We must resign

ourselves to the fact that we are outsiders, condemned for ever to haunt the

borders and margins of this great art... Words are an impure medium; better far

to have been born into the silent kingdom of paint.

-Virginia Woolf, Walter Sickert: A Conversation

For Walter Richard Sickert, the world is a series of quietly passing

images; deserted street corners, beds and oceans to be gotten in and out of,

rooms to be left; stages, stalls and theatres to watch and play, for a while; doors

and shopfronts to be opened and closed, backdrops to be rolled up; frames to be

occupied and vacated.

For all his acknowledged formal inklings of later modernism, the images

alone convey a sense of time passing, of the world as it ‘is’ fragmenting, changing

and disappearing just as he pictures it. Maybe even the feeling that he is

already turning to look away. Where Sickert differs from official modernist narratives is partially his

emphasis less on the forward march of progress than on the acceleration of that

which has passed - he seems to intuit the speed at which modern life is

changing and the rapidly narrowing gap between past, present and future,

squeezing ever-greater quantities of the faded or redundant, nostalgic or

poignant or quaint from the shrinking present. Perhaps it’s more than a quirk of his technique that the pictures look

old-on-arrival (while being daringly progressive and ‘new’ in composition or

content, or in how they negotiate their sources).

Indeed, across his long career Sickert establishes something much

closer to post-modernism within his highly conscious explorations of pictorial

language and form, his appropriation of photography in the late portraits, Victorian

illustrations in the so-called ‘Echoes’ of the 20’s and 30’s etc.Yet the late works have often been neglected – respected, yes, for

their conceptual savvy/innovation, but seldom explored with the same attention

to form and content as the early pictures that made his reputation (the ‘Camden

Murderer’ nudes particularly, which have a more obvious lineage in Bacon, and

more superficially in Freud, Auerbach etc.), or at worst seen as endemic of an

overall decline into commercialism, ineptitude and poor taste generally. When

the late works are celebrated (in the RA show of ’93, or in the Hayward show, Late

Sickert, of ’82) critical commentary tends to isolate them from the full body

of his oeuvre – citing his re-emergence after listlessness and illness in 1927

as ‘Richard’, after a lifetime as Walter Sickert, and practically treating him

as a separate artist.

Yet the late pictures continue many of the threads of his earlier

celebrated work, pointing back to his own career and to his immediate

predecessors (particularly Daumier), revisiting, re-evaluating and

re-synthesizing his old motifs as much as they point to the future (and further

afield, to Jack Yeats, Beckett, Katz...). The best of these works complicate

and extend the oeuvre’s emotional range as much as they complicate Sickert’s relationship

to time and the present. For as much as they are a series of quietly passing

images, a quietly passing vision, they are also images of a quietly passing

world.

.

Just as dinner was announced, somebody asked: "But when were

picture galleries invented?", a question naturally arising, for the

discussion about the value of coloured lights had led somebody to say that in

the eyes of a motorist red is not a colour but simply a danger signal. We shall

very soon lose our sense of colour, another added, exaggerating, of course.

- Virginia Woolf, Walter Sickert: A Conversation

Virginia Woolf begins her essay Walter Sickert: A Conversation with the

notion of pictures’ place as ballast against a changing world:

...buildings are changing their character because no one can stand

still to look at them... This naturally led to the question when picture

galleries were first opened, and as no precise answer was forthcoming the

speaker went on to sketch a fancy picture of an inventive youth having to wait

his turn to cross Ludgate Circus in the reign of Queen Anne. "Look,"

he said to himself, "how the coaches cut across the corners! That poor old

boy," he said, "positively had to put his hand to his pig-tail. Nobody

any longer stops to look at St. Paul's. Soon all these swinging signboards will

be dismantled. Let me take time by the forelock," he said, and, going to

his bank, which was near at hand, drew out what remained of his patrimony, and

invested it in a neat set of rooms in Bond Street, where he hung the first show

of pictures ever to be displayed to the public... Perhaps, said the others; but

nobody troubled to verify the statement, for it was a bitter cold night in

December and the soup stood upon the table.

