-continued from part 2

Sylvia Plimack Mangold’s most recent body of work perhaps skirts closest to boredom or misunderstanding, and one senses she is quite happy for that to be the case.

Her

paintings of trees risk coming off as the work of a painter playing it safe in

their dotage, yet they are bold and compelling in part precisely because of

this risk.

In

fact, they embrace and extend her earlier work- her interest in the array of

close tones in the leaves that fill the frame, for example, stretches all the

way back to the play of close tones in her stained floorboards from the late

1960’s. Indeed, Mangold sticks to her guns- the tree paintings absolutely

continue her investigation of intent observation vs. what I’ve termed de-centred

‘ambience’.

It’s

an odd combination which is at once very 1970’s (again, with some ties to dead

pan photography), but which also has precedent in two very singular painters

working in the latter 18th century- Francis Towne and Thomas Jones.

<<<<<<

The

Welsh painter Thomas Jones had a modestly successful career for a time,

painting conventional landscapes in the style of his tutor Richard Wilson, yet

his reputation grew exponentially in the 20th century when small

studies from his (six year) Italian painting trip were uncovered. Never

intended for public exhibition, the small works (mostly oil on primed paper)

are daringly progressive in their composition (they anticipate the effects of

snapshot photography and their assimilation into painting by decades). Painted

as Neo-Classicism was just segueing into Romanticism, they anticipate many

artistic concerns of the next two centuries.

A

perennial subject of Jones’ in this period is a blank façade- whether viewed

daringly close to the ‘viewer’, as if from the window of a facing building, or

simply filling the frame. They play with grids of rectangles, with abstract

bands of wall and sky, with extreme cropping; they anticipate qualities in

minimalism, surrealism, the Barbizon school, the ‘accidental’ compositions of

Degas, even Baldessari’s Every building

on Sunset Strip.

And-

with their ‘flat’ subject, their large, practically (for the time) featureless

passages given the barest of contextualizing details, their disorientation of

scale and elevation- they deal with many of the subjects and strategies that

have continued through Mangold’s career.

There

is a distinctly de-centred quality to them, a sense that everything in the

picture is as much the subject, that the totality of the picture and its

conception of the world is the point, that all points of the picture are put

forward for our attention (in A Wall in

Naples, the three hanging rags recreate the elements of the composition in

microcosm) which aligns it with the modernity that would lead to Eno’s

objectively ambient composition. They bypass the picture-making conventions of

the day by essentially eliminating (moral, spiritual, narrative) interest. What

significance there is to be taken is only that which we can give, what we are

free to give (how we might unravel the metaphorical significance of the blank

windows, the weathered and ‘worked’ surfaces of the walls, for example). The

painting of Virgil’s tomb from the introduction to this text excludes all

reference to the place’s wider significance, and yet flips back on itself to find

a subject within the objective facts; that a tomb is an absence around which

the lives of the living go on turning; that the absence of death is experienced

almost as a presence, a negative presence; that there is an unknowable hole at

the centre of things; any or none of these things are explored in its curious

state of late noon sunshine, that hovers between matter-of-factness and

existential dread (Hitchcock’s Vertigo, also

objective-yet woozy, has this atmosphere). It’s the same

kind of reflexive selection-by-rejection approach to ‘meaning’ and significance

that goes on in Mangold’s work- whereby an empty floor becomes something stared

at, and, like the painting itself, is a helpfully ‘quiet’ screen on which to

project.

If

Jones is ‘ambient’, by any stretch, it’s the more uneasy ambiance of Eno’s

later Ambient 4: On Land- in which he

explored a deep bed of dissonance and disturbance below the pastoral prettiness

of the surface. Mangold certainly tends to keep the darker thoughts in the

distance, but they are there if you go looking (certainly there are further

implications to the obsessively clean floors, the compulsive taping and

measuring.)

Returning

to the introduction, our other painter is a less radical yet still interesting

figure. Francis Towne, unlike Jones, does choose to include incidental

‘interest’ in his picture of the tomb- particularly the small figures of the

tourists. Yet they remain distant, dwarfed by the surroundings. What’s perhaps

more startling is the visual style- graphic to the point of being

illustrational in a very 20th century way. Indeed, though he was

relatively well-known in his time, Towne was rejected by the Royal Academy 11

times, was neglected for many years after his death, and was only ‘rediscovered’

by Paul Oppé in 1916, when claims were made about his having anticipating the

‘flatness’ and abstraction of the day.

