s figure paintings, works carried out as a kind of private project between the celebrated landscapes (Corot described them as a necessary break, a holiday from his main activities which he reportedly looked forward to).

With variation upon variation of

dreamy figures in repose, these pictures represent a private research which

must have struck a chord with Derain. He would surely have been exposed

to Lady in Blue (24.) the first of Corot’s

figures to see the light of day, at the Exposition of 1900. There’s definitely

a Derain-ish inconsistency between the picture’s top and bottom half, firmer

modelling dissolving into feathery strokes.

In fact, the overwhelming majority of Corot’s figure paintings contain some moment of pictorial disruption, carry some deformity; an inconsistency of draughtsmanship between, say, one hand and the other, the head and the shoulders, malformed limbs hanging from dresses. It’s easy to put this down to simple clumsiness (or carelessness in that they were never intended for exhibition) but its these elements which allow them a startling modernity. They prefigure the oddness of Derain’s semi-classicized faces, all shadowed, sculpted eyes, or the elisions of his anatomy, the biomorphic distortions of Picasso, etc. The inconsistency of Lady in Blue later becomes the jitteriness of The Beautiful Model (1923 (25.)), with it’s oddly straightened, bookend back, which in turn reacts with the sudden caligraphic swipe against the belly button, creating an erotic, jerky frisson.

|

| A.D. |

In fact, the overwhelming majority of Corot’s figure paintings contain some moment of pictorial disruption, carry some deformity; an inconsistency of draughtsmanship between, say, one hand and the other, the head and the shoulders, malformed limbs hanging from dresses. It’s easy to put this down to simple clumsiness (or carelessness in that they were never intended for exhibition) but its these elements which allow them a startling modernity. They prefigure the oddness of Derain’s semi-classicized faces, all shadowed, sculpted eyes, or the elisions of his anatomy, the biomorphic distortions of Picasso, etc. The inconsistency of Lady in Blue later becomes the jitteriness of The Beautiful Model (1923 (25.)), with it’s oddly straightened, bookend back, which in turn reacts with the sudden caligraphic swipe against the belly button, creating an erotic, jerky frisson.

|

| 24. |

|

| 25. |

|

| 26. |

The women (they are mostly women, yet

there are occasional male figures, humorously reclining (26.)) look to be made-up, or

at least largely composite in character. There’s a disconcerting feeling of

unreality to them, as if we’ve suddenly come across the people that inhabit Corot's

peculiar painting-land, the distant figures from his dappled landscapes seen up

close, and a listlessness to many of them, as if their minds have been left half-formed. Many resemble novelty photographs, the figures posed against fake

backdrops with a ledge or a rock to lean on- fantasy images (even Derain's landscapes or still lifes are allways somehow 'made-up', fantasy landscapes, fantasy still lifes).

|

| A.D. |

In some ways both

Corot and Derain recall Fragonard’s figures

de fantaisie of the previous century (27., 28.)– pictures executed almost for the sake of it, excuses for paintings. Knowingly over-the-top, knowingly 'painted',

Derain’s pictures can similarly morph into outré, neo-rococo territory, can

play painterly dress-up and parlour games.

|

| 27. |

|

| 28. |

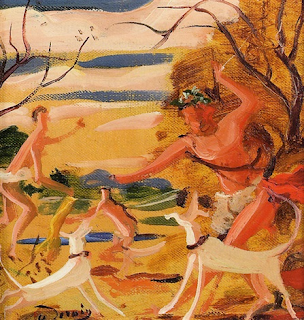

Scenes of hunts, across country parks

or formal gardens can in turn metamorphose into pseudo-quattrocento, pseudo-mythological

Bacchanals, creepy and haunting in the way they re-imagine a certain

kind of over-cooked painting (29., 30., 35.). Their painterly reinvention recalls that of Bob

Thompson in the 1960s (31.- 34.) crackling

with energy, super-conscious, savvy and child-like at the same time, exploring the implications of 'plurality/unity', stasis and protean materiality, raised by the patchwork-quilt composition of Renaissance or Baroque painting.