Contrary to the ‘speed’ of modern life, Woolf introduces the idea that Sickert’s

pictures- for all their tempered modernism- are also trinkets and keepsakes,

mementos, unashamedly sentimental in nature if not in coolness of execution

(she later contrasts the pitfalls of a novelist’s fall into sentimentality

versus the painter’s ability to make the pathos in an image implicit, to

present rather than tell).

Shrewdly Woolf also seems to

deal with the fanciful folk history and nostalgia of Sickert’s Echoes (though

they remain unmentioned, directly at least) through a whimsical, caricatured history

of the picture gallery, using a kind of invented or inverted past vernacular

from an English Neverwhen (the bank being ‘near at hand’ is a wonderful detail)

and setting up the two themes of Sickert’s late work: the passing world, and

the popular image/form.

.

|

| 1. |

So just let me be beside the seaside!

I'll be beside myself with glee

and there's lots of girls beside,

I should like to be beside, beside the seaside,

beside the sea!

I'll be beside myself with glee

and there's lots of girls beside,

I should like to be beside, beside the seaside,

beside the sea!

- popular song, John A. Glover-Kind

Oh this is a happy day!

-

Samuel Beckett, Happy Days

Sickert began painting what he called his ‘English Echoes’ in the late

1920’s- more or less direct copies of prints and illustrations from popular

engravings and periodicals of the previous century (the first was apparently

copied from a biscuit tin or pot lid).

They frequently feature roughly painted black outlines, looping and

calligraphic, or patches of lurid colour exaggerating the effects of

reproduction or cheap hand-tinting. The subjects range from picture postcard

seaside towns (Margate in the time of Turner) to chocolate-box carriages, Dickensian

dens, dances and drawing rooms, farce and melodrama, Restoration comedy,

frolics frocks and hedgerows etc.

At the time responses were mixed (though the Echoes sold as well as any

of his work). While the artist William Rothenstein saw them as ‘a witty

commentary on the nineteenth century, on its charm and absurdities’ and noted

that Sickert’s ‘mind remains ever alert to see the possibilities most artists

neglect’, others saw them as idiotic. They’ve gone in and out of favour ever

since- either as late (weak) work to be indulged in, or as cynical

money-making/time-saving exercises. It doesn’t help that Sickert observed,

typically offhand, ‘It’s such a good arrangement; Cruikshank and Gilbert do all

the work, and I get all the money!’- but surely, with an artist at once so

restlessly inventive, serious, and dry in wit as Sickert, to take this comment

at face value or to allow it to lead critical judgement is surely a mistake and

a loss.

Not all the Echoes are great- I suspect they become tiresome in large

groups- but they obviously fascinated him (for many years he had been known to

spend hours rifling through old copies of the London illustrated News and so

on). Crucially he never disguises but rather emphasizes the source material-

they are always very much paintings of drawings, paintings of pictures (with

the squared construction lines left intact- playing, as he did throughout his

oeuvre, with notions of copying, sketching and ‘finish’ and their relationship

to a real world of people and things).

Even such seemingly quaint frivolities as The Two Lags (After John Gilbert) (1.) though, reward longer consideration- the central figure in grey coat and top-hat mirror-imaged on the far right as a comical/ghostly sketch (playing with typical Sickert notions of doubling and mimesis, playing one's part, as does the woman on the far left, her bustle an inversion of her parasol, the structured dress and corset an elaborate piece of stage-rigging), the absurdities of scale, background figures seemingly standing on shoulders, emerging from hats, or with apparent centaur legs- the painting seems to be about the sheer toytown merry-go-round qualities of the world it refers to, the outre exaggerations of Victorian society's representations of itself (thus also it knowingly critiques, fondly, the kind of nostalgia for Victoriana that was going on in the early 1930's, of which the painting itself is a qualified example).