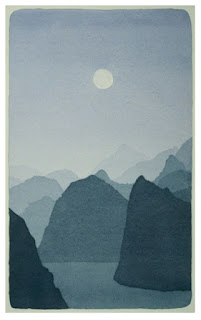

There’s

ultimately little ‘meaning’ in Towne’s work- trained as a decorative coach

painter, he often seems to be invested purely in pleasure and elegance as ends

in themselves. They speak neither of intellectualism (classical ruins are just

there, and pretty, rather than having any grander significance about the rise

and fall of civilisations), nor do they really have any proto-romantic

moodiness or emotional sweep. Rather, they have the same kind of blank, melancholic

stillness of Peter Schmidt’s holiday watercolours- the peculiar objectivity of

being within and floating outside of the world, the sense of travel through it

providing moments of tranquil beauty, if not any greater sense of perspective.

Perhaps

he was a great stylist in search of something more- or perhaps there was a

consciousness on his part that the world just often is, and that there’s something to be said for merely putting a

frame around it.

The

‘look’ of Towne’s watercolours is also extremely 1970’s- they almost recall the

fine-line artwork in the bandes dessinées comic books of artists like

Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, or the prog-rock album covers of Roger Dean (though

these examples lean more to the fantastical). Across Towne’s pictures are the

same kinds of mood and atmosphere as we’ve seen in Mangold, Schmidt, Jones

etc.- of looking out one’s room in the late noon, the early morning, the early

evening; times of possibility, action or inaction, between waking and

day-dreaming, passing the time. A sharp kind of lucid haziness.

Sylvia

Mangold has always maintained a practice of making watercolours, yet the tree

paintings in oil go some way towards having a kind of watercolour ‘look’, with

their lightness and luminosity, their (well-hidden but crucial) provisionality.

As

much as it carries the notion of dilettantism, watercolour also has

associations with other kinds of non-art image making. Mangold’s work also has

connotations of 18th century landscape painting in which the

activity was somewhat just as much aligned with

pseudo-archaeological/topographical practices of recording and rendering as it

was with notions of art or expression (Mangold’s trees include tiny notes of

month and time of day- 08’, 5pm etc.). This kind of empirical aesthetic, of

pseudo-scientific/mathematic fact-gathering, is also in the patterns of tiles,

the rulers and tapes, but always with the further philosophical implications of

trying to get at the structure of things, the philosophical implications of

measuring, squaring up, of horizons and vanishing points (obvious ancestors to

her trees are Cezanne, a very formative influence, and Mondrian).

There

is something in the fusion of lightness and precision in her trees that just

feels like 18th century tree studies. Never falling back on a

convenient shorthand for ‘leaf, ‘branch’, ‘foliage’ they are quite hauntingly

rendered in their totality and diversity.

The

trees feel animated in the way that Towne’s watercolours can also look like

stills from animation. There’s a sense in Towne’s flatness of shifting masses

of colour, of interlocking units of light and shadow, that our understanding of

the world is partial, that as grounded as everything can seem it can just as

easily shift and reconfigure itself like a passing cloud (perhaps this is where

the ‘meaning’ in his work is to be found).

There

is something analytic to both Mangold and Towne, a sense that they are at a

slight remove, trying to get at things and coming up against flatness, the look

of things. Yet for Mangold it’s not a simple process of showing this flatness,

but an attempt to reconcile it with our sense of volume, height, our position

on the ground, our capacity or incapacity for processing complex systems and

details and their relation to greater structures, zoom with wide angle (which

is in turn our position towards the flat canvas).

Still

pretty much ‘easel painting’ in their physical size, they have a grand sense of

scale. Mangold varies the level of cropping into (pretty much) three groups-

top half of tree (more or less sparse, particularly in winter), high mid-point

of tree with confusion of branches and foliage, and close-up of leaves filling

the canvas.

They

often disguise how odd they can be. The group that looks more to the top of the

tree are not in extreme perspective, as if from our position on the ground, but

generate through their cropping the feeling of looking up (she has said she

wants the painting to ‘whoosh up’) yet never being able to take in the whole

thing. Painted from life on the ground, there is an imaginary leap up to the

thick of the treetops. Mangold says ‘going to look HERE’- and we’re there. Like

the floors they are samples, samples of our feeling of what tree-ness is,

looped and reverberated. They internalize our sense of specific height,

gravity, opacity and transparency- all the things that add up to our sense of

trees as things.

And,

similarly to the floors, the trees are a discreet subject. Or they are made

discreet by their ambient composition, the way they fill the frame (they bring

to mind Constable sky studies). They are easy to pass by on a gallery wall- yet

they combine cumulatively to something meditative, something powerfully open

and committed, and strangely timeless (Mangold is 80).

The pictures mistrust, yet

co-opt, the very idea of edges and limits. For Mangold, the knowability of the

world is not to be measured out in rulers, but encountered as a centreless mass

of interacting data (Hume’s ‘bundle of perceptions’) of which we are part and

with which we must also, necessarily, interact. The world always spills over

her edges, in paintings which assert their own limits while vaulting over them.