|

| 29. |

These are rarely close to the kinds of arcadia painted by his contemporaries (Matisse’s Luxe, Calm, et Volupté, La Danse etc.), often carrying instead a feeling of immanent menace. Some have a child-like picture-book or nursery rhyme quality, (One man went to mow, went to mow a meadow (36.), A sailor went to sea sea sea to see what he could see see see (40.)). But even The Bagpiper at Camiers (41.) is more a kind of mesmeric Pied Piper, his playing twisting the road ahead like a charmed snake. These pictures can vary between patchy, dry Cezannisme, Jack Yeats-ish impasto, even a kind of rudimentary, ‘armature’ quality that recalls Lowry (37.-39.) (indeed Lowry’s and Derain’s series of ‘Heads’ could be seen as the results of two differing temperament’s approaches to a similar endeavour (42.)).

|

| 30. |

|

| 31. |

|

| 32. |

|

| 33. |

|

| 34. |

|

| 35. |

|

| 36. |

|

| 37. |

|

| 38. |

|

| 39. |

|

| 40. |

|

| 41. |

|

| 42. |

A

musical interlude.

This

sheer variousness of Derain's upsets people who like their artists one-note earnest,

demonstrably serious and preferably, above all, consistent. Equally though, it

would be misleading to value Derain only for his post-modernity, to see him as

an aloof ironist with a quick-hand draw. He is more like a slow-moving

basking shark, gobbling up large swathes of art’s histories, foibles and

potentials as if they were plankton. He’s heavily invested, complex, searching.

He roams the perimeters of painting’s micro-territories, is interested in

processing every aspect of its minutiae as much as its great sweeping themes

and continuities.

Derain was castigated for his own immersion in the multitudes

of his chosen art form, a victim of constrictive notions of authenticity and

sincerity in a world that likes

one-trick ponies. In this he rather recalls Bob Dylan of all people. He certainly

toyed with the identity of the troubadour, particularly in the early Bagpiper picture (which sets-up stall for the second half of his career), conjuring a Dylanesque,

‘eerie childlike world, suffused with a sadness which is adult’ as Rosanna

Warren put it, ('A Metaphysic of Painting: The Notes of Andre Derain', The Georgia Review, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring 1978)), which can become comic or allegorical, romantic or biblical (43.). He liked to tell interviewers that he learned a lot about painting from

watching a sailor decorate his boat, an exercise in self-mythologizing/work-framing

similar to Dylan’s early career fib that he’d worked at a carny freak-show, or

that he’d wanted to be the man who ran the Ferris wheel, (‘They want to make

you have two thoughts’, he noted of the carnival performers, ‘they want to make

you think that they don’t feel bad about themselves and also, they want to make

you feel sorry for them. I always liked that.’) which probably had more to do

with Fellini or Tod Browning than real life, but which calculatingly leads the

reading of the work, expresses obliquely the artists’ mercurial ideals in real

and folksy terms- just as Derain’s roving sailor expresses something about everything from

his brushwork to his devotion to his joy.

|

| 43. |

The trouble with such stories, even told with a wink, is one is expected

to stick to them. The folk-balladeer turned protest-singer became the frazzled electric collagist, became, inexplicably, the Nashville

crooner, just as the pioneering Fauve became the neo-classicist became the senile

recycler. Dylan’s sudden about-face on 1967’s Nashville Skyline- in which his piled-up images and allusions, his

gravel whine, his opacity are cast aside for straightforward, simple words and tunes,

simple sentiments and an affected country croon- finds him positioning himself

apart from the counter-culture just about as far as Derain seemingly pushed himself

from the avant-garde. The irony of these divisive transformations is that they

were motivated by a will to dive ever-deeper into the form.

Dylan would go further on the critically panned Self Portrait (1970)- wherein the songs, many of which are

half-hearted cover-versions, can be super-condensed (All the Tired Horses repeats only the line ‘all the tired horses in the sun, how’m I s’posed to get any ridin’ done?’,

for 3 minutes and 14 seconds), perfunctory in performance, or over-egged in

production- willfully derailing what such a thing (a lavishly packaged double-LP by Bob Dylan

called Self Portrait) should surely

be. Yet the purgative Self Portrait is merely an extreme case of a restless mind burrowing down further into the

conditions of an artform, a systematic interrogation and inhabitation of its ways

and means, an inhabitation of the ballad, the dirge, the standard, the torch

song…etc. Throughout his career Dylan asks himself, what can a

song be? what is a song anyway? where does its songness lie?, questions Derain asks of painting from

picture to picture, mark to mark.

Derain’s ‘late’ works are just as much about testing limits as the early

fauve pictures, yet with an inverted sense of what limit-testing radicalism can be: a radicalism

of subtlety, radicalism by stealth. Extremity of style, Dylan and Derain

suggest, is no barometer by which to measure a works’ worth, innovation,

uniqueness, etc., apparent 'tameness' of subject no barrier to profundity. The path to new forms and new ideas does not lead one way. You

can go in and out through your artform by any door. It can be opened from

either end. Many ends.