Even such seemingly quaint frivolities as The Two Lags (After John Gilbert) (1.) though, reward longer consideration- the central figure in grey coat and top-hat mirror-imaged on the far right as a comical/ghostly sketch (playing with typical Sickert notions of doubling and mimesis, playing one's part, as does the woman on the far left, her bustle an inversion of her parasol, the structured dress and corset an elaborate piece of stage-rigging), the absurdities of scale, background figures seemingly standing on shoulders, emerging from hats, or with apparent centaur legs- the painting seems to be about the sheer toytown merry-go-round qualities of the world it refers to, the outre exaggerations of Victorian society's representations of itself (thus also it knowingly critiques, fondly, the kind of nostalgia for Victoriana that was going on in the early 1930's, of which the painting itself is a qualified example).

Possibly the single best of them, and the one that manages to most

successfully read at once as both a painting of a ‘type’ of illustration of a

type of set-up or situation, and as a sensitive, complex and haunting painting

in its own right, is Summer Lighting after John Gilbert (1932) (2.).

|

| 2. |

In a way it’s a picture rife with cliché; the gnarled leering trees and

the approaching stranger, the encounter on a sea cliff, wind in the bonnet, the

safety/restrictions of the town impossibly far away, down below in the

distance; it brings with it a host of associations from melodramatic fiction

both romantic and trashy (the wooden fence can also read as a bench, recalling

the daylight-gothic scene where Count Dracula is first encountered on the

cliffs of Whitby, and indeed Sickert studied acting under Sir Henry Irving, an

acknowledged inspiration for the character). It’s a charged scene- charged with

these clichés as much as the actual dramatic incident depicted- and pretty

clear why Sickert should latch on to it.

But beside those clichés (in spite or because of them?), the painting

has its own kind of power. The powdery light and finish are part of it- with

the strongly contrasting, solid black- a kind of dazzled winter/early-spring

brightness, queasy blue and white. It’s slightly retinal, like a burned

after-image which, in a way, it is.

The colour is drained of life

and warmth, yet the paint vibrates, starry-eyed, or as if the whole thing is

made of the bleached, rustling grass that hangs on the cliffside. There is a

sense of vertigo, heady high air, dizziness after the climb and the sudden sun. It’s a painting of a picture whistled down a sea wind, a ghost of a

memory of a memory.

In this particular Echo, the source image and painting manner fuse with

one’s own experiences and memories, cultural and personal. Part of its

wooziness is the way it see-saws between coming across like a painted

representation of an actual occurrence, before collapsing into a series of

paper cut-outs, stage flats and curtains (there’s even a sense of the magnesium

flare of a camera flash). The main figure of the woman in the foreground can

seem as much troubled by the approach of the stranger as she is troubled by the

reality of her surroundings- she seems to consciously emerge somewhat from the

fakery of what’s around her, tentatively reaching out to touch the fencepost. Whether

by accident or by design, her shadow falls on the post (as it should) but also

seems to continue to the height of the tree- which again pulls the depicted

space up short, as if her shadow is falling on a backcloth, or a

false-perspective hill.

There’s an old episode of The Prisoner where No.6 finds he’s been

living in a fake western town, talking to carboard cut-outs- the dark turn of Summer

Lightning is almost like the ‘last episode’ of the Echoes, when the characters

are for a moment struck by the unreality of their painted world. Indeed, the

echoes leave certain threads hanging that won’t really be picked up again until

the 1960’s’ obsession with (constructed) Victoriana, or even the animated

sequence in Mary Poppins when the characters enter the reality of a pavement

chalk drawing, an Edwardian summer world of bandstands and boaters that fades

when the rain comes to wash it away.

|

| 2. |

This kind of play on illusionism

in Sickert’s work is already there in the early music hall pictures such as The Lion Comique of 1887 (2.), where

the artificial backdrop behind the performer doubles back towards convincing

illusion within the reality of the painting. It’s entirely logical within the

terms of this picture that we might be looking out from an artificially-lit

veranda or bandstand onto a real lake (as we might be in an over-the-top, schmaltzy