Even within the picture there is

still a sense of incompleteness the longer one looks at them, despite their

seeming very much finished on initial viewing. The trees are discreetly

artificial, abstracted, all the more discreet because they seem so convincingly

observed, objectively composed. The amount of air, un-fussiness, fussiness,

busyness, un-busyness, simplification, complexification etc. in them is always

surprising, always well hidden.

In these pictures of dense foliage

or intersecting branches, she again comes back to that 70’s ambient approach towards

interest/attention. Dense and yet dispersed, they skirt the edges of boredom

while never becoming boring. One’s attention gets caught up in the slight

shifts and angles (which avoid the mildly hectoring tone of Cezanne, who

constantly asserts that this is what

should be happening with one’s attention), a ‘looking’ that is capable of being

intent while looping, floating, drifting. There is an ebb and flow of

attention, a mark or hue changes its role or function across the play of the

image- a shadow here becomes a recession there, a gathered ridge of white paint

defines both the edge of a branch and the light poking through- in the way that

ambient tape loops phase shift, with the eye/ear flexing from one focus to the

other. What is foreground or background shifts, what is surface, subject,

melody, support; what is happening in the object and what is happening to one’s

‘mood’...

In the tree pictures Mangold

fills the frame with an over-profusion of detail. While minimalism in the

visual arts was very literally about making minimal gestures and objects, what

was termed ‘minimalism’ within music was often about intricate profusion, dizzying

repetition and layering as a result of simple compositional procedures and

systems (as we’ve noted before, it’s Mangold’s inputs and variables which are

‘minimal’, not necessarily her results).

Mangold’s simple setup- paint the

tree, fill the picture with the tree- is made complex in the doing, having to

paint from life, having to be receptive and reactive rather than rationally

dictatorial (a mode of receptivity that carries through for the viewer).

When Pauline Oliveros was

criticised in the music press for apparently failing to ‘compose’ her pieces,

it was to miss that she was part of a radical reassessment of what it might

mean to ‘compose’ at all- to be a composer rather than an initiator, a reactor,

an improvisor. A suggester. As she explained-

The design of how [the electronic

pieces] would come into existence was what I mapped, not the content at

all...It was a kind of performance architecture using tape machines and

understanding certain operations in the circuitry which was non-linear...I

didn’t have time to think about it in rational terms, but had to act in the

moment.

For Mangold this is most evident

in the tree paintings, her most overtly ‘painterly’ works, in which she is reactive

to the haptic, the material, the physical things taking place within her

‘performance architecture’. She is alive to the shifting network of relations

between the sub and superstructure of her pictures, hardwired into the

circuitry of physical-material creative decision making (and so it’s a

different kind of ‘composing’). It’s

not so much that she’s painting from life that is unique- of course- more that

she’s applying that technique to something all-encompassing, to the demanding

structure of working right to the edges of the canvas without ending up

inelegantly incomprehensible, that the picture doesn’t end up in visual din,

that it remains ‘quiet’ but still absorbing, that it doesn’t suffocate. That

she is ‘alive’ in this situation comes through in the picture and for the

viewer, whose receptivity is similarly engaged (and who follows Mangold as the

structure of the tree/picture emerges).

It’s not the old hierarchy of

composer-performer-audience (which Eno has said he wanted to dismantle), but a

more flattened structure (or ecology) of co-exploration, in which the viewer’s

attention and receptivity towards minimal, subtle, infinitely and

infinitesimally variable differences within and between the works must

necessarily mirror that of the maker. When such an approach works, or is made

to resolve itself, both artist and audience are equally and pleasantly

surprised and delighted by the results.

IIIII

With these notions of suggestion

rather than assertion, of the flattened hierarchies of author and audience, I

shall hold off making any final remarks. Instead please find the following set

of open-ended instructions/suggestions from Eno and Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies deck- perhaps

they will provide further means of approaching the oblique pictorial strategies

employed by the ambient painter/re-shuffler Sylvia Plimack Mangold:

Define an area as 'safe' and use it as

an anchor

Ask your body

Do nothing for as long as possible

Don't be frightened of cliches

Go slowly all the way round the

outside

Is it finished?

Honour

thy error as a hidden intention

Don't stress one thing more than

another

Simple subtraction

Do something boring

Infinitesimal gradations

Make a blank valuable by putting it in

an exquisite frame

Don't be frightened to display your

talents

Make an exhaustive list of everything

you might do and do the last thing on the list

Repetition is a form of change

Idiot glee (?)

Question the heroic approach

Use fewer notes

Don't be afraid of things because they're easy to do

The tape is now the music

Convert a melodic element into a

rhythmic element

Feed the recording back out of the medium

Trust in the you of now

Give the game away

What is the reality of the situation?

Don't stress *on* thing more than another

In total darkness, or in a very large

room, very quietly

Fill every beat with something

Don't be frightened to display your

talents

Work at a different speed

From nothing to more than nothing

Go outside. Shut the door.

...