Indeed, the later works are also a kind of fallout from the exploded fauve

canvases that made his name– the pursuit of a certain kind of realism Derain’s route out of the apparent cul-de-sacs that

he and his colleagues had led themselves into. The jolt of these irrepressibly

odd, relatively ‘realist’ works is almost equal and opposite to the jolt of carrying a picture out the studio or gallery and seeing it amongst the open world: as if he held the fauve pictures up to the window and saw some terrible discrepancy in their condition for which he had to make amends.

........

SL

Ever since that day, or I might even say the moment of that

day in 1936, when a chance sight of one of Derain’s canvases in a gallery –

three pears on a table silhouetted against a vast black background – arrested my

attention and impressed me in a completely new way (it is there that for the

first time I really penetrated beyond the immediate appearance of one of Derain’s

paintings), ever since that moment all Derain’s canvases without exception, the

best of them as well as the less good, have impressed me and compelled me to

look at them for a long time and search what lay behind them…

–Alberto Giacometti, letter, 1957

–Alberto Giacometti, letter, 1957

Total object,

complete with missing parts…Question of degree…All I wish to suggest is that

the tendency and accomplishment of this painting are fundamentally those of

previous painting, straining to enlarge the statement of a compromise...

–Samuel Beckett, 3 Dialogues

–Samuel Beckett, 3 Dialogues

|

| 44. |

Still Life

with Pears (44.) is a series of little bells ringing in

sequence, as if on a butler’s wall. Tinkling, tolling out some small message from

upstairs. It’s also a discarded pair of disguise spectacles, with pear nose and

ears attached, spoon for a moustache á la Acrimboldo. Cut pear-slice and

scooping spoon-head are two perfectly split halves, white highlight winking at

brown pip, microphone and receiver in a rudimentary form of material telemetry,

endlessly chasing one another like the cups of an anemometer. Like many

works in the genre, this still life is part hokey science experiment, part

conjuring trick, part schoolroom prop. The spoon-handle underlines the whole

thing, just as the signature is underlined – another name for a name being one’s

‘handle’ – a handle being that with which something is grasped, or understood,

mediated, transferred. It exists on a plane – and advertises a presence – possibly

sacred or possibly mundane. All 6 senses are brought into play, though it’s

an imperfect transmission. The picture is faulty. The ellipses of the glasses

are way off, yet their highlights are close enough and in the right general

area to convince the screwed up eye, or the snatched or distant glance. As much

as it’s a perfectly compromised representation of reality it is also a

perfectly compromised representation of 17th century still life. The

glasses manage to be delicate, exact, and yet totally inept at the same time. We

are not sure to what extent they are ‘real’ or ‘painting-real’. Painting is the

only art capable of doing exactly this. Prose or poetry are always verbal

approximations, working via metaphor (imagine trying to write that the shapes of observed glasses are waywardly-off); sculpture would have to literally distort them in 3 dimensions, would be too obviously 'wrong', or would register them plainly as misshaped objects; painting has the capability of rendering

things more or less ‘truly’ in their appearances, as well as the capacity to

waiver such verisimilitude, at will and by degree.

Alberto Giacometti is

an artist of such unrelenting seriousness that when he speaks we tend to

listen. His opinion of what counts counts. So when he writes of how Derain’s

pears had such an affect on him critics tend to take note. In fact, he did his

friend a great favour in leaving a few breadcrumbs scattered throughout letters

and memoirs (sample: ‘Derain excites me more, has given me more and taught

me more, than any painter since Cezanne; to me he is the most audacious of them

all.’), even if they are rarely followed with much critical gumption. His final

verdict on the artist, though, captures succinctly and with a lightness of

touch everything of Derain’s elusive simplicity and complexity–

…perhaps he did not intend to do much more than to capture a little of

the appearances of things, the marvelous, fascinating, inscrutable appearance

of everything that surrounded him.

To capture a little of the appearance of things. The crucial phrase here is a little.