Sargent of the period, the up-lighting of his Spanish Dancer, the twilight

gatherings on the balconies of the Luxembourg Gardens), yet we intuit from the

very slightly over-cooked blue of the moonlight and the angle of the balcony

arches that this is not the case. The performer even seems to point back at it

with his thumb, laughing at his own backdrop, perhaps already dwelling on the

after-show blues, the little yachts rolled up like his stiff-collar. Contemporary

reviews made a negative of the backcloth/landscape, flat/spatial ambiguities in

The Lion Comique, but it’s hard not to see this

ambiguity as an essential part of the picture’s subject: the jarring tonal

effects of the music hall routine, the singer alternating between ballads and

broad comedy, sincerity and self-consciousness, earnestness and irony.

.

On the outskirts of every agony sits some observant fellow who points.

-Virginia Woolf, The Waves

What makes Summer Lightning doubly interesting is its relationship to

the earlier picture (3.) The Front at Hove (1930, original title ‘Turpe Senex Miles

Turpe Senilis Amor’, or ‘An old soldier is a wretched thing, so also is senile

love’, a quotation from Ovid which makes the situation depicted explicit). The

two paintings are too close in style and subject to be coincidence.

|

| 3. |

Both pictures depict the approaches of a (strange or known?) man; there

is an echo between fence and bench, the featureless clear, cold sky; both are

painted in a similar palette and with a similar touch; and yet one is clearly a

floating memory or fantasy, riding up in the air, while the other sits firmly

on a bench on the pavement, in the cold, clear present. The Front at Hove is

clearly a promenade on a British seaside already under decline. It’s a bright

day, but the aging holidaymakers are wrapped against the chill. Perhaps it is

off-season. The crowds have all gone home, possibly never to return.

If Summer Lightning is an obvious fantasy, there is a general feeling

in The Front of an all too real entropy and malaise, all the more poignant when

highlighted by the bracingly clear, cold-breezy daylight. And yet the row of

buildings ripple and eddy like a cartoon dream sequence, the right-hand side of

the picture occupies some kind of mental space, as if the woman’s thoughts are

drifting up and away. Perhaps we aren’t seeing a real row of hotels after all,

but a memory of some resort town in its glory days; perhaps we are merely in

some park in the city, with a pond over the rails. One could imagine the woman

on the bench remembering the Echo, or the Echo of Summer Lightning floating

somewhere above this scene as a dramatic counterpoint, or as an absent mise en

abyme within it. Or perhaps it’s a scene from a romantic novel she’s reading to

while away the hours, overlaying itself with her lived reality in this not

quite real place, this ghost town. Or is she (and Sickert) remembering at least

something of a real, lived past in the Echo? Was the world really more romantic

then, more alive, or were they merely younger? Does the memory cheat? Are these

threadbare fictions and guestrooms all we have left?

The silent onlookers of the curved row of buildings cannot help but

recall Sickert’s paintings of theatre balconies with their swirling, abstract

arabesques- but the lights and the greasepaint have faded, the show is still

going on but no one is watching, it's all been seen before. Our characters are

left alone in the cold blue shadows of the sun. They sit huddled in one corner-

we are already looking away, perhaps in embarrassment. The world moves on.

It’s worth reiterating that the two pictures have remarkably similar

subjects and are ostensibly painted in a similar manner, with their dominant,

chalky, dry-rubbed sky. And yet they have totally different registers, due only

to the very slight shifts and stresses that separate them. Hung side-by-side we

know one is ‘real’ and one is not. And yet, we also know, both are somehow

‘true’, authoritative.

.

The re-framing of clichés as something ‘true’ (in fact, the only

‘truths’ we may possess) would be a recurring motif in the work of Samuel Beckett.

Certainly, many of Beckett’s plays would consciously mirror the set-ups and

scenarios of music hall and popular theatre- re-imagining and re-framing the

tropes of the popular form in such a way as to tease out their existential

potential, inhabiting a given language while simultaneously using and

critiquing that language. Happy Days, with its estranged, end-of-the-pier routines

and props, is especially close to the Echoes, with Beckett asking that the set

incorporate a ‘pompier trompe-l’oeil backcloth to represent unbroken plain and

sky receding to meet in far distance’, characterised by ‘a pathetic

unsuccessful realism, the kind of tawdriness you get in 3rd rate

musical or pantomime...laughably earnest bad imitation.’ While this kind of

intentionally bad fakery and bad taste was pretty well established by the time Happy

Days was written and staged 1961, it was pretty much off the program for

serious painting in the 1920’s-30’s (Picabia’s work in the 30’s-40’s, for

example, was practically laughed off as an embarrassment at the time. And while

Sickert’s Echoes are not intentionally ‘bad’, they do pull their own

illusionism way up short while, seemingly knowingly, pushing acceptable taste

to its limits).

The default setting of late 19th-early 20th

century art, even at its most progressive, was to take the picture as something

more or less directly related to observable or imaginable phenomena or

condition of being, an extrapolation from the perceivable world, no matter how

exaggerated, expressionistic or abstracted. From impressionism through cubism

the picture always registers as a series of experiments and findings as a

reaction to the world, and the problems and implications of representing it,

broadly. Similarly, its form of address is- broadly- direct, serious.

Yet there are a few painters throughout that period working within a

slightly different agenda- painters whose work registers much more emphatically

as experiments and findings as a reaction to pictures themselves, and the

implications and problems of representation within the form (1930's Derain being a prime example).

Indeed, the fallout from post-impressionism, and from early cubism,

Fauvism etc., was to some extent a series of attempts at bringing ‘the picture’-

the composed, potentially meaningful image- back into progressive painting, many

painters having a kind of ‘anxiety of classicism’, making pictures that

re-embraced or tried to wrestle with the Old Masters: once the new visual

languages had been established there was a move to measure themselves against

the achievements of the past.

Thus the period beginning full-swing modernism is characterized by

certain alternating anxieties and arrogances about what painting should be-

perceptual or pictorial, subjective or objective, window or object- and the big

names of the cannon are often justly there because they played off these

paradoxes, sometimes leaning more one way or the other.

We tend to think of Cezanne, for

example, in more perceptual than pictorial terms. Yes, a Cezanne internalizes a

tradition, it rejects or expands upon this or that tangent of existing art, and

yes it pivots between being a field our gaze enters into and a thing it falls

upon- but we don’t feel that should be the point, rather we should check and

measure the picture against the world of things and places, our

perceptual-sensual responses to them, and not the world of pictures, primarily.

That’s the case in the landscapes and most of the still lives and portraits

anyway- but then there are the bathers, which refer to a tradition of

‘invented’, blatantly synthetic images, to a world that pretty much only exists

in pictures, an inherited image world, or even the card players which refer to

an existing ‘painting’ motif, a clichéd motif which is in a way so familiar

that it reads as a neutral ‘excuse’ for formal experimentation (significantly

there is also the portrait of his son dressed as the harlequin- the frequent

appearance of the clown or Pierrot throughout the period perhaps reveals

something of this anxiety- the performative, role playing, self-conscious

aspects of art - so much so that it’s become a cliché of artists’

self-presentation, a through line from Goya, Watteau, Daumier, Picasso, Derain,

and so on to Sinatra and Bowie).

And further, if Cezanne works between the perceptual and the pictorial,

the results still come across as essentially views we might look on- either

more or less synthetic and artificial but still authoritatively presented under

their own logic, optically transcribed rather than ‘made-up’ constructions and

inventions. Sickert’s Echoes come from a tradition that is emphatically not trying

to work within such an optic-perceptual form of address, but from a tradition

of pictures that blatantly address themselves as invented images, drawn/painted

characters in a scenario.

One of the most singular figures in this respect is Daumier: at the

height of official salon academism, his works take on a quality of something

much more consciously pictured- pictured and painted. Their dominant note or

register, their form of address, is as emphatically and consciously ‘painted-pictures’.