The process of deciding which bits

of appearances to capture, and how, is as old as painting. Derain’s absorption

in art of the past was in part a preoccupation with those bits of appearances

which had been captured or preserved, or which had been considered worth

preserving or capturing, at a given time, with a mind towards which bits of

appearances he could select as a conscious person living in the present, from

moment to moment, picture to picture.

|

| 45. |

One of the most prized works in his

extensive private collection was Still life

with cheesestack, bread napkin and pretzels (c.1615) (45.)

by Clara Peeters- a picture which plays with the relative solidities of its own

appearances, the various foodstuffs undergoing a certain re-moulding and solidifying,

with cheese ‘cases’ and knotted pretzel ‘shells’ to match the decorative bowls and

vessels, the lidded tankard becoming a comical sentry guarding the edible hoard

of an edible palace (it’s easy to miss the red tankard’s sculpted face and

metal ‘helmet’), mirrored and perhaps mocked on his opposite side by the stealthy,

barely-there glasses (things apparently 'made' only of light, with an implicit acknowledgement that all the phenomena depicted in the picture are but a set of interactions with coloured light, rendered in transparent 'glazes'). In everything from its lighting to its contrivances to

its metaphysics it’s consistent with Derain’s approach to still life, his

latent left Bank existentialism, not to say absurdism.

Still life of the 17th century, particularly Dutch still life, seems to have haunted his visual imagination. Selections of foodstuffs, vessels, tools, utensils lit against a dark background, half-offering half-equation, wherein objects emerge with the clarity of an impossibly clear thought, as if from some theoretical space, resting on tables of the mind; or like celestial bodies seen through a telescope, carrying with them a certain notion of ‘appearances’ which can contain the real and the supernatural, the deeply secular and the deeply numinous; a notion of ‘illumination’ in all its metaphysical dimensions.

Indeed the dabbed-on white highlight is another

Derain fixation. Andre Breton would later recall he ‘spoke with emotion of this

white spot which some 17th century Flemish and Dutch painters used

to enhance a vase, a fruit… The object I

am painting, the being before me, only comes to life when I add this spot of

white’. This divine spark, this tap of the fairy godmother’s wand, comes in

many shapes and forms across the still lifes- sometimes it sits disruptively on

top, sometimes it’s actually absent altogether, while other pictures run wild

with the highlight as a kind of outline, pictures that look more like drawings

on blackboards (46.-48.).

|

| 46. |

|

| 47. |

|

| 48. |

If drawings tend to be things made of dark lines

on light backgrounds then painting, working from the opposite polarity, is a

process of ‘bringing to light’ – part of its essential nature a coaxing of

appearances through light. Similarly,

if the black word on the white page is something of a cypher for the

exteriorization of thought, then perhaps the dark liminal void against which

objects appear in still life is a metaphor for the interior mind.

From blackboard to theatre, it’s shorthand for a space cerebral, propositional,

potential. Derain does interesting things like move the ‘frame’ across this

seemingly infinite black void-room to suddenly find a window of blue sky (49., 50.),

those hinted-at light sources from the 17th century, though we

suspect these could be rolled-up like cartoon roller-blinds with a summary

yank. The two versions of this picture have the light coming in in opposite

directions, neither of which seem to involve the window. Again the mysterious light

source is off-stage, the objects lit practically by our looking. Painting makes-up

its own clear and distinct

ideas, its own moment to moment versions of appearances, and Derain

delights in the picture to picture, gesture to gesture authority he can wield,

the sheer inconsistency illusionism can get away with.

|

| 49. |

|

| 50. |

Constancy, inconstancy and inconsistency are the Derain preoccupation. They arguably

find their most extreme expression in the condensed object world of the still

lifes, the purest distillation of his art.

The pictures revel in their own protean state. Existing side by side are

passages of amorphous nothingness, dumb literalness and flickers of

extraordinary illusionism. The glass in Still

life with a glass of wine (c.1928) (51.) is a thing of black and white outlines filled with real liquid and

penetrated by real light; Plate of fruits

with a knife (c.1944-48) (52.) is a

catalogue of marks, bold gradients, buttery metal, alternately springy and

dried leaves; Fruits and cutlery (c.1948-1950)

is brittle, blown and desolate, totally flat and insubstantial but for the

amazingly scooped-out bowl, the very picture of hollow yearning (53.); Still life with pears (1939) (54.) is an oddly porky, gammon-joint of a

picture, grapes and pears more like peas and cutlets, suddenly introducing a

note of savoury saltiness.