He’s not even like, say, Degas, with a range of chosen subjects and

motifs culled from daily life, but rather takes images or motifs that have a

kind of precedence or type (even if very distantly, or allegorically from old

religious painting, or he makes it seem like the images have a precedence, are already a 'type'), as if he’s already painting pictures of pictures, always

just one step further away from a real world and into a world of pictures (and

not the straightforward world of symbolism, but a world of pictures that are

pertinent to the artform painting, or which give themselves to the form). The

Quixotes, the street performers, the mother and infants/laundresses, are all

like transformed academy pictures, where most of the supporting characters have

been cleared away, the light failing, the paint and forms dispersing or

metamorphosing as we look, honed, whittled and essentialized- in fact, rather

like echoes- they carry a sense of archetype while never actually being

straightforwardly ‘typical’. There is always one stage of removal, both from a

common painting language and from an observable reality- while the image

remains potent and present due to the strength of composition and the

physicality of the paint. They find the emblematic, charged, mythic or poetic

image within the everyday, and within the very notion of ‘picturing’.

Often it’s very clear the images have been arrived at through the

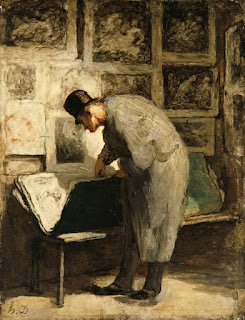

process of painting (Man on a Rope (4., 5.), the Laundresses- though later he’ll perhaps fake this

effect with carefully rehearsed strokes in Woman with a Child in Her Arms or Pierrot with Mandolin (6., 7.)), that their raison d'être is painting and that the condition

of their making is painting, and that the way of seeing they are critiquing is

painting’s ways and means of seeing. It’s not an optically motivated art, but

an image (specifically a painted image) motivated art (though, of course,

Daumier is not limited to studied self-criticism- the subjects are definitely

the ‘subject’ of the paintings, in all their thematic breadth and depth).

|

| 5. |

|

| 6. |

|

| 7. |

To put it very crudely, if Cezanne is by and large interested in

painting an apple, Daumier is interested in the painting of an apple. It’s not

always a clearly delineated difference (part of why Matisse is such a perennially

fascinating figure is the way he’s often highly invested in both registers),

more of a sliding-scale. Perhaps we can imagine it as being at either a closer

distance to or at a cooler remove from that which is painted: the main roster

of impressionists up-close to the canvas surface, reproducing perceived lighting

effects yet detached from the subject or image, Cezanne flitting intently between

picture and object, while Degas stands back, arms folded, with his eye on the

whole frame, synthesizing from sketches and memory and re-structuring as a

‘picture’. Daumier is one step further back again, often critiquing the very

act of making and looking at pictures, the idea of ‘subjects’ (see his pictures

of connoisseurs leafing through prints, artists at easels, even the spear and

shield/palette and brush of the hopeless dreamer Quixote etc.- the very notion

of ‘Cezanne-ness’, of ‘Degas-ness’, of a looker-maker, of a ‘picturer’ is what

Daumier internalizes and often depicts, though it’s there even in subjects that

have nothing to do with the idea of ‘the artist’ at all, in the sheer indelible

forcefulness of his images).

Daumier is interested in the self-identity of images, and is far more

conscious of the activity of painting/picture making itself, while modernism on

a whole seems to take images and their construction more as a means to an end (again

though, there are some pretty great ‘in the studio’ Picassos from the 20’s/30’s

which more directly explore the act, and a Cezanne always implicitly registers

the act of looking-making). It’s essentially a question of attention- in what

ways the artist or viewer’s attention is directed towards or within or away

from the subject (the cliché of cubism being that the sheer difficulty of the

new formal language required an easy, neutral subject like a simple still life

so as to avoid any further thematic confusion or distraction. Though again,

this is to ignore the complexity of subject/form interplay, the real

possibilities and significances within cubist picturing of violin f-holes, vessels,

containers, solids, newsprint etc. I wouldn’t want to perpetuate the narrative

that subject or meaning were entirely absent or irrelevant for formal

modernism, rather that its relationship to subject matter is one of reduced

emphasis, a radical re-orientation of priorities from those of hierarchical subject-oriented

academicism).

If Degas is closer to Daumier

than, say, Cezanne, then Sickert- faithful pupil of Degas that he was-

ultimately has one foot firmly entrenched in the image-motivated school, much

more so even than Degas (seemingly confirming the theory that influence in some

ways skips a generation, his work often more closely resembles Daumier’s

provisionality and physicality. Similarly, Sickert began his career as

Whistler’s most devoted disciple and assistant, yet later rejected his master’s

reliance on optical effect and l’art pour l’art, empty aestheticism, in favour

of the charged or ambiguous image).

For all that Sickert was involved in draughtsmanship and observation,

he was also, fundamentally, knee-deep in the intermediate state of memory and

invention, and would go on to write that a painting should be ‘the singing of a

song by heart, and not the painful performance in public of a meritorious feat

of sight-reading’- just as Daumier, Manet and Degas would all reject plein air

for the picture laboratory of the studio.

For modernism, in general but particularly among its more programmatic

practitioners, one subject is as good or useful as another, the more neutral

the better- while for artists like Daumier and Sickert the notion of ‘subject’,

of what in the world to paint, is a driving problem. As Catherine Lampert notes

in the RA’s pretty great catalogue, ‘Daumier expresses a modern dilemma: when

the patronage and conventional subjects of Church and State fall away, and

excessive finish and sentiment are discredited, the open-ended possibilities

become daunting’. And if Daumier pretty

much operates in opposition to the Salon, Sickert has the unenviably complex

task of positioning himself throughout his career against British Whistler-ism,

conservative academicism, continental impressionism and radical post-impressionism,

fauvism, cubism, formalism- in subject matter as much as aesthetics.

The ‘Subject’ seems to have been something that haunted Daumier.

Rectangles are a recurring motif throughout his oeuvre- as if the world had

begun to present itself to him in framed portions. Or as if the picturable

world had begun to multiply, everything becoming available for aesthetic

consideration or cataloguing, disintegrating into a series of images (see his

picture of the artist in a kind of padded cell made up by canvas, window and numbered

construction lines(8.)). It’s the impulse that leads to the readymade, the

all-over, the serial or arbitrary- but Daumier and Sickert remain steadfastly

invested in the problems of selecting a subject and rallying a composition,

directing within the stage of the rectangle.

Daumier also seems to have been as very much alive to the

re-circulation and re-appropriation of images as Sickert would go on to be- Painter

Leafing through a Portfolio of Drawings (9.), for example, showing the artist as a

slightly comical, one-man-band collector, connoisseur, creator and rip-off

merchant, a balding scavenger with palette in one hand and drawing or print in

the other. Tilted canvas on easel, propped-up oil sketch and open portfolio

folder all seem on the verge of collapse, like the collapsible print display

easels he often paints- as if the images are tumbling out as much as they are

tumbling down, the picture itself a proto-cubist stack of cards (the definitive

study of Picasso’s internalization of Daumier is perhaps yet to be written).

Despite the ongoing debate around the extent to which we should take

the lack of ‘finish’ in Daumier’s work as being intentionally provisional, or

simply a matter of straightforward abandonment, there are countless signs that

he was keen to stress the activity of painting as pragmatic, un-romantic,

utilitarian, synthetic, anti-heroic, even bathetic (the ‘Quixote as Painter’

pictures are clear enough that painters, even the best of them, are delusional,

happily charging after their follies, constantly mistaking white blotches for

sheep, or attacking armies, or windmills on the horizon- though the viewer is

just as complicit in this folie à deux, or is perhaps the humouring, faithful Sancho Panza to the

painter’s Don). But, importantly, within that activity is still room for drama,

poignancy, complexity, poetry, foolhardy though it may be.