|

| 51. |

|

| 52. |

|

| 53. |

|

| 54. |

The results of the fauve years are there in these diverse works. They

breathe. Marks, whether highlights, or patches of tone,

of light or shade or texture, are at once descriptive, cohesive, justified; and yet they also tend to sit

just a little up and off from their objects of reference. The individuated marks

on the paintings hover a tad, like elements in an exploded model. Derain is something

like a master cabinet maker who wants you to see the join: a) to demonstrate

the beauty in the made-ness and considered-ness of the thing, and b) to see the

cabinet, but also to see the cabinet and the space within differently. To open

up the metaphoric potential in its nooks. All panels, doors and

drawers are left with a 3mm gap of breathing space, the whole thing a bit, but

only a bit, like an orrery, a bit, but only a bit, like a fine old house, the boarded-up

shutters prized apart. Nothing touches, quite, in Derain’s queer estate. Each thing,

rather, considers that which it is next to; the apple considers the bowl, and

the bowl considers the apple; the shadows of each do the same; as do the white

spots cast from the absent window. All things hover in relationships

of inalienably connected distinctiveness – a fundamentally painting-paradoxical worldview.

F.

Life is just a bowl of cherries,

Don't take it serious, it's too mysterious,

You work, you save, you worry so,

But you cant take your dough when you go, go, go…

- Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries, Ray Henderson & Lew Brown

There's a cool wind blowing in the sound of

happy people

At a party given for the gay and debonair

There's an organ blowing in the breeze

For the dancers hid behind the trees

But I ain't never gonna see

What’s shakin’ on the hill...

At a party given for the gay and debonair

There's an organ blowing in the breeze

For the dancers hid behind the trees

But I ain't never gonna see

What’s shakin’ on the hill...

-What’s Shakin’ on the Hill, Nick Lowe

Back on that country road that probably isn’t really a road, Derain stands contemplating the appearance of the world. Like Calvino’s Mr. Palomar, trying his best to describe and to understand then moving on to the next thing, who watches waves hit the shore and believes 'as soon as he notices that the images are being repeated, he will know he has seen everything he wanted to see and he will be able to stop’. The trouble is, the images do repeat, but they are never quite the same. It’s also pretty hard to say where one image ends and the next begins. We have reached the end, have just finished dealing with Derain’s still lifes. Yet within this body of still lifes are also his ‘landscape-still-lifes’, that odd hybrid genre, scenes of abandoned picnics or baskets of fruit laid out in the countryside (55.-57.) (which recall Courbet particularly (58.)). And if we take the country road we’ll end up at the village, and in the village will be rooms, and in the rooms will be people and objects and windows, and outside the windows will be a view of the sea, and…

|

| 55. |

|

| 56. |

|

| 57. |

|

| 58. |

And again, even within the larger, more obviously ‘staged’ pictures where

Derain rallies his multiple subjects there is a sense that they compound

rather than explain away the mysteries of the landscapes, still lifes,

portraits. The Painter and his Family (c.1939) (60.) piles subject on subject, which, as with Geneviève à la pomme (1937-38) (59.) again takes place in the 17th century darkroom, rather like Derek Jarman's Wittgenstein a theatrical, allegorical, rhetorical space. Or a picture like Nude on a

Sofa (62.) can contain within it callbacks

to all sorts of pictures; the hair and cosmetics of the ‘heads’; the creases on

the drape to the right a kind of ghost image of The Back (64.); the

pink and white fabrics recalling his frequent dual-headed flower motif (61.-63.), the lower white one becoming a kind

of lapdog. Each element has a complex independent existence. Frequently his

models look bored , uncomfortable or distracted (see Geneviève rolling her eyes at the apple, at her own 'painting' pose, or the broken wrist of the nude on the sofa)– that try as he might to get

people, objects and places to play along, they are not totally ruled or understood

by him, just as he himself is a medium through which the consciousness of Painting

passes. There is a sense that so much as he can play with the plasticity of

paint, the world refuses to be captured, to let itself be known. That everything, even his own artform, has

a mysterious life of its own.

|

| 59. |

|

| 60. |

|

| 61. |

|

| 62. |

|

| 63. |

|

| 64. |

Derain's vast oeuvre ends up, finally, as an eloquent exploration of the almost creepy fecundity, aliveness and multiplicity of the knowable-unknowable world. One of his most charged subjects is the abandoned picnic. He picks over it like a child (or perhaps a creepy crawly, an ant?) who’s come across some artefact of human affairs beyond its understanding and has hit a wall. Detachment, mystery, melancholy, potency, pleasure, impenetrability. Whether he is painting a landscape, a coast, a face, a pear, it’s the same feeling.