As his scores of popular lithographs skewer hypocrisy and pretension in

all their forms, its unsurprising that many should find the making and looking

at art as their targets: Landscape Artists- the first copies nature, the second

copies him (10.), is a witty illustration of the myth of ‘painting from nature’, unmediated realism etc., showing the chain of influence and image-consciousness described above,

with Daumier sitting happily at the back of the line, painting those in front. Paradoxically, Daumier and Sickert, great innovators that they are, show that there is nothing 'new' - under the sun, or indoors (except of course, there is).

We have little written evidence of Daumier’s position on art- not that

we should need it- most statements attributed to him coming later from the

reminiscences of friends and admirers. Cezanne claimed that the older artist

once told him, ‘I absolutely do not like Manet’s way of painting, but I find in

it this enormous quality: it takes us back to the figures on playing

cards’.

Quite what he meant by this is not entirely clear.

But it does suggest a championing of the archetype, the type, the allegory, the

strong image- the picture.

.

Many early modernists would go on to become preoccupied with this kind

of proto-postmodernist image consciousness/synthetic consciousness

(particularly late Derain, Helion and others), but Sickert was seemingly

already headed in that direction straight off the bat. Even his earliest mature

pictures from the first trip to Venice are synthetic, painting rather than

perceptually motivated pictures (see the almost Caufield, lurid pink and green

St. Marks’ (11.,12.), and compare them with Monet’s Rouen Cathedral series- Sickert's palette would be criticized as 'murky' throughout his career, yet it is surely an unprecedented and highly original achievement, strange invented harmonies that have nothing to do with the sun-drenched rainbows of continental painting of the period, nor really anything until very late in the 20th century). The Echoes

are a late, much, much more extreme version of this same impulse. They raise

similar questions to those raised by Daumier- about finish, about

provisionality, persuasiveness, perceived/relational/invented colour, the

by-turns concrete and phantasmagorical nature of painted images.

|

| 11. |

|

| 12. |

In fact, there are Daumier-isms peppered throughout Sickert’s career;

they both often leave construction lines visible, playing with the natural

‘authority’ given by such structures in spite of their signalling of

construction; they obscure or blot-out faces, sometimes, leaving figures as

types; they are drawn to high contrast lighting effects, often uglifying

up-lighting, and 3-part tonal constructions; both paint the world of the

theatre and its relationship with painting, Daumier arranging the composition

so that the spectators closeness to or distance from the stage is made ambiguous,

so that we cannot tell if the figures are watching actors on a stage in the

distance, or are huddled round a painted canvas, whether the flurried marks

denote spatial distance or merely denote flurried marks (13.,14.) ; similarly, Daumier’s Print

Collectors depict pictures within pictures, the closest thing to Sickert’s

Echoes, almost as if he’s zoomed in just that bit further than Daumier (15.); there

is a little remarked-upon Sickert of a dead hare strung up by the feet (16.), which

bears a striking resemblance to Daumier’s Man on a Rope, perhaps speaking of

energies taut, suspended and ultimately spent, muscle and weight, the balance and

gravity of fate and will; correlations of crumbling walls and crumbling paint...

etc.

|

| 13. |

|

| 14. |

|

| 15. |

|

| 16. |

Despite all this, Sickert was rather condescending about Daumier:

writing that he was a brilliant draughtsman, but that the paintings are nothing

more or less than ‘drawings in brown paint...they are merely superimposed’ (Sickert,

The Burlington Magazine, ‘French Painting’, 1924). In various letters and articles,

he stresses that Daumier is no great shakes as a painter, citing how easy it is

to ‘fake’ him as evidence of this deficiency. I doubt it was even a case of the

lady doth protest too much- Sickert was, for all the perceived ‘dullness’ of

his palette, an obsessional colourist, writing many, many formulas for mixing

up the perfect ground colour, for example. His essays and articles, lectures

and so on, are often at their snobbiest- not to say self-contradictory- on

matters chromatic (he placed Millet far above Daumier in the grand scheme of

things for this reason). But this is the area of biographers- he certainly made

no bones about how much he rated workaday illustrators like Gilbert, and the

symmetries with Daumier are there, should the artist approve or not.

-continued in part 2.